The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

CAKALLI HAN

The only remaining Seljuk-era building in this era, this han with a curious name was built along a well-traveled road down from the Black Sea. Its damaged crown door was recently restored, thanks to a drawing left by an American missionary.

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 299; photo I. Dıvarcı |

han before 2013 renovation |

|

Karpuz Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.2, p. 274. |

han during the renovation... |

han after the renovation Eravşar, 2017. p. 305; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Bilici, vol. 3, pp. 225 |

|

detail of decorated stones, left side of portal |

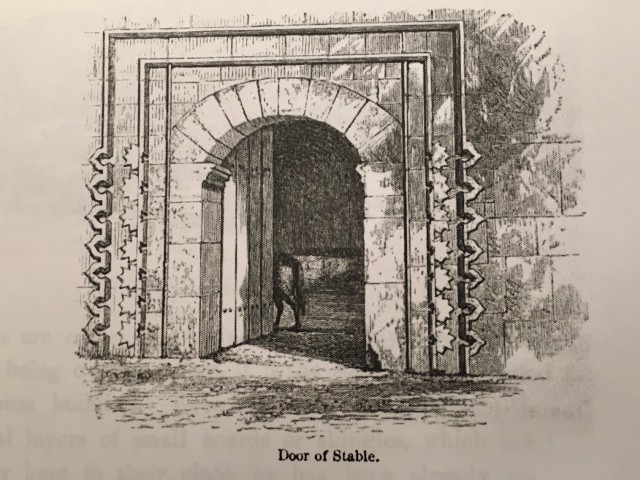

Sketch of the entry of the han by Henry Van Lennep; note the fine merlon detailing on the sides of the portal (see his sketch map of the region below) |

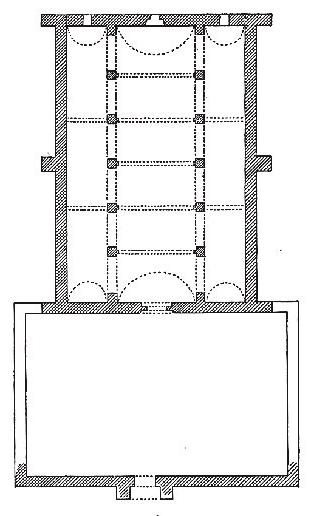

plan by Erdmann |

DISTRICT

55 SAMSUN

LOCATION

41.141361, 36.116052

The Çakalli Han is located off the Amasya-Samsun Road, 10 km northwest of Kavak near the village of Çakalli. It is approximately 35 km south of Samsun and 15 km northeast of Kavak. (Coming from Samsun, turn left at the restaurant "Unal Menemen Lokantasi" - and I would urge you to try some of their delicious memenen first, for the town of Çakalli is reputed to make the finest in Turkey - on the left, go down the small road past the abandoned primary school and gendarme post on the right, then take the dirt road to the right before the bridge and drive up about 50 feet; han will be on the right.) It was built near the Karatay Creek, a branch of the Mert River. A nearby two-arched bridge is named after the creek. The bridge has an inscription. This route leading south down the valley from Samsun has been in use since the Medieval Period until the end of the 19th century and had many hans along it, most of them dating from the Ottoman period. The American missionary Van Lennep indicates many of them on the map he drew in 1854. He states that "There are khans all along the route in this valley, which are much frequented by the mule drivers, the distance from Samsoon, and the cheapness of the feed being the chief attractions." During the Sivas governorship of Halil Rifat Pasha (1882-1885), the Samsun-Sivas Road was repaired and improved and many bridges were built along it, including the one next to the han. A small village is established near the han and a house was built adjoining the han. Below the han is an Ottoman-era bridge and the wooden Kasımzade Ahmed Sufi Cami ("Aşaği Mahalle Cami"), dated 1878.

OTHER NAMES

Taş Han (often called this by the locals, as are many other hans)

It is known that Çakalli Turkmen were settled in the region in the 17th century. Accordingly, the name of the han and the village must be related to this event.

The earliest information concerning the han is found in the Ottoman cadastral records of the 15th and 16th centuries (Öz, 1999). The han is called the Karbansaray-i Bergos in Ottoman records and it is said that it had a regular income from its sponsoring foundation.

Several travelers have visited the han, such as Tschihatscheff (1848), Mordtmann (1850), and the American missionary and artist Van Lennep (1854), who left a description in his travel journal (see complete entry below) and drew an accurate depiction of the main entry door, and Tozer (1881) who said the han was out of service. All called it the Chakal Han.

DATE

Estimated at 1237-1244; during the reign of Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II (d. 1246)

Although there is no inscription plaque indicating the construction date or the patron, it is generally assumed that this han dates from the mid 13th century). The han has the design and technical features of 13th century Seljuk buildings. The carved edging surrounding the door is similar to many other Seljuk buildings of the early 13th century. Other hans, such as the Kesikköprü, Paşa and Çekereksu Hans, have three naves in their covered sections like the Çakalli Han.

PATRON

Although not attributed to the group of seven hans traditionally considered as commissions of Mahperi Hatun (Pazar, Cimcimli, Çekereksu, Tahtoba, Ibipse, Çiftlik and Ezinepazar), it could possibly be considered as part of her program. Pervane Muineddin Süleyman is also considered a possible patron, and the architect may have been Gevherbaş ibn Abdullah.

INSCRIPTION

There is no inscription plaque, so an exact date and patron cannot be determined.

BUILDING TYPE

Covered section with an open courtyard (COC)

Covered sections smaller than the courtyard

Covered section with a central nave and 1 nave on each side running perpendicular to the rear wall

6 lines of support cross vaults parallel to the rear wall

DESCRIPTION

The han is on a north-south axis. The entrance faces south. The han was originally built with a covered section to the north and a courtyard with service areas in front of it to the south. The courtyard was lost over the years, but its traces were uncovered during the excavations. Erdmann spoke of a fountain that was attached to the han, but all traces of it have been lost.

Courtyard:

The courtyard area had collapsed completely, but traces of the foundations of the areas inside of it could still be seen. The courtyard was placed perpendicularly to the covered section, and is narrower than it. Some of the stones of the courtyard walls were used to build a retaining wall for the homeowner next door.

Again, the American missionary Van Lennep provided some clues to the original layout of the courtyard. He stated in his journal: It consists of a court with rooms on the right and left, and a large empty stable at the extremity. The doorway of the stable is handsome, and built in a style of architecture which denotes a considerable antiquity, possibly 700 years.... These service rooms seen by Van Lennep were buried over the years. Following the clear indications of Van Lennep, researchers set out to find them during an excavation before the restoration project in 2009. It was determined at this time that that the crown door of the courtyard was set on the same axis as the crown door of the covered section, and that the covered section and the courtyard service areas were built with different techniques and materials, perhaps indicating different construction phases. The traces of the eastern rooms mentioned by Van Lennep were discovered at this time and two wall sections lying parallel to each other were also found in the west. The five rooms on the eastern side are of different sizes, and each must have had its own door onto the courtyard. A square room was discovered at the northwest corner of the courtyard behind the two parallel walls, and this section could have been arcades.

Another traveler left a clue concerning the crown door, this time the one leading into the courtyard. Tozer, who had seen the building in 1879, said that the crown door of the courtyard was solid and had a pointed arched opening. During the excavation project, the location of this door was clearly discovered.

Covered section:

The covered section is divided into three naves with two support lines. it measures 29.20m in length. Six pointed arches sit on five piers in each of the support lines, and continue in the east-west direction to the rear wall. The arches in the north-south direction in the support lines are braced by an additional arch on the third and fifth lines. The middle nave is higher and wider than the side naves. (10m wide and 5m wide for the side naves).

Over the years, most of the stones of the arches were removed, but the traces on the vaults were still visible. During the restoration work, the demolished parts of the covered section were reconstituted with tufa stone. There is a small doorway leading into the covered section on the northern side of the front wall of the covered section, which was probably cut sometime after the 1950's.

Lighting of the interior space was provided by slit windows, one at the middle of each of the vault openings on the rear, north wall. In addition to these windows, there are also small embrasures on the sides, which could have been used for aeration and evacuating smoke and odors from the animals.

A loading platform, approximately 70 cm in height, was previously located in the middle nave, but became damaged over the years.

The crown door of the covered section faces the courtyard. It remained partially intact over the years due to the strength of the stones, although the upper part and the arches collapsed before the restoration. The door had been restored during the Ottoman era, and some marble pieces were installed at this time. The extremely precise drawing of Van Lennep was a precious aide for the refurbishing of this door during the renovation. The door is surrounded by two borders. The outer border is comprised of a vertical row of relief-carved pointed lappet elements, positioned on their sides with the points facing outwards. The second border comprises a vertical row of half eight-pointed stars carved in low relief, positioned horizontally. Above the crown door is a square framed space on the east side, which was possibly the location of the inscription plaque. Stone blocks were also used in the lower courses of the crown door and for the carved decorations on the borders. The rest of the crown door was made of flat blocks of tufa of a darker pink color. The reason why the same material was not used in the upper sections is not yet understood.

EXTERIOR

The exterior walls of the covered section are reinforced with four rectangular support towers, one on each long side and one in each corner of the north wall. In addition, there is one tower on each of the corners of the front south wall of the han.

BUILDING MATERIALS

The main construction material of the covered section is smooth-cut yellow tufa stone of substantially different sizes and quality.

DECORATION

The only decoration in the han is on the borders of the crown door. Each side of the hall door is decorated with a band of handsome pointed key motifs, a decor found on many Seljuk monuments. It is identical to the portal decoration on the nearby Burmali Mosque in nearby Amasya, dated 1237, which supports a similar date of construction for this han.

DIMENSIONS

Total Area: 1,300m2

Hall area: 570m2 (22 x 32.50m)

Courtyard area: 500m2 (31 x 20m)

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

This han was restored in the Ottoman era as this road was in commercial use up until the 17th century. A renovation of the building was made in 1650. The Seljuk trade route passed in front of the han and followed the Çakalli River, but during Ottoman times, this road was abandoned in favor of a road passing farther south. It was in service until the 1950s, at which time the arrival of trucking vehicles altered the routes taken for commerce. After this time, the han was used as a municipal storage garage for road equipment. Unfortunately, the upper section of the crown door was destroyed in 1964 in order to allow the trucks to enter the han. The courtyard crown door was also torn down at this time. A hole was dug inside the covered section for servicing the maintenance vehicles. After the han went out of service a few years later, the villagers who had settled around the han converted the building into animal pens, opened a door on the south side, placed a staircase on the front for climbing up to the roof and built a brick wall inside the nave on the west side.

In preparation for the repairs, excavation work was carried out in the covered section and in the courtyard under the supervision of the Samsun Museum in 2008. A restoration project for the han began in 2012 and was completed in August, 2013. During the restoration, the broken arch of the crown door was repaired, thanks to the drawing left by Van Lennep, and missing sections of the borders were completed to make a frame. The missing building elements of the main walls and the interior were reconstituted by using new building materials. The han is now open for visits and serves as a restaurant.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Bayraktar, M. Sami. Samsunda Anadolu Selçuklu ve Ilhanli Döneminden Kalan Tarihi Yapilar. Uluslararasi Sosyal Araştirmalar Dergisi, Vol. 2/7, Spring, 2009, pp. 85-118.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı : Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 3, pp. 224-225.

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 299-309.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961. Vol. 1, pp. 77-79, no. 22.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, pp. 484.

Karpuz, Haşim. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, vol. 2, p. 275.

Kiepert, R. Karte von Kleinasien, in 24 Blatt bearbeitet, 1902-1916.

Öz, M. XV.-XVI. Yüzyilarda Canik Sancaği. Ankara, 1999.

Özergin, M. Kemal. "Anadolu'da Selcuklu Kervansaraylari", Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 145, n. 16.

Rice, Tamara Talbot. The Seljuks in Asia Minor, 1961, p, 206.

Şahin, Mustafa Kemal. Geçmişten Geleceğe Samsun. Samsun: Samsun Belediyesi, 2006, pp. 427-447.

Tozer, H. F. Turkish Armenia and Eastern Asia Minor. London, 1881.

Van Lennep, H.J. Travels in Little-known Parts of Asia Minor. With Illustrations of Biblical Literature and Researches in Archaeology: Vol. 1. London, 1870, pp. 65-68.

Yavuz, A. T. Cakalli Han Restitutyon ve Restorasyon Raporu. Restitutyon Raporu. Ankara, 2009.

|

|

||||||||||||||||

The Cakalli Valley as seen from the han

|

||||||||||||||||

***

The American Protestant missionary Henry John Van Lennep, who was posted in Tokat from 1854-56, described his initial voyage down the Samsun road to Tokat in his journal, Travels in Little-Known Parts of Asia Minor. An accomplished artist, Van Lennep also included a fine sketch of the portal, as well as a detailed map. He captures well the beauty of this Pontic region and the ardors of the road at this time:

"...travelers generally follow an old paved road built some fifty years ago or more by a rich but wicked Turk, who hoped by this means to make the scales turn in his favor at the Judgment Day. The road passes along the edge of a precipice, and having never been repaired since it was made, the stones, which are large, have not only been worn smooth and slippery, but they have also been so displaced in many spots as to make a transit among them perilous in the extreme. We were, however, well rewarded for our perseverance when we made our exit on the other side, and all along our descent to Chakallu Khan, which lies six hours from Samsoon. Such beautiful fields, green hedges, fine fields of grain, and charming weeds, seemed altogether an anomaly in this part of the world. Our eyes could not cease to gaze upon the varied outlines, and the rich hues of the scenery, and we might have imagined ourselves among the charming hills, valleys, and hedgerows of old England, but for the tall and snow-capped mountains which occasionally peer in the horizon, and the complete absence of the neat and tasteful English cottage, and the harsh gutturals of the Koordish muleteers. And so we reached Chakallu Khan, the Jackal Han, which is really a collection of several hans built at different times. [note: the others were log cabin types of hostels built at a later date.] The oldest and original structure was of stone, and though somewhat in ruins, is yet inhabitable. It consists of a court with rooms on the right and left, and a large empty stable at the extremity. The doorway of the stable is handsome, and built in a style of architecture which denotes a considerable antiquity, possibly 700 years....The name of this place indicates that jackals are yet found in this neighborhood; but they are found no further inland."