The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

CARDAK HAN

Roaring lions greet you on the portal, and rare animal carvings can be seen inside this han, built by a patron from a politically-prominent family.

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 281; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Bilici, vol. 1, p. 356 |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 283; photo I. Dıvarcı |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

Inscription plaque (kitabesi) over main portal, showing the two lion's heads on each side |

.jpg) |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 285; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 285; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 282 |

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.2, p. 244 |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 285, photo I. Dıvarcı |

Covered section cells |

Fishes in relief on column capital in covered section |

Bull's head in relief on column capital in covered section |

plan drawn by Erdmann before the 2008 courtyard excavation |

Bilici, vol. 1, p. 356 |

DISTRICT

20 DENIZLI

LOCATION

37.828546, 29.665899

The Çardak Han is located 300m north of the Denizli-Dinar Road, 55 km east of Denizli, near the village of Çardak (the ancient Charax) on the northwestern edge of the lake known as the Aci Göl (to the left of the train tracks and near the Saray Cemetery). The old caravan route passed to the south of the han. This caravan road, which connects the Aegean Region to Central Anatolia, was used extensively throughout history. The ancient roman road from Ephesus to Pamphylia and the Byzantine road from Konya to Laodicea (Denizli) and Ephesus met near the han. The entrance to the han faces east and the han is linked to the main road by a by-road. This old caravan route was already in use in the Byzantine period, and led from Konya and Beyşehir to Eğirdir. The Çardak Han was a crucial check point (derbent) for controlling the passage between western and central Anatolia at the lookout point of a narrow pass between the mountains of Maymun and Söğüt. The Çardak Castle is located near the han. It changed hands several times in the 12th century between the Byzantines and the Seljuks. Formerly, the Byzantines built a castle fortress here as a lookout point. The spolia that was used in the construction of the Çardak han could have come from this Çardak Castle site.

The next han towards Denizli is the Ak Han. The previous han in the direction of Dinar is the Pinarbaşi Han. The Çardak Han was the westernmost caravanserai of the Seljuks until 1253 when the Akhan was built. This western group of hans are testimony to the engagement of the Seljuk elite to establish a presence in the frontier zone with Byzantium. It is believed that this group of frontier hans may also have plated a role as government outposts and in maintaining local security with the many nomadic Turkmen tribes who had settled there.

NAMES

Han Abat or Han-Abad. It is called Hanbat by the locals.

The Byzantines called the nearby castle the Charax castle, and the name Çardak may have derived from this, but Erdmann claims that it is derived from a name which signifies a cover with four layers. The han was visited by several 19th century voyagers to the region, including Arundell and Hamilton. Another researcher who mentioned the han was Riefstahl. and Ismail Hakkı was the first to describe the structure and its inscription.

DATE

It was finished in the month of Ramadan 637 H (1230 AD) (dated by

inscription).

REIGN

OF

Alaeddin Keykubad I (1220-37)

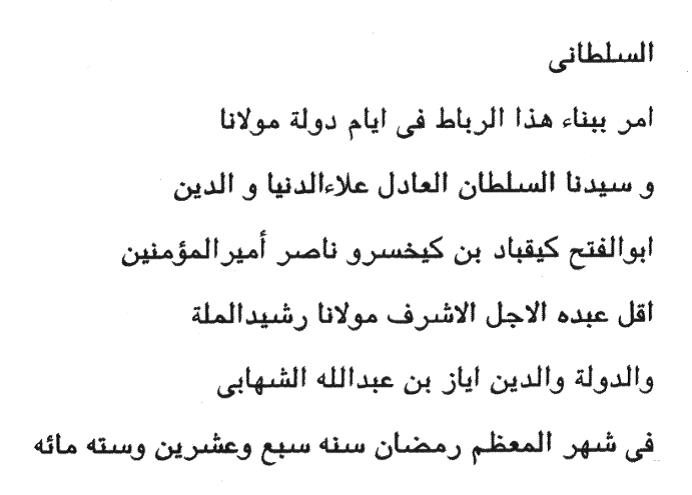

INSCRIPTION

The inscription block above the entrance door of the covered section is written in Seljuk naskhi style calligraphy and consists of seven lines in Arabic. The block measures measures 1.46 x 0.90 cm. It is interesting to note that the inscription describes it as a ribat. The inscription provides rich information: the date (month of Ramadan 627 (July-August 1230), the reigning sultan (Alaeddin Keykubad I) and the patron (Esedüddin Ayaz bin Abdullah eş-Şihabi). It also describes the han as a "ribat". It reads as follows:

The inscription above the entrance door of the covered section in written in Seljuk naskhi style calligraphy and consists of seven lines in Arabic. It reads as follows:

1) It belongs to the Sultan

2) This ribat was ordered to be built during the reign of our master (mawlana)

3) And our lord (sayyidna), the just sultan 'Ala al-Dunyawa al-Din Abu al-Fath

4) Kayqubad b. Kayhusraw, the victor [for] the Commander of the Faithful, by

5) the humble servant of our most exalted and noble master (mawlana), the

6) rightly guided [one] of the nation, the state and the faith, Ayaz b. 'Abdullah

7) al-Shihabi in the great month of Ramadan of the year 627.

PATRON

The patron of this han is a member of the powerful Byzantine-Seljuk

Mavrozomes family which dominated this historically-active region for the early

years of the Seljuk Empire.

According to the inscription of seven lines above the covered section portal, this han was built in the reign of Alaeddin Keykubad by his freedman and emir Esedüddin (or Izzeddin) Ayaz bin Abdullah eş-Şihabi.

A little background information is needed to understand this rich region and the role of this patron. In 1197, Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev I lost the throne to his brother, Rükneddin II Suleyman Shah (r. 1196-1204) based in Tokat. While in exile in Byzantine lands, Rükneddin died and Giyaseddin appealed to the Byzantines, and in particular, to his father-in-law, Manuel Maurozomes, to retake the throne. Manuel Maurozomes was a member of the family of Comnenus. Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev captured Byzantine Laodicea and gave its control to his father-in-law. This region became a buffer state between the Seljuks and the Byzantines, and then was totally annexed by the Seljuks in 1206. After the Seljuk conquest, Byzantine Laodicea became Seljuk Ladik (modern day Denizli), the provincial capital of the Seljuk west. Seljuk institutions were built in the region, such as the Ulu Camii of Denizli and the caravanserais of Çardak (1230), Haci Eyuplu (1235) and Akhan (1253). This was an active trading area and a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural region: Greeks, Turks, Crusaders, Arabs, Jews, Saracens, Venetians, Georgians, Pechenegs, Mongols, Slavs, Kipchaqs, and Armenians all lived and traded here.

The patron of the Çardak Han, Esedüddin Ayaz bin Abdullah eş-Şihabi, was a mirahur (keeper of the Sultans horses) of Alaeddin Keykubad and a Seljuk viceroy (Sahib). He was originally from Syria, and was known as Atabek Ayaz. Arab historians, such as Ibn al-Athir and Abu al-Fida, relate that he first served the Artukid Sultan, becoming an influential bureaucrat and even marrying one of the sisters of the sultan. When the sultan died in 1200, he became the Artukid sultan for a short period, but was dethroned. Knowing that his life was in danger, he accepted the invitation from the Seljuk Sultan Rükneddin II Suleyman Shah to come to Konya to serve the Seljuks. He had been invited in order to supervise important building projects, which he had already done for the Artukids. He served under Izzeddin Keykavus I and was at his side when he captured the Black Sea port of Sinop in 1214. He worked on the repairs of the fortress of Sinop in 1215 and those of the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya (1219). He is listed on the inscriptions of this important mosque as the mütevelli (supervisor). It is known that he employed architects and workmen from Syria on this project, and he may have done the same for the Çardak Han. He later supervised the construction of the walls of Konya, and, as a result, one of the gates at the southeast of the city was called the Ayaz Kapi (Door of Ayaz). From 1226-28, he supervised the repairs and renovations of the walls of Antalya, with his name appearing once again on the inscriptions. He worked in the royal palace as the last emir of Alaeddin Keykubad. It is believed that he died in 1231, and thus, this han may have been his last project.

BUILDING TYPE

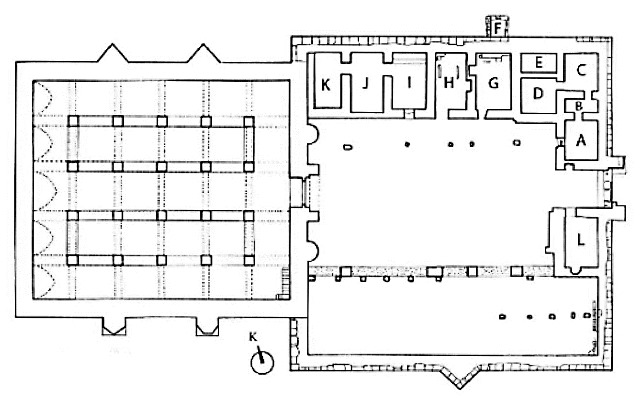

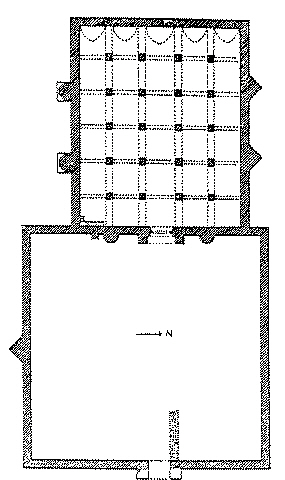

Covered section with an open courtyard (COC)

Covered section smaller than courtyard

5 parallel naves of equal width running perpendicular to the rear wall

6 lines of support cross vaults parallel to the rear wall

DESCRIPTION

The Çardak Han

han comprises the typical Seljuk plan of a covered section for lodging and an

open courtyard with service facilities located in front of it. The covered

section is located to the west of the courtyard and is smaller than the

courtyard. The han is built on a gently sloped terrain and is oriented

east-west.

This han is significant as it is the first known example of several unusual architectural features and building techniques:

1) The Çardak Han is the oldest example of a covered section with 5 parallel naves instead of the habitual three.

2) The width and height of the central nave is distinctive, as is the ladder that ascends from the covered section to the roof.

3) The use of differently-shaped support towers on the exterior walls of the covered section

4) The set of stairs up to the roof, a feature that is seen as well in the Kuruçeşme Han

5) Lack of slit windows in the covered section

Courtyard:

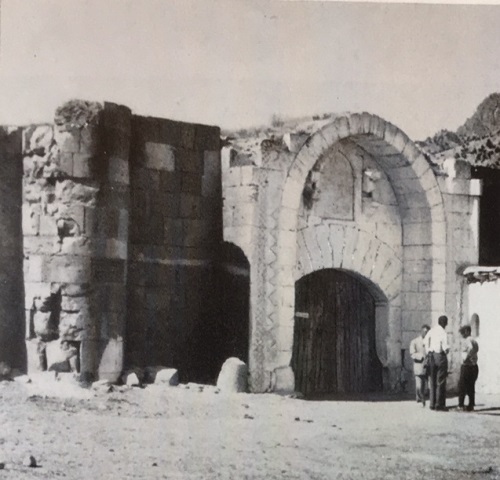

Unfortunately, the main courtyard portal of the han has been destroyed. The courtyard, which was buried until 2006, was uncovered during the excavations made by the Denizli Museum Directorate. It is believed that the courtyard was built soon after the covered section was completed.

Entry to the courtyard is from the east. The courtyard is not on the main axis of the covered section, but is shifted slightly south. An iwan is located immediately after the crown gate. Rooms for attendants are to the north of this iwan and other rooms are to the south of it.

The spaces on the northern section of the courtyard served a variety of service functions:

Bath: A bath, comprised of a suite of five rooms covered with barrel vaults, is located in the northern section of the courtyard. Terracotta water pipes and a water reservoir were discovered outside the wall and indicate that a bath was provided directly to the right of the portal, which is the standard plan for Seljuk hans. The excavations have revealed the locations of the caldarium (hot) and the two tepedarium (warm) rooms, the furnace room and the water tank. The upper section of the bath is covered with bricks.

Service rooms: The functions of the remaining 5 rooms on the north side of the courtyard have not yet been determined, but many pottery fragments and ash found the rooms which may indicate that they were used as a kitchen or bakery. Three of the rooms are internally interconnected with only one entry onto the courtyard. The covering material and construction techniques of these rooms have not yet been determined. One of the rooms could have been a bakery, as suggested by the burned wood pieces and ashes found during the excavations.

Arcade: The southern side of the courtyard is comprised of an arcade, indicated by the pier bases found at the foundation level. The south courtyard wall is built with gray limestone blocks and has a triangular buttress of the exterior. The northern wall was built of poor-quality stone and only the foundation level remains.

Mosque: The rectangular room to the left (south) of the entrance iwan served as the mosque, a configuration similar to what is seen in the Altinapa, Kizilören and Kuruçeşme Hans. It is oriented north-south and is entered directly from the courtyard via a door. The mihrab niche is located in the southern wall. Traces found during excavations indicate that the building was covered with a pointed vault running in the north-south direction.

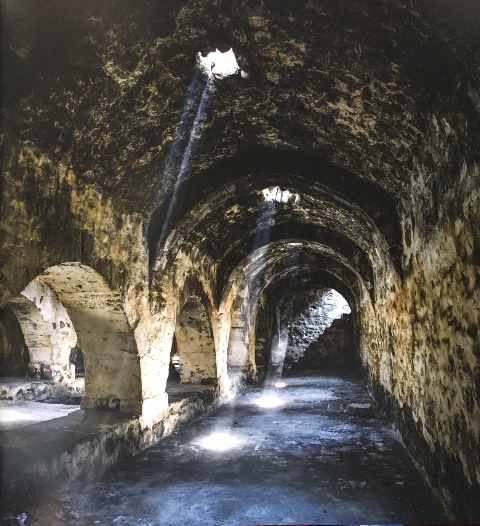

Covered section:

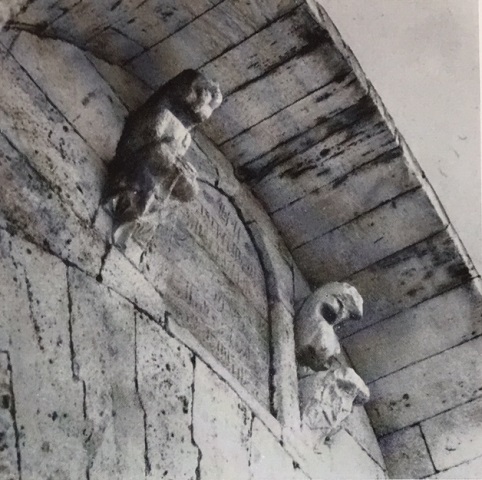

The portal of the covered section is on the same axis as the portal to the courtyard. Its upper parts have collapsed. It has geometric decorative elements and two lion consoles with muqarnas elements flanking the inscription (see below).

The covered section is smaller than the courtyard. The covered section comprises five naves. The middle nave is wider and higher than the side naves (4.40m vs. 3.40m). The naves consist of four support walls connected to each other under pointed belt courses, supported by five piers each. 5 naves created by four rows of five piers. The naves are covered with two-pointed barrel vaults running east to west. These 20 square piers, all built in the same scale and form, join the wall masonry on the side of the middle nave and are surmounted by triangular imposts, some of which have beveled corners. One of these imposts is decorated with two symmetrical fish figures and another with a bull head figure.

There are no slit windows in the walls of the covered section, which is an unusual feature. The only source of lighting comes from the 19 square skylight openings in the roof of the vaults. The Çardak han is similar to the Sari, Elikesik, Işakli, and Evdir Hans in that it does not contain slit windows in the covered section.

There are raised loading platforms on both sides of the middle nave. These loading platforms are located between the piers, and are originally believed to have been 0.70m high. The walls of the platforms are solid and were covered with concrete after the backfill material was removed.

A set of stairs in the south-east corner leads from the interior of the building to the roof.

The exterior side walls are reinforced by six unevenly-spaced support towers of varied shapes, two of which are cylindrical and flank the portal leading into the covered section. Cylindrical buttresses are not common in Seljuk architecture. Two are hexagonal and two are octagonal. There are three waterspouts at the upper parts of the southern and northern walls.

Construction techniques: The analysis of the technical features of the walls indicates that the covered section was built first. The walls of the covered section are not bonded to the walls of the courtyard section. The walls of the service facilities are technically simpler. The construction material is not the same throughout the building: well-cut yellow stone on the eastern and southern walls (those visible from the road) and low-quality porous limestone on the northern and western sides. The covered section is built of better quality stone blocks than the courtyard walls which were made of pitch-faced stone. As is generally the case, larger stone blocks were used in the lower courses of the walls. The walls of the covered section were built with greater attention, and the walls of the covered section are thicker than those of the courtyard.

EXTERIOR

The exterior walls of the covered section are reinforced by 4 differently-shaped support towers: two triangular on the north side and two rounded ones on the south. There is also a triangular tower on the south side of the courtyard. The triangular support towers on the north side of the covered section are similar to those seen at the Alara, Ertokuş, Sari and Şarapsa Hans. The Ezine Pazar Han is another example displaying pointed triangular towers on one side and differently shaped towers on the other sides. The domed roofs and squinches of the bath facilities are built of brick.

BUILDING MATERIALS

Byzantine reuse spolia stones, including carved stone pipes, probably taken from the nearby Charax Castle, have been used in the walls. It is estimated that 25% of the stone blocks used in this han are spolia blocks.

Many mason marks can be seen on the stones of the building.

DECORATION

Two full relief sculptures of lions are the stars of this han. Indeed, the most significant elements are two carved stone lions on either side of the inscription plaque above the portal of the covered section. The lions, sitting on their haunches with their backs to the wall and face forward. The lion on the left is in better condition than the other. They project 0.36m and face frontally. They stand on two consoles with muqarnas decoration. Highly-expressive, their mouths are agape and their tongues are visible. They have round cheeks and almond eyes, but the heads are not depicted in detail. Lions are a frequently-seen decorative element in Seljuk art, and fine examples can be seen in other hans, notably in the Ak, Alara, Çardak, Cay, Incir, Kesikköprü Hans. Although the lion figure is popular in Seljuk art, here it comes with a tongue-in-cheek element: the name of the patron, Esedüddin (Asad al-Din) means Lion (Defender) of the Faith. These two figures are examples of the apogee of Seljuk decorative arts.

Other decorative elements include fretwork and braids on the covered section door, and rosettes and rows of chevrons on the sides of the entry door. The borders on each side of the portal, and include octagonal, triangular and knot-like elements.

Additional interesting figural representation can be seen on the capitals of the piers in the central nave of the covered section. These include a bulls head figure with pointed horns and flaring nostrils. Another sculpture includes two symmetrically placed fish on the capital of the third pier. The heads of the fish point upwards, and have three, pointed fins on their backs. A third decorative sculpture, a human (or animal) head is located on the capital of the fourth pier. It is highly stylized, with large ears. These figures are believed to be cosmological symbols. It is interesting to note that such an important amount of figural decoration is found in the covered section, on the capitals of the piers, with a limited amount of floral and geometric ornamentation on the portal, which is the opposite of the general Seljuk pattern of placing all the decoration on the portal. Yet those two roaring lions are all that is needed to make a statement about this importance of this han.

DIMENSIONS

Total external area: 1850 m2

(22.50

x 27 m)

Area of covered section: 610m2 25 x 29.5m)

Area of courtyard: 1020m2 (34 x 32m)

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

After the Seljuk period, the han continued to serve during the Beylik and Ottoman periods, when a derbent (military station) was set up for the security of the pass. It was used for grain storage during World War I and the Turkish War of Independence (1920-1922). Later it was used as a sheepfold. It was repaired in the 1920s and again used for grain storage and animal pens up until the 1950s.

A program of cleaning and excavation was carried out by the Denizli Museum in the summers of 2006-2008. This excavation exposed the layout of the courtyard and revealed that the han had a mosque and a bath located next to the entrance of the courtyard on the southern and northern sides. The han is not in use today.

The han is in good shape and is quite beautiful. It stands empty and can be visited. There are apparently plans to convert it into a tourism business. Visitors can reach the village by taking a minibus from the Denizli bus station.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Arundell, F. V. J. A Visit to the Seven Churches of Asia, with an Excursion into Psidia: Containing Remarks on the Geography and Antiquities of those Countries, a Map of the Authors Routes and Numerous Inscriptions. London: 1828, p. 103.

Aslanapa, Oktay, Anadolu'da İlk Türk Mimarisi, Başlangıcı ve Gelişmesi. Ankara: Atatürk Kültür Merkezi Yayını, 1991.

Bakırer, Ö. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Yapi Kitabeleri. V Milli Selçuklu ve Kültür Medeniyeti Semineri Bildirileri. Konya : 1996, p. 37-51.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 1, pp. 354-358.

Demir, Ataman."Anadolu Selçuklu Hanları. Çardak Han" İlgi, 58 (1989), pp. 20-23

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 281-287.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961, pp. 59-61, no. 15; vol. 3, p. 130.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, pp. 485.

Hamilton, W. Researches in Asia Minor, 1842, pl. I, p. 505.

Hillenbrand, R. Islamic Architecture: Form, function and meaning, 1994, fig. 6.50, p. 552.

Karpuz, Haşim. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, vol. 1, p. 244.

Kutlu, Mehmet. Seljuk Caravanserais in the Vicinity of Denizli: Han-Abad (Çardak Han) and Akhan [masters thesis]. Ankara: Bilkent University, 2009.

Özergin, M. Kemal. "Anadolu'da Selcuklu Kervansaraylari", Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 146, n. 18.

Peacock, A. C. S. (2014). The Seljuk Sultanate of Rūm and the Turkmen of the Byzantine frontier, 12061279, Al-Masaq: Journal of the Medieval Mediterranean, 26:3, 267-287, DOI: 10.1080/09503110.2014.956476.

Pektaş, Kadir. "Çardak Han" in Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı, 2007, pp. 160-173 (includes bibliography), p. 455, 485.

Pektaş, Kadir. Çardak ve Çevresindeki Türk Devri Eserleri Üzerine Bir Araştirma. Ululararasi Sosya Araştirmalar Dergisi, 6 (25), 2013.

Parla, C & Altınsapan, E. Atabek Ayaz ve Figürlü Benzemeleriyle Denizli Çardak Han. Ataturk Kültür Merkezi Erdem Dergisi (51), 2008, pp. 195-215.

Rice, Tamara Talbot. The Seljuks in Asia Minor, 1961, p. 206.

Riefstahl, R. Meyer. Turkish Architecture in southwestern Anatolia, 1931, p. 25.

Speros Vryonis, J. The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamization from the Eleventh through the Fifteenth Century. Berkeley, 1971.

Tavernari, Cinzia. Stones for Travellers: Notes on the Masonry of Seljuk Road Caravanserais. In Blessing, Patricia and Rachel Gosgarian, eds. Architecture and Landscape in Medieval Anatolia, 1100-1500. Edinburgh, 2017, pp. 73-78, pl. 6, fig. 3.4.

Uzunçarsili, I. H. Afyon Karahisar, Sandikli, Bolvadin, Çay, Işakli, Manisa, Birgi, Muğla, Milas, Peçin, Denizli, Isparta, Atabey ve Eğirdir Kitabeler ve Sahip, Saruhan, Aydin, Menteşe, Inanç, Hamit Oğullari Hakkinda Malumat. Istanbul, 1929, p. 210-12, pl. 58-60.

Whittow, M. Survey of Medieval Castles of Anatolia: Çardak Kalesi. Anatolian Archaeology (1), 1996, p. 355- 358.

|

inscription plaque |

Photo by Erdmann (#74) |

Photo by Erdmann (#76) |

Photo by Erdmann (#75) |

|