The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

CINCINLI HAN

A massive han, now in ruins, had two inscriptions which have now been lost. It is believed to have been one of the seven hans built by Mahperi Hatun in the Tokat region.

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.2, p. 481.

|

|

Bilici, vol. 3, p. 491. |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 470; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 475; photo I. Dıvarcı |

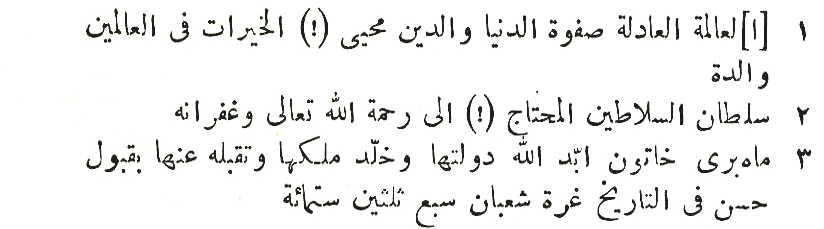

inscription in the Karamağara mosque |

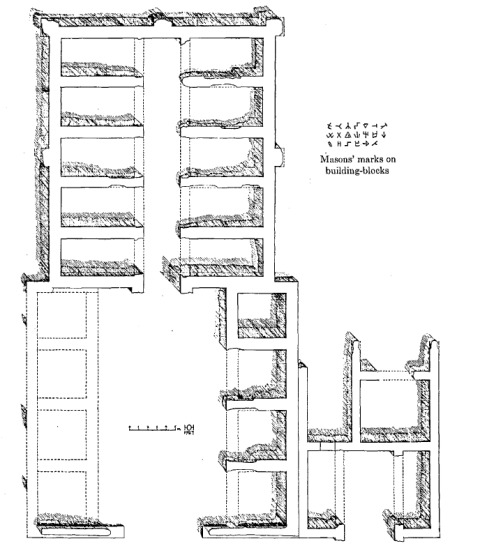

plan drawn by von der Osten, 1927 |

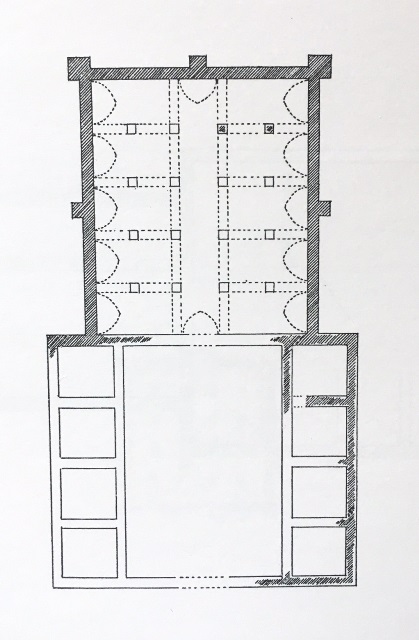

plan drawn by Erdmann |

|

DISTRICT

66 YOZGAT

LOCATION

39.774279, 35.542938

The Çınçınlı Han is located on the remote Yozgat-Akdağmedeni Road (E88), 16 km north of Saraykent, formerly known as Karamağara, in the Saraysu Valley. This caravan road led north from Kayseri, and the han is located between Kayseri and Zile. The Akdağmadeni-Yozgat highway passes to the south of the han. The village of Ilica, with its historical thermal baths, is located near the han.

The han is located on an alternative route that connected Amasya-Samsun and Tokat without stopping at Sivas. The next stopover station in the direction of Zile is the Çekereksu Han, also considered to have been built by Mahperi Hatun. A dam has been built in this region, whose waters most certainly covered over the traces of other hans along this route.

There are thermal baths to the right of the han with numerous spolia stones, which most certainly indicate that it was originally the site of a Byzantine-era thermal spa.

NAMES

It is also known as the Saraykent-Çincinli (or Çimcimli) Sultan Han, Sarayköyü Han, Sarayözü Han.

When H.H. von der Osten carried out his field research in 1933, he called the han the Cimcimli Sultan Han. It is not clear when it became converted to Çınçınlı or Çinçinli. Cimcimli recalls the Turkish word of cimcime, which denotes a petite and lively woman. It also recalls the word çimmek, which means bathing or swimming. As the historic baths do exist not far from the han, the word 'cimcimli' could very well have been derived from the verb çimmek (to bathe).

Other researchers have called it the the Sarayköy Han after the settlement and the river passing in front of it, and the Saraygözü Han.

DATE

It has been traditionally dated by the now-lost inscription which was located on the minaret of the Karamağara (Saraykent) mosque, which stated that the han was built in 1238

by Mahperi Hatun.

According to the two inscriptions belonging to the han, it was completed in Hijri 637/1239 A.D. The builder is Mahperi Hunat Hatun. There is a difference of approximately five to six months in the inscription dates. This situation is also noted in the inscriptions of the Pazar Hatun Han, and is related to the different construction dates of the two sections of the hans, which correspond to the different completion dates of the two sections. Considering these inscriptions, it can be said that the covered section was completed in the month of Safer of Hijri 637 (November, 1239) and the construction of the courtyard began immediately following this date. The courtyard was finished in the month of Şaban month of Hijri 637 (February, 1240).

REIGN OF

Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev

INSCRIPTION

H. H. von der Osten conducted field research along the route where the han is situated and stated that the road continued through Kesikköprü. He explored the han and mapped its plan. Osten stated in 1927 that there was an inscription belonging to the han, located in a mosque in the village of Karamağara, and claimed that this inscription had been read by Wittek. However, the location of this inscription is unknown today.

Two different inscriptions concerning this han have been discussed in the past and read; however, both are lost today. The first inscription was read by Wittek in 1929. Wittek viewed the inscription in the Karamağara mosque and said that the upper part of the inscription was lost and that its missing parts could probably be found in the han. However, they have never been located. Wittek took a casting of this inscription and published the three lines written in Seljuk-style naksh calligraphy as follows:

Wise, sincere of the world and religion, the charitable builder of two worlds and the mother, the sultan of the sultans, aid in the help of the compassionate, merciful Allah, Mahperi Hatun May Allah forgive her and bless her power and rule and may He destine us to meet her in a good way built in the month of Şaban in the year of 637.

The other inscription was seen and published by Bittel following his research in the region at the beginning of the 1940s. It is practically identical to the Karamağara inscription and was found in the village of Cotelli, now known as Gülşehri. The calligraphy style and the wording are similar, but the month is not Şaban in this inscription, but rather Safer.

PATRON

It is generally attributed to Mahperi Hatun. According to the two

inscriptions belonging to the han, it was completed in Hijri 637/1239 A.D. The

builder is Mahperi Hunat Hatun.

BUILDING TYPE

Covered section with an open courtyard (COC)

Covered section is smaller than the courtyard

Covered section with 3 naves (a middle nave and 2 lateral aisles) perpendicular

to the rear wall

5 lines of support vaults parallel to the rear wall

DESCRIPTION

The han is oriented northeast. It consists of a covered section used for lodging with an open courtyard in front of it which included service areas. The crown door of the covered section is on axis with the door of the courtyard. The covered section is smaller than the courtyard section. This han displays the same features as other Sultan hans built in 13th century. The entrance of the han faces west.

Courtyard: The courtyard is situated to the west of the covered section and is wider than it. It has an almost square plan. Considering the plan prepared by Osten and the current ruins, there were open and covered cells sections heading towards the courtyard on the north and south. The entrance of the courtyard is not on axis with the crown door of the covered section.

A unit with four elements side by side leaning against the wall to the rear of the south wing of the courtyard can be seen in the plan of Osten; however, only two are visible today. There are no support towers along the walls of the service areas of the courtyard.

There is a bath along the western wall of the courtyard, but the walls of the han and the bath are not connected to each other. It is in ruins today. Osten states that he had heard from the locals that the bath was actually a hot spring. This spring has now dried up, but it was the source of the hot water for the bath at that time. However, the presence of verdant vegetation in the region indicates that the water supply has not completely disappeared. The bath has a rectangular plan. There is a dressing room with two support lines at the entrance in the east-west direction. Entry to the caldarium is through this room. The water tank is located on the western side of the bath. The differences in the construction materials and techniques in this bath and the han indicate that the bath was built after the construction of the han.

Covered section:

The crown door of the covered section is now completely in ruins. It projected from the main wall in the direction of the courtyard, but its other architectural features cannot be determined.

Recent field research conducted by Dr. Osman Eravşar confirms that the covered section consisted of three naves in the north-south direction perpendicular to the rear wall, with side sections parallel to the rear wall. These naves were covered with pointed vaults at a lower level. On each of the naves heading in the north-south direction, there were four support lines with four square piers each. The support lines in the north-south direction were connected to each other by pointed arches in the same direction. The central nave heading towards the east-west direction was covered with a vault at a higher level compared to the other naves.

There is no evidence indicating the presence of loading platforms in the covered section. The east wall, which is solid, does not have any openings for lighting. However, there are slit window openings in the middle of the second and fourth naves.

EXTERIOR

The eastern wall of the covered section was reinforced by square support towers placed in the corners and at mid-section. The plan drawn by Osten shows a support tower in the middle of the north and south walls. Traces of the south tower have remained, but the northern one has completely disappeared. It is not possible to determine the original roof system of the covered section. The rooms of the north wing are completely below ground level today.

BUILDING MATERIALS

Smooth-cut stones were generally used for the construction of the han. The outer surfaces of the walls were lined of smooth-cut stones. A mixture of broken stones and mortar was used as infill. Most of the original stones have been removed today. The solid east side wall contains larger blocks in the lower level. Mason marks are visible on many of the smooth-cut stones. No reuse spolia material was used in the han. However, Osten had published a picture of a funerary stele found in Karamağara and wrote that it was brought here from the Cimcimli Sultan Han.

DECORATION

There are no decorative elements noted in the han.

DIMENSIONS

covered section: 23 x 26.7 m

courtyard: 31 x 26m

Total area: 1500m2

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

Both sections of the han are in ruins. In the photographs taken by Osten in

1927, the building was in much better condition and much of the original

material was visible on the walls. Today, some parts of the north and south

walls of the covered section are relatively solid up to the level of the vault

keystones. The east wall of the covered section is the most stable of the walls.

The solid walls and other cladding stones have been taken away for other

purposes over the years. The collapse of the courtyard is more severe than that

of the covered section. Villagers have indicated that the front areas of the

bath and courtyard were destroyed by earth-moving equipment during the work

carried out to widen the road.

At the present time, the han is filled with construction waste which has been dumped inside of it. This monumental han and the historic area around it have been abandoned and will surely disintegrate and totally collapse. The legend of Mahperi Hatun deserves better recognition.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı : Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 3, p. 491.

Bittel, K. Kleinasiatische Studien. Istanbul, 1942, p. 45 n. 32.

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 470-475.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961, pp. 40-42, no. 37.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 488.

Karpuz, Haşim. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, v. 2, p. 481.

Osten, Hans Henning von der. Oriental Institute Communications Explorations in Hittite Asia Minor, no. 6. Chicago, 1933, pp. 26-29.

Osten, Hans Henning von der. Discoveries in Anatolia, 1930-31. Oriental Institute Communications Explorations in Hittite Asia Minor, no. 14. Chicago, 1933, pp. 100-106.

Özergin, M. Kemal. "Anadolu'da Selcuklu Kervansaraylari", Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 147, n. 21.

Wittek, P. Von der Byzantinischen zur Turkischen Toponomie. Byzantion 10, 1935, pp. 11-64.

©2001-2025, Katharine Branning; All Rights Reserved.