The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

ALAY HAN

The Alay Han occupies a unique place among the Seljuk hans, due to its courtyard mosque, the size of its covered section and the layout of its courtyard. Especially interesting are the courtyard bath and mosque and the independent building located to the south. The Alay Han boasts a unique figure unseen elsewhere in Anatolia: a single-headed, two-bodied lion. It also includes the earliest surviving portal with a muqarnas hood on a han portal. The decorative drama of the portal, with its vibrant red stones, grabs your attention from miles down the road.

|

The Alay Han prior to the 2008-9 restoration Eravşar, 2017. p. 23; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

The Alay Han prior to restoration, showing the vibrant red color of the stones Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.2, p. 69 |

|

|

|

carved lions on the portal |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 310; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 313; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 318; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Bilici, vol. 1 p. 87 |

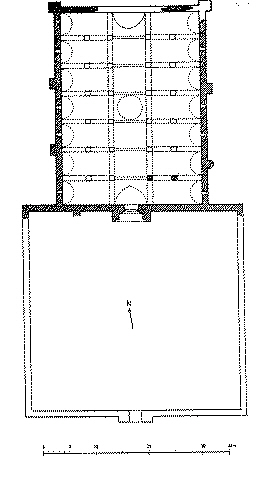

plan drawn by Erdmann |

the ruined courtyard Eravşar, 2017. p. 318; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 319; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 319; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Bilici, v. 1, p. 88 |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 321; photo I. Dıvarcı |

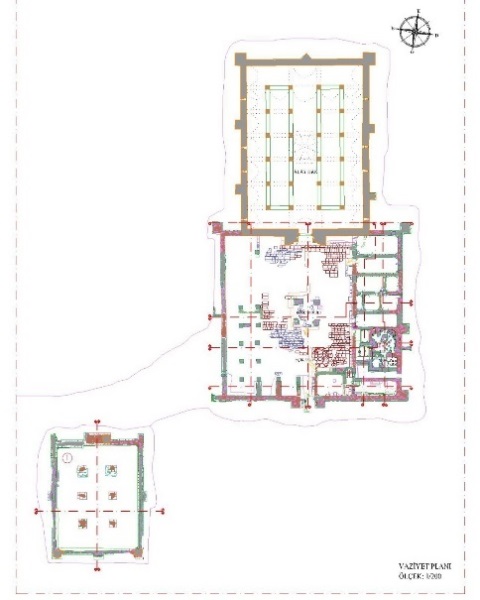

plan of courtyard service areas and the out building, drawn during the excavations of 2008. |

The double-headed lion of the Alay Han has been adopted as the logo of the Aksaray Township |

Bilici, v. 1, p. 89 |

DISTRICT

68 AKSARAY

LOCATION

38.518611, 34.354444

The

Alay Han is located 35 km northeast of Aksaray on the Nevşehir

road. It was once straddled both sides of the road, but now only the north

section remains.

It is situated at the crossroads of several caravan routes

which connect Kayseri, Niğde and Aksaray. This road was heavily trafficked

during the Roman, Byzantine and Seljuk periods. Until 2005, the Aksaray-Nevşehir highway passed in front of the han

over the courtyard section, but it has been diverted to

a more southerly location. Several important Seljuk settlements, such as Kaleköy,

Mamasin, Ortakoy and Ihlara, were located along this road.

For those traveling from Aksaray to Kayseri and Nevşehir there were two stations before the Alay Han: the Oresin Han and the Ağzikara Han. The next station is the Doğala Han, which is 30 km away. The Avanos Sari Han is located on the other side of the Kizilirmak River. The close proximity of these hans could have been due to the heavy commercial activity of the region.

OTHER NAMES

This han is not mentioned in historical sources by name, which is

hard to imagine in view of its size and importance. This has led many

researchers to postulate that the two hans mentioned in written sources, the Kılıçarslan II Kervansaray

and the Pervane Han, counl in fact be referring to this han.

Indeed, this building may be the one referred to in written Seljuk sources as the Kılıçarslan II Kervansaray. Originally called "Sultanhan", it is believed that its present name was given to avoid confusion with later buildings with the same name. Seljuk archives and Ibni Bibi mention another han, the Pervane Han.

The name Alai means supreme or grand, and it has also been suggested that since this han is the largest one in the region, it was named accordingly, but in truth, the exact origin of the name is not known. Erdmann associated the name of the han with Sultan Alaeddin Keykubad. He claims the Sultan could have named the han in reference to himself, as he did for the city of Alaiye (current day Alanya).

The surrounding village that was established after the construction of the han took its name from the han.

DATE

1155-1192

Not only is the name of this han mysterious, but also is its patron and date of construction.

INSCRIPTION

The inscription plaque over the crown door is for the most part ruined. The inscription is undecipherable for the most part and only a small section of it can be read. As such, there is no exact information relative to the patron and the construction date of this han. However, this han has traditionally been considered to be the oldest han built in Anatolia by the Seljuks of Rum.

Construction is thought to have taken place before 1190 based on stylistic analysis of the decoration, and certainly if the name of the Kiliçarslan Han (reign of İzzeddin Kiliçarslan II: 1155-1192), mentioned in Seljuk sources, does indeed refer to this han. This is the generally accepted construction date.

According to the legible section of the inscription, the han was built by a master workman from Ahlat: Tutbeg bin Bahram al-Khilati ("from Ahlat"). The inscription ends with a word which is most likely "al-najjar" ("woodworker"). Tutbeg was an itinerant master builder and woodworker who also was responsible for the construction of the muqarnas portal of the magnificent Sitte Melik tomb (1196-7) of the Ruler Shahinshah of the Mengucukid ruler of Divriği, located some 450 km away. These two examples show the mobility of craftsmen of the era. This architect brought the Ahlat's tradition of the fine stone craftsmanship to the service of at least two of Anatolia's twelfth century dynasties, and shows the importance of the mobility of artisans at this time. Through his two known works, the Alay Han and the Sitte Melik tomb, Tutbeg emerges as a pioneer architect in the late 12th century Anatolia, responsible for the earliest extant examples of the fine muqarnas stone portals which would become the landmark of Seljuk public buildings from the early 13th century onwards. Another possibility is that this wood worker could also have been Master El-Hac Mengümberti el-Hilati, who built the famous pulpit of the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya.

It is not certain if this han was a royal commission, but it would be logical to think that it was in view of its size and decoration. Erdmann, basing his assessment on the building material, construction techniques and superior craftsmanship seen in this han, claims that it could have been built in the first or second decade of the 13th century. The application of muqarnas to a crown door is reserved mostly for sultan hans. This han displays similar ornamentation with the first of the sultan hans, the Evdir Han, which was built by Izzeddin Keykavus I between the years 1215 and 1229. The ornamentation of the crown doors of the Divriği Kale Mosque, dated 1189, and the Kayseri Çifte Medrese, dated in 1202, are comparable to the decorations seen on the Alay Han. Thus, in view of the design, construction materials, workmanship and building techniques of the Alay Han, it can be seen that it shares common features with other Seljuk buildings dating from the beginning of 13th century, making it potentially the earliest sultan han built in Anatolia.

REIGN OF

Scholars are undecided: Kiliç Aslan II, Gıyaseddin Keyhüsrev I or

İzzeddin Kiliçarslan II (1155-1192)

PATRON

Again, it is not certain if this was a royal commission, and by what sultan.

Various hypotheses have been advanced on the patron of this han. Some researchers claim, without evidence, that the building dates from the reign of Kiliçarslan II and it is the Kiliçarslan II Caravanserai mentioned in Seljuk historical sources, and that it could have been a royal commission (sultan) han. Although Aslanapa believes this han to be a royal commission, there is no definite proof for this.

Another theory postulates that the han was built during the time of Alaeddin Keykubad. This han could very well be the Pervane Han mentioned in the journal of İbni Bibi. However, the han mentioned in his journal could have been one of the many other hans along this road, which was frequently traveled by Alaeddin Keykubad on his journeys from Kayseri to Aksaray and where he often stayed overnight.

BUILDING TYPE

Covered with open courtyard (COC)

Covered section smaller than courtyard

Covered section with a central aisle and two aisles on each side running

perpendicular to the back wall

7 bays of vaults

DESCRIPTION

The diversion of the modern road which ran in front of the han has allowed excavation work to be undertaken in and around the Alay Han in 2008 and the plan of the building was revealed.

The Alay Han is classified among the group of hans with a covered section used for lodging and an open courtyard lined with service areas. Although it is one of the oldest hans known, it already bears nearly all the distinctive architectural features of the 13th century sultan han group. The portal, surmounted by a muqarnas niche, the courtyard with covered section plan, the oculus in the central dome, the central vault, and the seven vaults on either side are typical of classical Seljuk han architecture.

The Alay Han is oriented north-south on a mountainside, with its lowest part to the south. It lies perpendicular to the road Entry is via a crown door in the center of the southern façade which leads into the courtyard. The crown door of the covered section is smaller than that of the courtyard. Both crown doors are on the same axis.

Unfortunately, the open courtyard section of this han has been completely destroyed, leaving only part of the covered section consisting of three bays roofed by seven vaults. Much of the plan was uncovered during the excavation project.

Courtyard:

The most exciting part of the excavation project of 2008-9 was the revelation of the layout of the courtyard of this extensive han. The former modern road literally ran through the courtyard, but once it was diverted, it became possible to excavate the courtyard. The courtyard, which had long been buried below ground level, was uncovered during the excavation work that was undertaken before the renovation project. The open courtyard section is oriented longitudinally in the north-south direction. The crown door, located in the center of the south side, is completely ruined. The presence of niches over the bearing wall on the west side of the courtyard indicates that there were probably other iwans in the courtyard. The two iwan niches protruding towards the interior of the courtyard are similar to the iwan niches in the Ağzikara Han.

The square piers of the two supporting lines on the west side of the courtyard were revealed, four in the first line and five in the second. There is a gap at the foundation level of the arcade that faces the courtyard and which is at a lower level than the courtyard. It is believed this gap was a trough used to dispose of animal waste.

Service areas and special rooms for lodging are located in the eastern wing of the courtyard, most notably the bath. The remains of a very large hamam are in front of the han and restoration work is continuing there. Most interesting are the foundation level water pipes and drain channels leading to the south side of the first room. This room is accessed through a narrow corridor. The bath section of the han is located next to a rectangular room, and its layout recalls that of the baths of the Kayseri Sultan and the Karatay Hans. A small room is located at the entrance to the bath, and was probably the dressing room. A small door gives access to a square room with a dome, which served as the warm room (tepidarium) and includes an entrance to the following room, the caldarium. The hot room (caldarium) section is very wide and square. The foundation paving stones were removed during the restoration, making it possible to view the hot water furnace and the stones of the piers carrying the paving. Two additional square rooms are located next to each other in the southern section of the caldarium. The existence of a furnace under these rooms indicates that these areas were used as private bathing rooms, perhaps like a modern-day sauna. An oblique L-shaped room surrounds the area to the south of the tepidarium and the caldarium. This room connects to the bath at the furnace level and is thought to have been a part of the furnace as well, and would have originally included a water tank behind it. The water pipes inside the walls, the fountain slabs and basins were also revealed during the excavation.

The first room to the north of the bath is rectangular and is entered from the

courtyard. The adjoining section consists of differently planned rooms

internally connected to each other, an application seen in other hans such as

the Karatay Han. The first room after the entrance is rectangular and the traces

of two doors have been found in the western side of the rectangular room. One of

the two rooms, entered through these doors, is long and narrow, and the other is

square. The square room gives access to yet another room. These rooms were

probably covered with a dome. These rooms must have been reserved for a

special use.

The last two rooms in the eastern section of the courtyard, located at the northernmost section, have the same plan and must also have been devoted to a specific use. A wide gutter between the crown door of the covered section and the wall of the east room, which continues along the wall surface of the covered section at 50 cm above the floor, was revealed during the excavation. This gutter perhaps served as the feeding and watering troughs for the animals.

This was a full-service han. Not only did this had include a bath, but the traces of a mosque in the courtyard were discovered during the excavations. The traces of four piers found during the excavations indicate that the area in the center of the courtyard was occupied by a stand alone kiosk mosque. The mosque was built on top of these piers, and a well located underneath the mosque was revealed during the excavation. Some of the water needed for the caravanserai was also supplied by this well.

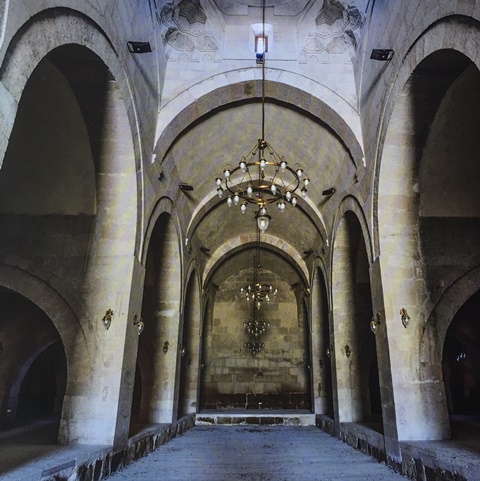

Covered section:

Behold the majesty of the crown door! The crown door of the covered section is situated in the middle of the southern side and projects from the main bearing wall. The crown door, with its very elaborate decorative program, carefully executed in a narrow area, presents a visual feast. The crown door complex is shaped around a pointed arch, surrounded with three borders. The outermost border is plain and the other two are decorated with different geometric elements. The edges of the borders of the second border were composed of regularly-spaced half square triangles followed by a row of half-star motifs. This motif can also be seen in the decorative program of other important buildings, such as the Ağzikara, Iğdir Ejder, and Aksaray Sultan Hans, as well as on the Divriği Site Melik Tomb. The border next to the half-star border is the widest one of the crown door, and is composed of geometric braids with eight-pointed polygons in the center. A composition composed of octagons surrounds the perimeter of the polygons. A double braid surrounds the perimeter with a double braid. This type of decoration is frequently seen in Seljuk buildings. The lower section of the crown door is a pointed arch. Two rosettes surrounded by spirals are set in the spandrels of the arch. The lower section of the arch contains five rows of muqarnas. The muqarnas hood of the Alay han is different than those of other Seljuk hans, which generally have 7 rows. The monumental scale and exquisite execution of the muqarnas cell hood here is impressive for such an early example. The vertical elements of the transverse flat arch rest on profiled lateral consoles, as is seen in the Ağzikara Han. The portal arch rests on lateral profiled consoles, which face to the interior of the door opening. The connection with the edges of the borders is provided in the corners by small pillars, which were reconstructed during the renovation. There is a line of naskh calligraphy and a damaged inscription above the row of muqarnas on the crown door. The placement of an inscription in this section is not a common treatment in Seljuk period buildings. There are additional differences: the han portal here differs from later portals, in that it does not have a cavetto (concave molding) frame, but rather a stepped recess with a patterned edge. It also differs because it does not have flanking niches. Rather, the Alay Han has a low-relief carving of a pair of affronted lions that share a single-forward looking head at the base of the muqarnas hood. The lions have two bodies but share a single head. They lean down inside a lotus flower on the inner face of the middle frame. The head faces forwards and the bodies, sitting on their hind legs, are drawn in profile. Their tails wrap over their backs. The origin of the sui generis single-headed, two bodied lion figure is not known. It was discovered during the restoration on the han carried out in 2008. This royal symbol is seen on the portals of the Cifte Medrese in Kayseri and in the Izzeddin Hospital in Sivas. The size of the lions is 0.45m x 0.23 m.

The covered section is composed of seven lateral aisles in the east-west direction, parallel to the rear wall. With its transept of seven naves placed perpendicularly to the central nave, it displays the same plan features as highly-programmed buildings, such as the Sultan Hans, which has led most researchers to believe this was a royal commission.

The covered section comprises a central nave with a nave on each side running the full length of it, reinforced by two support aisles. There are six square piers in each of side naves. The lateral aisles are covered with low pointed vaults. The vault in each aisle is backed with two square piers which connect to the central nave at a lower level. The support rows in the north-south direction bear the vault of the central nave, and are connected to each other by pointed arches in the same direction. The thinner surrounding arches over the aisles balance the load. The central nave in north-south direction is covered with a pointed vault at a higher level than the other naves. The ribbed arches carrying this vault run in the east-west direction and reinforce each other. A dome covers the area where the central nave intersects with the third and fourth support aisles. Squinches with four rows of muqarnas served as transition elements for the dome. Slit windows, situated in the main axis of each squinch, illuminate the inner part of the dome.

During the excavation, the loading platforms in the covered section of the han were also revealed. The section beginning at the arch piers on both sides of the central nave and continuing to the pier behind it was designed as a loading platform. The level of the platform is 40 cm higher than the ground level.

Lighting of the covered section was provided by slit windows opening in the first, third, fourth and sixth aisles of the side naves. In addition, four slit windows in the lantern dome over the middle of the central nave also provided light to the building.

EXTERIOR

The outer walls on the east and west were reinforced with support towers placed opposite each other. The northern corners of the building are reinforced with square towers, thicker than the others. The ruined northern wall was completely rebuilt during the restoration project.

BUILDING MATERIALS

The tufa stones used in the construction of the han were extracted from quarries located southeast of the caravan route. The old route and the quarries now lie under the modern asphalt road. The walls were built with smooth-faced stones using the rubble wall technique, with an infill of pebbles and mortar between two stones. Large-scale stone blocks were placed in the lower courses. Reuse spolia materials were found only in the rooms in the northeast corner of the courtyard. These consist of architrave stones from the Byzantine period. Some blocks display mason marks similar to those seen on stones in other Seljuk buildings; however, some marks were unique to this building.

Another feature distinguishes this han: the separate out-building which is located south of the han. Four corner walls of differing heights, belonging to a separate building south of the han, were discovered during the excavation and renovation of the Alay Han. It was divided into three naves with two support lines, each carried by three square piers. The main walls were constructed in the same fashion as those of the han, of tufa stone using the rubble wall technique. The walls are reinforced with square support towers in the corners and in the middle of each side except for the northern side. This independent building recalls those seen at the Kizilören Han and Kuru Han 2 on the Kayseri-Elbistan road. The purpose of this structure is not certain, but some have proposed that the outer buildings in these hans were ribats built for military purposes. In view of the metal utensils and tandir pit ovens found here, it could have served as a cookhouse.

A river flows through the hillsides to the north of the han. The traces of a water system found in its river bed indicate that it had been outfitted to supply water to the han.

DECORATION

As mentioned above, the portal of the covered section offers a stunning display

of decorative elements. It is framed by a broad border whose stonework

geometrical decoration of interlocking octagons and diagonal swastikas, along

with seven rows of muqarnas (stalactite carving) is unusual. The hall door

features a carved lion with a single head and double body, cut in low-relief.

The lion's face is frontal, and the bodies are facing each other in profile. The

tails of the the two lion bodies pass between their hind legs, wrap around the

side of their bodies and terminate above their backs. The portal is framed by a border decoration of running triangles. The ornament

on the portal door has stylistic similarities to the Great Mosque of Divriği

of 1180 and the

Çifte

Medrese in Kayseri of 1201.

The stone of this han has a distinctive red tone, which adds an innate

decorative element.

DIMENSIONS

2,900 m2 (total external area)

hall: 1030 m2 (28.50 x 41.50m)

courtyard: 1520m2 (41.50 x 39m)

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

The han was badly ruined and the courtyard section had totally collapsed. Only the portal remained, a proud vestige of the long architectural tradition that it inaugurated. Rott in 1908 published a photograph of the han and described the crown door as magnificent, and indicated that the stones of the han were taken away to be used for the construction of other buildings.

The crown door of the covered section and its wall, as well as the east and west walls, were the only original sections standing before the renovation in 2008. The han was repaired overall, its vaults restored and the walls rebuilt. The lantern dome of the central nave was reconstructed by the comparison technique. Some sections of the courtyard and the neighboring building were partly restored, but the restoration remains unfinished and its future plans are undetermined.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları, 2007, p. 452.

Altun, Ara. An Outline of Turkish Architecture in the Middle Ages, 1990, p. 198.

Aslanapa, Oktay. Turkish Art and Architecture. New York: Praeger, 1971, p. 147.

Bayrak, M. O. Türkiye Tarihi yerler kılavuzu, 1994, p. 571.

Bektaş, C. Selçuklu Kervansaraylari, Korumalari ve Kullanilmalari Üzerine Bir Öneri = A proposal regarding the Seljuk caravanserais, their protection and use, Istanbul, 1999, pp. 108-109

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 1, pp. 86-89.

Deniz, Bekir. Alay Han, Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı, 2007. pp. 51-75 (includes bibliography).

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, p. 23, pp. 310-321.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961, p. 80-83, n. 24; vol. 3, pp. 122-124.

Ertuğ, Ahmet. The Seljuks: A Journey through Anatolian Architecture, 1991, p. 78.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 479.

Gülyaz, Murat Etuğrul. "The Kervansarays of Cappadocia". Skylife Magazıne, December, 1999.

Hild, F. Das byzantinische Strassensystem in Kappadokien, 1977, p. 71.

Karpuz, H. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, vol. 1, p. 69.

Kiepert, R. Karte von Kleinasien, in 24 Blatt bearbeitet, 1902-1916.

Konyalı, İ. H. Abideleri ve Kitabeleriyle Niğde Aksaray Tarihi I, Istanbul, 1974.

Kuban, D. Selçuklu Cağinda Anadolu Sanati, 2002, p. 242.

McClary, Richard P. Rum Seljuq Architecture 1170-1220: The Patronage of Sultans. Edinburgh, 2016, pp. 63-64, 72.

Peacock, A.C.S. & Nur Yildiz, Sara, editors. The Seljuks of Anatolia, 2013, pp. 39-42; 56 (provides photo of the architect's inscription stone).

Oberhummer, R. & Zimmerer, H. Durch Syrien und Kleinasien, 1898. 1899, p. 252.

Ögel, S. Anadolu Selçuklarin Taş Tezyinati, 1966, p. 7.

Özergin, M. Kemal. Anadoluda Selçuklu Kervansarayları, Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 145, n. 6.

Özgüç, Tahsin and Akok, M. Alayhan, Öresunhan ve Hizirilyas Köşkü Iki Selçuklu Kervansarari ve Bir Köşkü. Belleten 21 (8), 1957, pp. 1-84.

Rice, Tamara Talbot. The Seljuks in Asia Minor, 1961, p. 206.

Rott, H. F. Kleinasien Denkmaler aus Psidien, Pamphylien, Kappadokien und Lykien, 1908, pp. 254-5.

|

rooms in the courtyard, perhaps belonging to tthe hamam |

start of the renovation project, 2009

|

|

|

|

|

the photos below show the han before its restoration in 2008-2012: |

|

|

View from road, 1994

|

Main portal with its elaborate stalactite vault, 1994

|

Photo by Erdmann (#114) |

Photo by Erdmann (#115) |

|

Photo by Erdmann (#117) |

Photo by Erdmann (#118) |

©2001-2025, Katharine Branning; All Rights Reserved.