The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

INCIR HAN

A dated and signed Sultan Han with a spectacular crown door decorated with symbols demonstrating the passion of the sultan for his wife.

Eravşar, 2017. p. 368; photo I. Dıvarcı |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 373; photo I. DıvarcI |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 371; photo I. Dıvarcı |

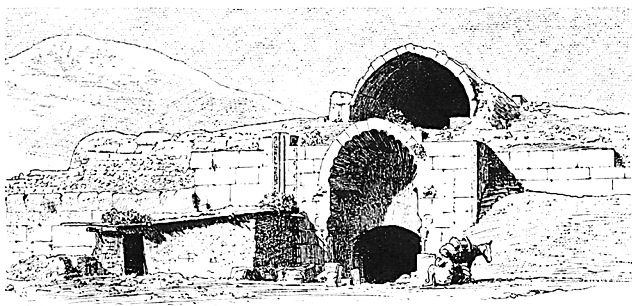

sketch of the han by Count Lanckoronski, 1890 |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

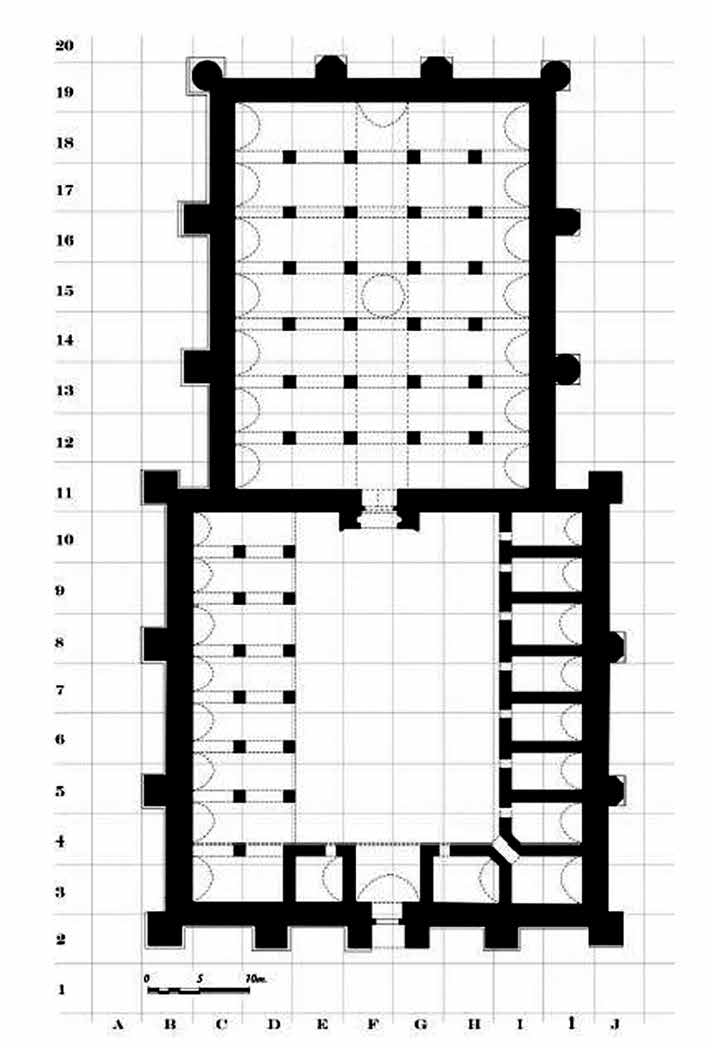

plan from Unal |

|

Lion and solar symbol on the portal Eravşar, 2017. p. 375; photo I. DıvarcI |

Coin minted by Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II in 1244, depicting the şir-i hurşid motif |

|

Star Tile found at the Kubadabad Palace. Konya, Karatay Madrasa Tile Museum, end 13th-beg. 14th c. |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 378; photo I. Dıvarcı inscription on above side niche of the entry |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

Bilici, vol. 1, p. 323 |

DISTRICT

32 ISPARTA

LOCATION

37.478583, 30.533444

This han is located on the Antalya-Isparta (Burdur) road, 88 km north

of Antalya near the town of Susuz on the Eğirdir-Antalya

caravan route. Turning left at the turnoff for Bucak, the

han will be found a short distance down the road, approximately

3 km from the village of Incirdere. The han

is located in a fertile green valley in an open area along a road loading northwest from the slope of

Mount Kocadağ. There are 4 stops along the

Antalya-Burdur Route before this han. The Incir han is preceded by

Kirkgöz, Evdir, Susuz and

the now lost Ağlasun

Hans.

The ruins of the latter have

been

recently

discovered.

The

distance between the Susuz Han and the next stop, the Ağlasun Han, is about 36

km, which could have been traveled easily in one day, as this road does not

include any natural obstacles.

The lake that originally supplied the han with water has since dried up.

OTHER NAMES

The name of this han means the "Fig Tree" han, perhaps in reference

to the numerous fig trees found in this area. This poetic name was attributed to

the han by the early

travelers who visited the region: Köhler, one of the first to mention it,

Schoenborn, Cuinet, Rott, Sarre and Riefstahl, who carried out the first

comprehensive study of the han. Count Karl Lanckoronski has left a very fine

sketch of the façade in his brilliant study on the classical Greek buildings in

southern Anatolia.

DATE

1238-39 (dated by the inscription)

This is a "Sultan Han", that is, a han commissioned directly by a Sultan.

Chronologically, it is the 5th in line of the Sultan Han group.

INSCRIPTION

The

inscription on the crown door of the covered section indicates the name of the

person who ordered the construction of the han, the Sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev

II and the date. It comprises four lines of fine

Seljuk-style naksh script.

The inscription reads as follows:

1) The construction of this blessed khan was ordered by

2) the most great sultan, the magnificent Shah of Shahs, master of the bowed heads of the people,

3) the lord of the sultans of the Arabs and non-Arabs, the sultan of the land and of the two seas, the Dhu'l Qarnayn of the Age, the second Alexander, the Crown

4) of the Seljuk family, Ghiyath al-dunya wa'l-din, father of victory, Kaykhusraw, son of Kayqubadh, son of Kaykhusraw, associate of the Commander of the Faithful, in the year 636 [1238-1239].

The main interest of this inscription lies in the unusual titles the sultan assumes in it. The titles attributed to the sultan in this inscription - "Dhu'l Quarnayn of the Age" and "the second Alexander" - are unusual. It is to be noted that Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II used rather boastful epithets in his inscriptions, even more so than his already proud father, Alaeddin Keykubad I. In this han, Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev uses titles never previously employed by any Seljuk sultan; calling himself the Second Alexander the Great, a rather pretentious boast in view of the fact that a few years later he would lose the battle that sunk the Seljuk empire. As a general rule, the inscriptions of Alaeddin Keykubad employed standard titles derived from those of the Great Seljuks, whereas his son Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev used a colorful and more boastful approach to describing himself. It is tempting to think that perhaps in order to cover up his lack of character, he launched into a self-promoting marketing campaign to promote his image, much as do many modern politicians. His novel approach to branding finds its echo in the decoration of the han, which displays his personal emblem of a sun on the back of a lion.

Another inscription can be seen on the right console door jamb of the covered section. The incomplete inscription reads as follows:

The clerk of this blessed han is...

|

|

PATRON

Gıyaseddin Keyhüsrev II.

According to the inscription, the han was completed in 636 H (1238 AD), with the covered section completed under the direction of Sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II. It is not known who the clerk mentioned in the incomplete inscription is, or what role he played.

BUILDING TYPE

Covered open courtyard (COC)

Covered section smaller than courtyard

Covered section with a central aisle and two side aisles on each side running perpendicular to the back wall

6 bays of vaults

DESCRIPTION

The

Incir Han, with its plan and elaborate program, is noteworthy as one of the last

western Anatolian hans built in the Seljuk period. The han formerly consisted of

a covered section, in front of which was an open courtyard with service areas.

Only the covered section remains today. It faces southeast.

Courtyard:

The courtyard section, now in ruins, is located to the southeast of the covered section and is slightly larger than it. Soil, carried by the flood waters descending from Mount Kocadağ to the east of the han, has completely filled the interior of the courtyard over the years. This soil has been recently removed and protective masonry has been built over the foundations following the recent archaeological excavations.

The square courtyard slopes down from the north to the south. The open courtyard is surrounded by enclosed spaces on the south and east sides and open arcades to the west. The entrance to the courtyard is in axis with the entrance of the covered section. An iwan, located immediately after the entrance, opens onto the courtyard. A second iwan, facing the courtyard, is located to the west of the entrance. The room in the west corner of the iwan was likely a latrine. The iwan was probably used as a fountain space directly serving the arcade, as is seen in the Sarı and Alara Hans.

The space to the east of the entrance iwan was believed to have been the quarters of the han manager. This room was adjacent to a corner room which opened directly onto the courtyard, as is seen in the Sari Han. The excavations in the courtyard have brought to light the foundations of rooms surrounding the courtyard on three sides. On the east side of the courtyard, the foundations of seven rooms with entrances to the west have been identified, almost all identical in size except for the one in the southeast corner. These rooms were believed to have been covered by barrel vaults in east-west direction. They opened directly onto the courtyard. The room in the east corner of the southeast side is thought to be the latrines and next to it is a fountain iwan.

The western side of the courtyard is comprised of an open arcade with seven units, each with a support wall with two arches carried on two piers. The sections are connected to each other and are covered with pointed vaults opening directly onto the courtyard. A drain channel has been found at the southern end of the west wall, which was probably used to dispose of waste water.

Covered section:

The crown door of the covered section is located in the southern façade. It projects from the main walls in the southern direction, but it has suffered too much damage to be able to determine its exact original composition. The upper part has fallen down. It is to be noted that the shape of this portal is different than the classic format seen up until now. The door lacks the traditional muqarnas hood.

The covered section, slightly smaller than the courtyard, is located to the east of the service spaces of the courtyard. It is comprised of a central nave with two naves on each side, borne by support walls starting at the entrance. There are seven aisles parallel to the rear wall in the southwest-northeast direction, extending towards the central nave. The aisles are reinforced by four support walls on four square piers and covered with lower pointed barrel vaults. The support walls extending in the east-west direction are connected to each other with pointed arches in the same direction. An opening is visible today between the third and fourth support walls, which was probably a lantern dome used for lighting the space. Traces of loading platforms, 40 cm higher than the floor, were revealed during the excavations conducted in the covered section.

The covered section was lit by seven slit windows on the eastern and the western facades, and one on the northern wall facing the central nave.

EXTERIOR

The outer walls are reinforced by two support towers on the eastern and northern walls: one polygonal tower in the northeast corner, one circular tower in the northwest corner and two square towers on the southern side. Intact spouts used for draining rainwater are visible at the top of the exterior side of the eastern wall.

No mosque space has been identified in the han.

Next to the han to the south is a fountain and a bath. The bath and the fountain were built together, as the fountain supplies water for the bath. The fountain, which consists of a gutter and a trough, has been repaired many times and has lost its original architecture. The bath was small in scale. It is believed that it was built at a later period than the han. Today only a small section of the space used as the caldarium (hot room) remains today. Traces of two spaces used for heating and a water tank in the northern part can also be detected.

BUILDING MATERIALS

The han was built with smooth and rough-cut stones, rubble stone and spolia pieces.

The walls of the han were built by infilling small rough-pitched stones and mortar between two smooth-faced stones. The stones used in the piers and top covering are smooth-faced. Reuse spolia materials can be seen on the southern wall of the crown door, as well as in parts of the covered section. These spolia pieces are from the nearby ancient city of Cremna.

DECORATION

All decorative attention here is directed to the portal of the covered section. The stone carvings on the main portal are noteworthy. The crown door of the han is approximately one meter deep and its upper part has unfortunately suffered a loss of material, as have the four borders surrounding the arch above the crown door. The door is framed with a series of borders of geometric and floral decorations. Each border has a different pattern: t-shaped elements, nodules, grids and six-pointed stars. There are two small columns on each side of the door, with capitals composed of two rows of pointed acanthus leaves. Above each a column filled with a carved rosette filled with rumi split-leaf foliate scroll elements in the center, with lotus flowers in four directions uniting with the rumi stems to create an eight-pointed star, similar to those seen on the courtyard crown door of the Karatay Han. The side columns have acanthus leaf capitals intermingling with lion heads. Over the column capitals is a rosette with palmettes and lotus leaves.

The portal consists of a protruding iwan with a vaulted niche in the shape of a segmented scalloped shell. The design of this portal constitutes a radical variant from the previous han portals. At the base of the arch is a figure of a side profile of a lion cut in very high relief on each side. However, it appears that the decoration program of the door was not completed, either due to a construction issue or to the political turmoil of the period. A solar symbol with a human face embellishes the backs of the lions. This lion and solar figure, known as the şir-i hurşid, is the armorial symbol of the Sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II, and is a variant of those seen on Seljuk coins minted during his reign.

The sun is believed to have been used by the Sultan to refer to his Georgian wife. The use of these two symbols has been interpreted as the amalgamation of the zodiac signs which represent the sultan's birthday or the date of his marriage. A similar human-faced sun can be seen on the Cizre Bridge built in 1164. The sun with a human face and the two confronting lions on the pediment of the crown door are two noteworthy examples reflecting the Central Asian cultural heritage of the Seljuks. Other decorative elements on the portal include arabesques.

DIMENSIONS

Total area: 2,750 m2

Area of covered section: 1120 m2

Area of courtyard: 1300 m2

The Incir Han is one of the smaller hans of the Seljuk group.

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

Little more than the foundations remain in the courtyard. The rest of

the han is in good condition.

The structure had not undergone any repairs until recently. Excavations of the

courtyard were carried out under the leadership of R. H. Unal and the Museum of

Burdur began in 1992. The excavation work has resumed since 2000, and all the

spaces of the courtyard have been identified in detail, as well as the loading

platforms in the covered section and the flooring system, including the pool.

Among the findings made during the excavations were several small pieces dating from the Byzantine, Seljuk and Ottoman eras, notably a series of coins dating from the era of the Seljuk Sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II; however, the majority of them could not be specifically identified due to corrosion. Other coins were found dating from the 13th to 19th centuries, which indicates that the han was in use for this period. In addition, the remains of a pool have been identified in the southwest corner, around the inner walls of the covered section, which is believed to be part of the original construction.

The excavation work now completed, the structure is ready for restoration. There are plans to turn this very handsome han into a tourism venue.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Altun, Ara. An Outline of Turkish Architecture in the Middle Ages, 1990, p. 199.

Bektaş, Cengiz. Selçuklu kervansarayları, korunmaları ve kullanılmaları uzerine bir öneri = A proposal regarding the Seljuk caravanserais, their protection and use, 1999, pp. 60-61. Ekinci, H. Incir Han 2014. Yili Kazi Raporu, 2016, p. 137.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 1, pp. 320-325.

Demir, Ataman."Anadolu Selçuklu Hanları. İncir Han", İlgi, 56 (1989), pp. 8-12

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, p. 57; pp. 366-377.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961, pp. 107-110, no. 29; vol. 3, pp. 152-153.

Erkiletlioğlu, H. & Güler, O. Türkiye Selçuklu Sultanlara ve Sikkeleri, 1996, p. 123.

Erten, F. Antalya Vilayet Tarihi. Istanbul, 1940.

Ertuğ, Ahmet. The Seljuks: A Journey through Anatolian Architecture, 1991, pp. 79-80.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 504.

Hillenbrand, R. Islamic Architecture: Form, function and meaning, 1994, fig. 6.53, p. 553.

Karpuz, H. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, vol. 1, 2008, pp. 215-218.

Lanckoronski, K. Städte Pamphyliens und Pisidiens. Vienna, 1890-92, vol. II, p. 188, fig. 154.

Önge, Mustafa. "Caravanserais as Symbols of Power in Seljuk Anatolia. In Jonathan Osmond and Ausma Cimdina (eds.) Power and Culture: Identity, Ideology, Representation. Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2007. pp. 49-69.

Özergin, M. Kemal. Anadoluda Selçuklu Kervansarayları, Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 152, n. 53.

Redford, Scott. "The Inscription of the Kirkgöz Han and the problem of textural transmission in Seljuk Anatolia", Adalya 12 (2009), pp. 351-352.

Redford, S. Reading Inscriptions on Seljuk Caravanserais. Eurasiatica 4, 2016, pp. 221-233.

Riefstahl, R. Meyer. Turkish Architecture in southwestern Anatolia, 1931, p. 69.

Rott, H. F. Kleinasien Denkmaler aus Psidien, Pamphylien, Kappadokien und Lykien, 1908, p. 21.

Sarre, F. Reise in Kleinasien. Sommer 1895. Forschungen zur Seldjukischen Kunst und Geographie des Landes, 1896, pp. 84, 107.

Schoenborn, Julius Augustus. Einige Bernerkungen über den Zug Alexanders durch Lycien und Pamphylien, 1849, pp. 20, 27.

Tavernari, Cinzia. Stones for Travellers: Notes on the Masonry of Seljuk Road Caravanserais. In Blessing, Patricia and Rachel Gosgarian, eds. Architecture and Landscape in Medieval Anatolia, 1100-1500. Edinburgh, 2017, pp. 68-73, fig. 3.2, 3.3, pl. 5.

Unal R. H., Burdur-Bucak Incir Haninda, X Vakif Haftasi Kitabi, 1993.

Ünal, Rahmi Hüseyin. İncir Hanı 1993 Çalışmaları, Sanat Tarihi Dergisi, VIII, E.Ü.E.F., İzmir, 1996, pp. 117-129.

Ünal, Rahmi Hüseyin. Incir Han Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı Publications, 2007, pp. 304-319 (includes bibliography), p. 504.

Eravşar, 2017. p. 369; photo I. Dıvarcı

|

|

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 375; photo I. Dıvarci

|

|

|

High-relief sculptures of lions with solar symbols on the main portal

|

Detail of scalloped vault over the main portal

|

|

Cells in covered section; roof of middle vault now collapsed

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 387; photo I. Dıvarcı

|

|

plan drawn by Erdmann prior to the survey of the courtyard of the han in 1993 |

|

|

|

|