The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

Chapter 45

The Shutterbug Priest

The following chapter is an extract from the book of essays by Katharine Branning

on the history and culture of Tokat, Turkey, entitled

Tokat Ancient, Tokat Green (publication forthcoming).

|

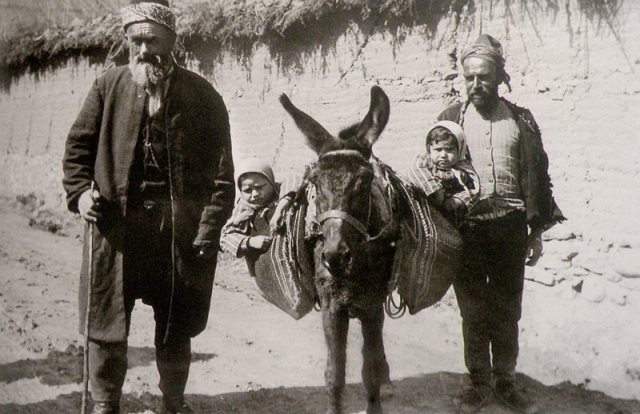

Pontic men and children: photo by Guillaume de Jerphanion (Archives of the Pontifico Istituto Orientale)

Of the many foreign travelers who came to Tokat in the past, one stands out from all the rest. This one is distinctive, not due to the vivid descriptions in his writings, but for his images, more poignant and revealing than those of Van Lennep. This traveler left a series of photographs and detailed maps which allow us create a visual understanding of the Tokat world of his time. I call him the Shutterbug Priest, but his real name was Père Guillaume de Jerphanion.

Guillaume de Jerphanion (1877-1948) was a French Jesuit priest. He was more than a priest, for in good Jesuit tradition, he was well-educated and multifaceted: a man of the cloth, certainly, but also an epigraphist, geographer, photographer, cartographer, linguist, archeologist and Byzantine scholar. He was the first person to have undertaken a systematic exploration and study of the cave churches in Cappadocia, about which he published several works. Above all, he was a ground-breaking shutterbug in a time when photography was still new, and a pioneering cartographer in an age when few people had any idea where Anatolia was situated on the world map. He put a human face on the Turkish people, pinpointed geographical references, and captured images of the yet-undiscovered monuments of Anatolia for the entire world.

**

Son of an ancient noble family, Père de Jerphanion was born in the scenic Var region of southern France in 1877. The young Guillaume initially wished to embark on a career in the Navy, but at the age of 16, he heard the words attributed to St. Ignatius, founder in the 16th century of the Catholic Order of the Society of Jesus, and took them into his heart: “Ad majorem Dei gloriam”: all for the greater glory of God and the salvation of man.

Cappadocia may have constituted his life’s work and made him famous, but it was in Tokat that Jerphanion first discovered Turkey. Jesuits were present in Anatolia since the 16th century, but it was only in the 1880’s that their influence became firmly reinforced. They were sent by the Pope to the Pontic region to encourage the “return” of the Gregorian Armenians into the embrace of the Catholic Church, and to counterattack the increasing influence of the American Protestant missionaries established in Anatolia. The Jesuit “Mission of Lesser Cilicia” founded schools in the cities of Merzifon, Amasya, Tokat, Sivas, Kayseri and Adana which operated from 1881 to 1924. The Jesuits found their place in this religiously and ethnically-complex area, and by the time Père de Jerphanion arrived in Tokat in 1903, there were 36 Jesuit priests and 12 brothers working in Anatolia.

**

The Jesuit order, dedicated to the vocation of teaching, mandated that all noviates teach abroad as one of the steps required to become an ordained priest. Jerphanion came to Tokat in 1903 to teach math and physics in the school that had been established by the Jesuits in 1881. He was also charged with the subtext of trying to convince the young Armenian students in the school to embrace Catholicism. He learned to speak both Turkish and Armenian quite quickly, two of the ten languages he mastered, and in later years he revealed that it was in Turkish that he felt he expressed himself best, even before his native French. When he arrived in Tokat, he found a primary school and a high school for boys, each with a courtyard and a garden. There was also a primary school and a high school for girls, as the Jesuits were assisted in their educational work in Tokat by an order of nuns from Nîmes, the Oblates de l’Assomption, with whom Jerphanion must have shared the same lilting singsong accent of southern France.

In all, there were 184 students in their school, far more than Van Lennep had in his Protestant mission. As was the case for the Americans, all did not always run smoothly: there was the lack of adequate infrastructure, materials and men, as well as inevitable clashes with authorities and hostility from local groups, yet the Jesuits persevered and became involved in the community which allowed them to spread their influence outside the classroom walls – even onto the hilly terraces where they taught locals the fine points of French viticulture. The Jesuit schools proved more effective than the American ones for several reasons. They offered both daytime and evening classes. Although the day classes were tuition-based and filled with students from Catholic and Orthodox Armenian and Greek families, the free classes in the evenings attracted the Muslims, and many Turks sent their children to them. An important motivation was the attraction of Western ways, as strong in Turkey then as it is now. The Jesuits also organized a wide range of extracurricular activities, such as musical education, theatricals and singing, which proved wildly popular with the students, and these theatrical performances became the subject of many of the photographs taken by Père de Jerphanion. The nuns also organized workshops on carpet weaving in order to teach young women a profession. An additional, but subtle, reason for the success of the Jesuit venture was la belle langue française: it must be remembered that these were the days when French reigned as the lingua franca of the upper classes and in the commercial world, and the Jesuits were able to use this card to advance the influence of their schools.

Yet, it was above all their medical assistance which earned their respect among the local population. An important activity of the Jesuits consisted in the opening of free clinics, which offered precious assistance to those who had no money for basic health services, especially during the outbreaks of cholera which were all too frequent during these times, notably in the summer of 1894. They rode from village to village to provide assistance and were well-received, and one Jesuit relates in a letter that a villager confessed to him: “You are different; you are like the tin-plated bowls that one puts on public fountains: you are of service to the poor. May Allah put you in Paradise second after Muhammad!”, a poignant remark in view of the fact that one Jesuit priest did die in Tokat due to his ministrations to cholera victims. It was probably here on the village back roads of Tokat that Père de Jerphanion learned the true humility of Jesus, by serving all, sick and in good health, rich and poor, Muslim or Christian.

Père de Jerphanion must have been busy those first years, discovering the region and its people, wrestling with student projects and lesson plans, and learning languages. Yet nothing daunts a Jesuit, and he sought to fill his eager mind with all it could absorb. It was in Tokat that he began his first research missions in archaeology and geography, using photography for scientific documentation. From Tokat, he took side trips to Niksar, Turhal, Amasya and Sivas, where the Jesuits had established a school as well in 1904. These trips allowed him to become acquainted with the people and also the region in greater detail, and provided him much stimulation and material for his budding parallel career as photographer, cartographer and archaeologist. This region was not often visited by travelers, and his reports to the review Orientalia Christiana in Rome provided noteworthy information. The young priest got his Turkish bearings by first looking at the Seljuk monuments which amply fill the streets of Tokat, Amasya and Sivas. He was a groundbreaker, for the seminal works by Western scholars on Islamic art had yet to be published.

**

It was during his time in Tokat that Père opened his lens angle wider and took on another impressive activity. During his stay in Tokat, Père de Jerphanion produced, with the support of the French Society of Geographers, the first large scale map ever to be drawn of the Pontic region. He returned to Tokat after his ordainment for additional research, and produced his famous map of the middle basin of the Yeşilirmak River which was published by Henry Barrère in Paris in 1913. The maps were on a scale of 1/200,000 and comprised four sheets: one each for Amasya, Niksar, Sivas and Zile. Get out a magnifying glass and look closely at these sheets, and you will see a little letter in parentheses next to each village, denoting the nationality of the citizens living there: T=Turkish, A=Armenian. G=Greek, C=Circassian, K=Kurdish and QB = Kizilbaş Alevi Turcomen. In addition, he duly noted on each map the vestiges of the monuments of antiquity and of the Seljuk era. These maps are dead-on accurate, and beautiful to behold. This was a labor of love and a symbol of the immense respect Père de Jerphanion held for the region of Tokat.

**

In 1907, as his missionary period in Tokat was nearing its end, little did Père de Jerphanion know that his true involvement with Turkey was on the verge of being fixed on his soul as clearly as the images on his silver glass photography plates. Before returning to Europe for his final theological studies and ordination, Guillaume de Jerphanion made an excursion to Cappadocia with a fellow Jesuit, Père Joannes Gransault, whose duties called him to travel there. Père de Jerphanion did not choose to come to Turkey; it was decided for him by his superiors, but the wide angle lens of life works in strange ways – call it ordained destiny, if you wish – for it was on this trip that he discovered what was to become his life’s work. Thunderstruck by this region and its religious mystery, he never turned back from that first impression of “valleys in the searingly brilliant light, running through the most fantastic of all landscapes”. He was now committed to Turkey for the rest of his life.

From the narratives of the first travelers to the region to the organized tours of today (complete with hot air balloon rides and wine tastings), phantasmagorical Cappadocia has never ceased to amaze explorers, adventurers and visitors, fascinated by the alliance of stunning landscapes and monuments. The descriptions of the first known European voyager to the region, Paul Lucas, who was commissioned by King Louis XIV of France to carry out a research tour in Anatolia at the beginning of the 18th century, were received by his contemporaries with incredulous doubt, and the monuments and sites he described fell quickly into oblivion. The exploration of Cappadocia was to be taken up again a century later, as related in the travel accounts of Charles Texier, William John Hamilton and William Francis Ainsworth. Yet, Cappadocia remained ‘lost’ to the Western world until Père de Jerphanion, riding on horseback through central Anatolia, happened upon those valleys of light, leading to his research which introduced this region to the world. Cappadocia was now ‘discovered’ and on the map.

Père de Jerphanion saw more than spectacular lunar landscapes: he was moved by the testimony of faith he found in the cave churches carved in the soft tufa rock formed by the lava spewed by nearby volcanic Mount Erciyes. Christians escaping Roman persecution arrived in this area in the 4th century and set about carving domed churches with vaulted ceilings from the friable rock. They adorned the rocky ceilings with colorful and dramatic frescoes painted from natural ochre tints. Some of the simple frescos date to the 8th century, but it is the ornate Byzantine frescoes of the 10th-13th centuries that are the most noteworthy. Père de Jerphanion immediately set to work to study the territory, epigraphy, pictorial decoration and architecture of this unique area.

After this life-changing trip, Père de Jerphanion returned to Tokat, packed his bags and returned to Europe to complete his theological studies – it is a long road to become a Jesuit priest – and was ordained in August, 1910. Yet those valleys of brilliant light pulled him back to Anatolia, and soon after his ordainment, he returned to Turkey for more field work from 1911-1913. The campaigns during these two years resulted in the monumental publication on the cave churches and their decoration which marked the first scientific study of Cappadocia. The rich harvest of maps, sketches, photographs, and watercolors proved to be a revelation to the art history world, and constituted one of the most important manifestations of the past 50 years in the field of Byzantine art. Between 1925-1942, he published, in 2 volumes of text and 3 volumes of plates, his magnum opus: “Une nouvelle province de l’art byzantin, les églises rupestres de Cappadoce” (A New Province of Byzantine Art: the Cave Churches of Cappadocia). The naïve paintings of saints and biblical scenes of the cave churches of Cappadocia came alive for scholars, and Père de Jerphanion was the first to inventory, classify and situate them in the context of Byzantine art. His illustrious work made these churches celebrated – and no doubt led to their being classed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

During his field work, this devoted Jesuit priest celebrated mass every morning at 5 am, before the digging and drawing of the day commenced and the oppressive heat rose in waves. I have difficulty imagining how Père de Jerphanion withstood the brutal heat of this region dressed in his heavy black cassock, but he and his team were determined. It must have gotten extremely dusty, that cassock, yet in that dust Père de Jerphanion found the calling in which he could best serve the greater glory of God. For the rest of his life, Père de Jerphanion continued to research and write on Christian archeology of antiquity and the Middle Ages, of which Asia Minor held a major role. He was appointed as researcher and professor at the newly-created Pontifical Oriental Institute in Rome in 1917, a post he held until the end of his life; he was a frequent lecturer at international conventions, and a scholar celebrated the world over. His output of letters, articles, books and conference papers was prolific: some 210 published pieces over the span of his career, a life’s vocation that all started in the green hills of Tokat, in the shadow of a castle perched on a rock.

**

We can marvel at the reproductions of the colorful church wall paintings of Cappadocia in his books, but it is the black and white photos that Père de Jerphanion took in Tokat which reveal to us the man behind the lens. His depth of field was impressive: he took pictures, not just of the Jesuit school and of its students, but also of a wide variety of subjects of Tokat life – the countryside, city views, Seljuk monuments, interiors of houses and festivals. Looking at these photos helps us to understand a world on the brink of dramatic change: World War I and the arrival of the Turkish Republic were in the background of every shot he took.

His photographs taken in 1903-1907 are especially important, as they are the only ones that we have of this time of the monuments of Tokat. He also took many photos of the school and structures of the Jesuits. The many fine Ottoman houses of Tokat caught Père’s eye as much as they do ours today: several photos show the interior of an Armenian home, the details as sharp as what we see in many of the remaining 19th century houses in Tokat, such as the Latifoğlu Mansion. Like a tourist, he photographed the view from his window at the Jesuit headquarters; and, looking at those vistas today, it is hard to recognize any of the buildings in the distance, except for the sentinel castle on the rock and the Ali Pasha Mosque.

Père de Jerphanion loved teaching; that you can see in the touching photo of his classroom laboratory, where he instructed young boys in the mysteries of physics. His camera lens caught boys playing at recess in courtyard, throwing snowballs, running, shooting marbles and reading; so engrossed that their noses touched the pages of their books (I rather expect that this one was a staged shot…). We see students in home-stitched fancy costumes during the theatricals for the Fête du Père Supérieur or Mardi Gras. There are class photos, with one quite impressive group photo of the students amassed on the steps in front of the building, as well as an official photo of the staff. He photographed both the students of the free classes and the paying classes, with the photos showing obvious differences in clothing styles, yet the children of modest families were photographed with the same respect as those from wealthy families. Père de Jerphanion came from a family of eight siblings, so he certainly understood kids and families.

His eye and his shutter were intrigued by the Seljuk monuments in town, and he took pictures of the Hidirlik Bridge (with no buildings surrounding it!) and the façade and courtyard of the Gök Medrese, hidden behind several structures built up in front of it, since removed. There are pictures of the streets of Tokat in the snow and after a fire. He took photos of the surrounding villages, of farmers at work and relaxing on the Topçam plateau, just as they do today. He came from the countryside of France, so he understood the farmland of Turkey and did not look at it as strange or distant, and his photographs vibrate with the love of this brown earth and the life of its inhabitants. Looking at the photographs he took, we can see the Turkey that he saw and was trying to show us. Perhaps my favorite photo of all is the one where Père de Jerphanion captured a fellow man of faith: a local imam sitting on the kilim-covered floor of his simple wooden mosque, head bent over his open Qur’an on its stand. I can hear the bismillah on his lips when I lean close to the photo.

We have several photos of Père de Jerphanion as well: a thin, distinguished man with a patrician French face; ramrod straight posture, intelligent eyes, a long and neatly-trimmed beard, and a decidedly regal bearing in his black cassock and wide-brimmed floppy hat.

I am curious about the technical aspects of these photos. What kind of camera did he own? It had to have been a box camera using dry collodion process silver and gelatin glass plates, as the wide-range imaging and depth of field on the photos of monuments and landscapes is superior, and the details on the portraits are crisp with no blurring. I especially wonder where those glass plates were developed. Did he pack them up in crates and have them carried by donkey up to Samsun to be sent by boat to be developed in Constantinople, or did they get shipped all the way back to France? Or – dare I imagine – did the physics teacher develop them himself in his Tokat classroom laboratory? With Père de Jerphanion, anything was possible. I wonder where he learned the art of photography, and have come to the conclusion that he was self-taught. I think too, of the astonishing adventure of a man in a cassock hauling about a cumbersome box camera with its heavy glass plates and unwieldy tripod on horseback under the blazing sun all throughout Anatolia, in order to capture the images that would later entrance the entire world.

**

The adventure of Père de Jerphanion with Tokat had one last chapter. After World War I, all the buildings of the Jesuits were requisitioned, and Père was sent back to Tokat in 1927 to inventory the Jesuit properties and to resolve the financial restitution of this seizure of property. He found a Tokat substantially changed from the one he left in 1907. He was 50 years old this time; no longer the young man who first encountered Turkey in the waning years of the Ottoman Empire, but rather a skillful diplomat navigating some heavily-roiled waters of the early Republican period. His negotiations to procure compensation for the confiscated Jesuit property with the government of Ankara were legally complicated, but Père Jerphanion was doggedly persistent. His dealings with the Turkish officials were often problematic and his efficient Turkish lawyer died unexpectedly, leading an exasperated Père to believe on many occasions that there would never be a positive outcome to the sale of the Jesuit buildings, the release from paying back taxes and the compensation for the ensuing legal fees. He showed great patience, diplomacy, and a sound understanding of the law, and he got results. In the end, it was Mustapha Kemal Ataturk himself who signed the final Jesuit property release papers.

**

Père de Jerphanion had a twin sister, and thus, beginning in his mother’s womb, he carried dual parts in his soul. He was a man who shared two countries, France and Turkey. He was a contemplative man of the cloth and an action man in the field, a shepherd of children and a leader of archaeologists, a priest and a photographer, and a French nobleman working among Turkish peasants. This Provencal, born in the Var, the most stunning region of France, was able to recognize the beauty of his adopted country of Turkey. His eyes lifted to God, but they also peered directly at life through the lens of his camera. He was a highly influential scholar who wrote for a scientific public, but also ministered to the needs of the poor lambs of Jesus in Tokat. He lived through the two World Wars, but never lost his faith. When he came to Tokat, he was as green as its hills and unformed; when he returned to Europe, he was mature and with a solid scientific career in his hands. From the age of 26 to the end of his life, Turkey remained beating in his heart. Could I venture to say that those four years in Tokat as a young man were the most beautiful of his life? Tokat welcomed him, and he loved this land in return. For those who love Tokat, we too, are forever grateful for his map and those photos which captured the richness of this area.

Père de Jerphanion is one of the heroes in my pantheon of scholarly luminaries. I admire his faith, his rigorous scholarship, his curiosity, his generous heart, his vision, and his boundless energy. I also feel a kinship with him, for, like me, he did not choose Turkey, but it chose him. I can understand his emotion upon seeing a monument that would alter his life and spin it in an entirely different direction. My love for Turkey now constitutes such a large part of who I am as a person, that if it were removed from my inner soul, I literally cannot imagine who I would be today. Père de Jerphanion felt the same, for the land, the people, the humanity, the color and the culture of Turkey impacted him and formed his intellectual shape. He allowed his love for Tokat and Turkey to bloom without prejudice, and it gave him the courage to accept and respect the differences of our world.

We take pictures today, millions of them, easily snapped by cell phones and digital cameras, sent via twitter, instagram and flikr; so many images that at times we lose track of their importance, filing them away in apps and clouds. Yet, do we really take the time to look first at our subject before we click the button? And once the photograph taken, do we observe the details inside them; the collars of shirts, the shoeless child, the mud brick wall, the cornice edge? The photographs of Père de Jerphanion, shot with tenderness and never with disrespect or voyeurism, remind us to take the time to look closer at the world around us.

World War I and the arrival of the Turkish Republic changed the face of Tokat forever. Such emotion Père de Jerphanion must have felt when he came back to Tokat in 1926, to find his small town so transformed – were any of his students that he captured in his photos still there? I often wonder how this man of faith interpreted the events that took place in the years after he left Tokat as a young teacher. I especially wonder what his camera would have captured had he been in Turkey during the war years. We don’t have such photos, but we can hear his melancholy about the changed Tokat in these words, written when he returned to the city in 1926:

“Tokat! With emotion I revisited the places where I had formerly worked; here in this land that captured my heart so long ago. I could recognize in the distance the same landscapes, the same valleys and mountains, forever engraved in my memory. But alas, it was only the backdrop I could revisit, for the rest of the setting was empty. Those same mountains now look upon a completely different scene.”

My favorite publication of Père de Jerphanion is the Mélanges d’archaéologie anatolienne (1928), as it depicts both antique, Byzantine and Seljuk monuments, all in one volume, which reinforces the depth of the cultures that have lived in Turkey. I believe that Père de Jerphanion was trying in this book to help us understand that history is a continuum and that we must honor the heritage of every era and keep our faith and belief in each one, forgiving, like Jesus, of turmoil and mistakes made along the way. The service of God took Père de Jerphanion to the green Tokat hills and beyond to the fawn plains of Cappadocia, and now we are all richer for where his love of Anatolia takes us. Above all, we are grateful for the lessons he has given us about always keeping in focus the dignity of the fellow man we see on the other side of the camera lens of our lives. Ad majorem dei Gloriam.

|

|

|

Guillaume de Jerphanion (1877-1948) |

©2001-2025, Katharine Branning; All Rights Reserved.

8