The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

ESHAB-I KEHF HAN

Built to welcome visitors coming to an ancient interfaith pilgrimage site, the Eshab-I Keyf Han displays an interesting layout with a separate stable section. The han was designed as part of the Eshab-i Kehf Complex, which includes a fort (ribat), later used as a dervish lodge, and a mosque.

|

|

|

view from rear of han onto the ribat |

|

|

|

|

|

|

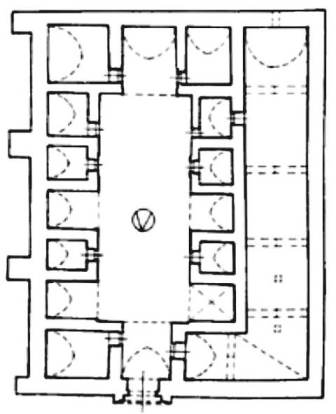

plan drawn by Özkarci Eravşar, 2017. p. 520 |

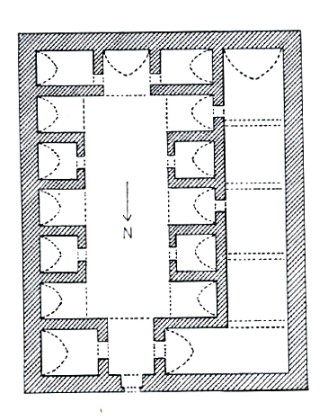

plan drawn by Erdmann |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 519; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 522; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

stable section |

|

commemorative stamp, 2001 issue |

|

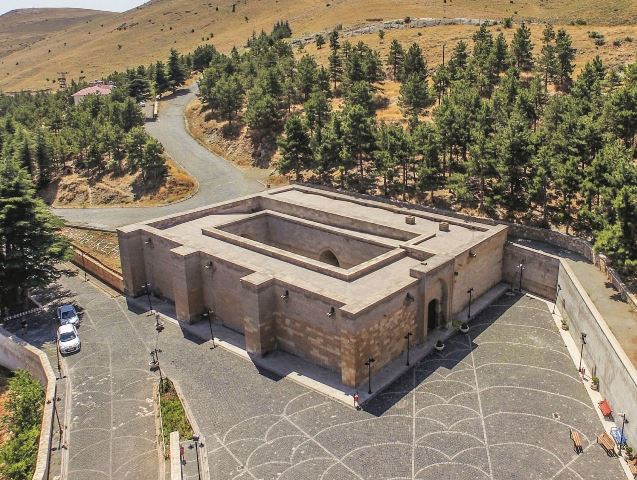

photograph by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

DISTRICT

46 KAHRAMANMARAŞ

LOCATION

38.248619, 36.855041

The Esab-i Kehf Han is located 7 km north of the city of Afşin, 16 km past Elbistan on the Göksun road. It is situated directly in front of the Eshab-i Kehf cave. The water flowing from the spring in this cave is considered holy, much like the ZamZam water of Mecca. There is no caravan road passing in front of the han, so it is believed that it was built for the pilgrims coming to the cave, rather than for commercial purposes. The han is a part of a complex which includes a fort (ribat) and a mosque. These structures have been modified over the years, but the han has retained its original plan. The han was not built specifically on a trade route, but is linked to the Aleppo-Elbistan-Kayseri trade route.

Kahramanmaraş was an important town of the Anatolian Seljuks, due to its geographical position and location at a very strategic point of Anatolia. Researchers believe that there were many architectural works built by the Seljuks here, but all have been destroyed. However, there are several hans which remain, including this one. This han was built not only for commerce, but to house the "Friends of the Cave" who came to visit the holy site.

NAMES

There is no inscription plaque furnishing the name of the han, so it

is generally known as the Esab-i Keyf Han after the site. It is referred to in

Ottoman period sources as the Afşin Han.

DATE

First quarter of the

13th century

REIGN OF

Alaeddin Keykubad I

INSCRIPTION

The han has been restore various times since 1960 and its inscription was tranferred to the portal of the neighboring Eshab-i Keyf mosque, originally belonging to the ribat, which includes three lines of Seljuk naskh calligraphy. It reads as follows:

"This ribat was built in the time of the glorious sultan, exalter of the world and the Faith, the great conqueror, the helper of the commander of the believers, the son of Keyhusrev, Sultan Keykubad, by Emir Nusretuddin Hasan, son of Ibrahim - May Allah bless him and have mercy upon him - in the year 630."

It is believed that the han was built at approximately the same time.

PATRON

It can be seen from the mosque door inscription that the patron was Emir Nasr

ad-Din Hasan ibn Ibrahim.It is believed that this same Emir was also the patron

of the Eshab-i Kehf han. A former slave, he became governor of Maraş under Alaeddin Keykubad

from 1211 until at least 1232. Ibnul Adim, who visited the area in 1230, speaks

of an imaret (soup kitchen) for visitors, which corresponds to the dates of the

appointment of Emir Nusretüddin Hasan.

BUILDING TYPE

Concentric

DESCRIPTION

The setting:

This han is located in a highly scenic and remote area, atop a small mountain, offering a majestic view of the countryside below, ringed on four sides by mountains. The site of Eshab-i Kehf cave is associated with the Christian story of the Seven Sleepers of the Cave which also appears in the Qur'an, Sura 18, The Cave Sura (al-Kahf) as the Companions of the Cave". In Christian and Islamic tradition, the Seven Sleepers is the story of a group of youths who hid inside a cave to escape religious persecution and emerged 300 years later. The Sleepers are the subject of a famous poem by Goethe. The cave has been a sacred pilgrimage site since ancient times, calling those who visit it as the "Friends of the Cave." It was designated as a holy place by Christians, who built additional religious structures around the cave. It is believed that the original complex, including a structure known as "the Jesus Masjid", was built in 446.

The complex:

This han is part of a complex: in addition to the han, there is a mosque (once a Byzantine church) and a ribat (fort). All form a building complex called the Eshab'ül Kehf Külliyesi. The church was a pilgrimage site in Christian times, and the whole complex has continued as such in Islamic times.

The ribat:

The Esab-i Kehf ribat, with its finely-decorated portal, is the highlight of this complex. Sitting high on the hill, the ribat dominates the entire complex. It is one of the most outstanding examples of Seljuk military architecture. Ribats were used for defense purposes, military garrisons and as dervish lodges by various Sufi religious orders. The han is situated below it, and is a more modestly-decorated structure. The facades of the two structures face each other. The ribat served first as a soup kitchen (imaret) and later as a dervish lodge. The ribat was commissioned by Maraş Emir Nusretüddin Hasan Bey, during the reigns of Izzeddin Keykavus I and Alaeddin Keykubad, between 1215 and 1234.

A large tandir (underground pit oven generally used for baking flatbread) is located above the ribat, on a high hill. This oven is located next to a large flat rock used for rolling the bread dough. Similar tandirs have have been discovered in other hans.

The mosque:

Next to the ribat is the mosque, built on the site of the former pilgrimage church named the John Manuk Church. This church was mentioned by Erdmann, referring to Babinger. Kiepert also marked the church on his map. You definitely feel that you are in a Christian church when you are in this mosque. Extensive reuse spolia material and marble column capitals from the former church remain inside the mosque. Many of these are notable examples of marble stonecutting. The facade, doorway, mihrab and piers were built of finely-dressed stones. The arches and roof are made from brick, and the columns and their capitals are of marble. The mihrab is framed at the top by a lintel of spolia. The mihrab is topped by a round arch with an oyster shell hood framed by acanthus leaves. To the west of the prayer hall is an aisle known as the "Isa (Jesus) Masjid" separated by two massive piers; it is thought to belong to a church commissioned by Emperor Theodosius II in the first half of the fifth century. This aisle is raised from the other two aisles in the east and has a small marble mihrab comprised of spolia stones from the old church.

The original construction date of the mosque is not certain. Ibnul Adim, the Arab bibliographer and historian from Aleppo, came to the site in 1230 and affirms that there was an imaret and a large stone tomb built in front of the cave, which was converted into a mosque at a later date. Some researchers believe that the mosque was built in 1215-34 by Nusr al-Din Hasan, son of Ibrahim, the Emir of Marash, during the reign of Alaeddin Keykubad. Others believe that the mosque was built much later during the time of the Dulkadiroğullari Beylik (14th century) or even during the Ottoman period.

The han:

The han is oriented north-south and the entrance faces south. The han has a rectangular plan, and comprises a long courtyard surrounded by rooms of different sizes.

The plan of the Eshab-i Kehf Han differs in certain features from the traditional Seljuk Han plan. It consists of open and closed rooms arranged around a long, narrow courtyard. Directly opposite the entrance is a large iwan with vaulted rooms on each side. The stable section to the west is also unusual. This concentric plan is similar to the plans of the Alara and Tercan hans. This han plan is more similar to the plan of a medrese than a han with the traditional covered section and open courtyard plan.

Courtyard:

The portal protrudes from and is taller than the entrance wall. The damaged crown door leading into the courtyard was restored during the repairs made to the han. The pointed arch of the crown door projects slightly from the façade and is surrounded by a border decorated at the lower level with half-stars. This is the only decoration in the han.

The courtyard contains open and closed rooms on three sides (8m wide and 21 m deep). There are two open iwans on both the east and west sides, with closed rooms between them. The south (entry) side has a larger iwan flanked by two closed rooms. The room located to the left of the entrance is wider than the other rooms and probably served as the quarters of the innkeeper. The room to the west of the entry leads to the long covered hall on the west of the structure. There is a series of series of three rectangular rooms opposite the entrance. All are designed as iwans. The southwestern iwan is covered with a cross vault while the others are covered by pointed barrel vaults.

The most interesting element of the plan is the stables section, which connects to the courtyard entrance iwan. This han shows an advanced plan with the stables isolated from the other sections to ensure greater comfort for the travelers. The concentric plan comprises a large, L-shaped covered area that runs along the entire western side of the courtyard. This area was used as the stables. This long hall on the western side was covered with a pointed barrel vault. There are no window slits in the walls. Access to the stables is just inside the entrance to the han, to the right. These stables are isolated from the other sections of the courtyard, which are thus isolated from the noise and smells of animals. A window in the last small room on the west side of the courtyard gives a view onto the stable area for supervising the animals.

As there is no caravan road passing in front of the han, it is believed that the han was built for the pilgrims coming to the cave, rather than for commercial purposes.

No bath has been noted. The water source was from the spring located below the ribat. Inside of the ribat there is an underground spring which links to the Esab-i Kehf underground springs and caves, 3 miles to the west.

BUILDING MATERIALS

The walls of the han were built with smooth-face stone, although old photographs reveal that pitch-faced stone was used for the outer walls and smooth-faced on the interior sides, piers and surfaces. Drainage pipes were placed on the east walls.

EXTERIOR

The outer walls of the east side were reinforced by four square support towers. It was not necessary to add support towers to the west wall, as it was built flush to the mountainside.

DECORATION

The only decoration in the han appears on the borders of the crown door. The arch of the portal door of the ribat is filled with a highly-decorated program of muqarnas (stalactites) and rosettes. The portal of the han is simple, and the inscription plaque has been lost.

DIMENSIONS

850m2 (external area)

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

The han was fully operational until the year 1910, after which it went out of service and began to deteriorate. It was repaired in 1960-63. The entire complex is in excellent condition, and was completely restored in 2008. Many of the original architectural elements were lost during the repair, but the plan and construction elements have remained intact. The han may be visited (if closed, ask guardian in the house above to open). The damaged crown door was restored during repairs made to the han. In August, 2018, Fatih Mehmet Güven, the mayor of Afşin, announced that he wishes to apply for the site to be on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2019. It was already been accepted on the UNESCO tentative list of monuments on April 13, 2015.

The site is highly-frequented on Fridays for prayer and on the weekends for picnics, and the drinking water of the spring below the ribat is highly-prized. The complex, with its history, prominence of site, emotional impact, serene setting, and ecumenical spirit retains the original spiritual atmosphere of the Christian pilgrimage site. Today, visitors tie votive wish ribbons to the trees and bushes on the hill above the complex where they flutter in the wind as they have for centuries you, too, should do the same to honor this site of interfaith peace.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Altun, Ara. An Outline of Turkish Architecture in the Middle Ages, 1990, p. 199.

Aslanapa, Oktay. "Anadolu'da Ilk Türk Mimarisi." Ankara: Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu, 1991, p. 118.

Bektaş, Cengiz. Selçuklu kervansarayları, korunmaları ve kullanılmaları uzerine bir öneri = A proposal regarding the Seljuk caravanserais, their protection and use, 1999, pp. 128-129.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 2, pp. 98-99.

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 519-522.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961, pp. 187-188, no. 59.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 497.

Ibn al-Adim. Bughyrat al-talab fi tarikh Halab = Everything desirable about the History of Aleppo. 11 vols, 1986-90, p. 334.

Karpuz, Haşim. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, vol. 1, pp. 398-399.

Kiepert, R. Karte von Kleinasien, in 24 Blatt bearbeitet, 1902-1916.

McClary, Richard P. Rum Seljuq Architecture 1170-1220: The Patronage of Sultans. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016, p. 67, 73.

Müderrisoğlu, Fatih. Afşin-Eshab-ı Kehf Külliyesi Hanı, Kültür ve Sanat, 3/10 (June 1991), pp. 12-15.

Özergin, M. Kemal. Anadoluda Selçuklu Kervansarayları, Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 149, n. 35.

Özgüç, T., and Akok, M., Afsin Yakinindali Eshab-I Kehf Kulliyesi, Yıllık Araştırmalar Dergisi [Annual Journal of Research] II (1957), pp. 77-91.

Özkarcı, Mehmet. Kahramanmaraşta Selçuklu Mimarisine Bakiş, Uluslararasi Selçuklu Döneminde Maraş Sempozunu, 17-19 November, 2016, pp. 14-53.

Özkarcı, Mehmet. "Esab-I Keyf Han" in Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı, 2007, pp. 436-447 (includes bibliography).

Rice Tamara Talbot. The Seljuks in Asia Minor, 1961, p. 206.

Sümer, Faruk. Eshabul Kehf (Yedi Uyurlar). Türk Dünyasi Araştirmalari Vakfi. Istanbul, 1989.

Yinanç, Refet. Eshab-ı Kehf Vakıfları, Vakıflar Dergisi, XX (1988), pp. 311-320.

|

|

|

|

|

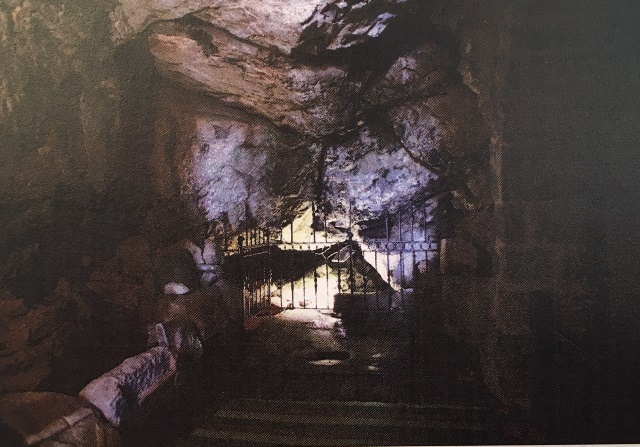

Holy Cave of the Seven Sleepers |

Holy Cave of the Seven Sleepers

|

|

view from the ribat

|

|

For further views, click on thumbnails below:

©2001-2025, Katharine Branning; All Rights Reserved.