The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

KIRKGOZ HAN

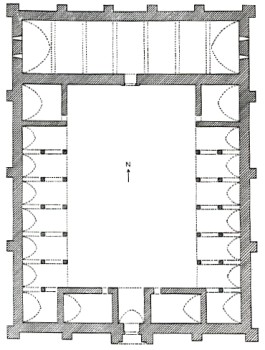

The hot climate of Antalya necessitates a twist to the classic covered section plan: all focus is on the open courtyard, vast as a playing field, with a narrow horizontal covered section located behind it.

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.2, p. 132 portal before the restoration |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 512; photo I. Dıvarcı portal after restoration in 2007 |

|

Main portal arch with inscription plaque (kitabesi) |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 507; photo I. Dıvarcı overview before restoration |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 510; photo I. Dıvarcı overview after restoration |

|

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

|

|

inscription plaque |

|

detail of column at entry |

plan drawn by Erdmann |

|

View from courtyard looking back to main entry |

|

View from main entry looking into immense courtyard and towards the small entry door to the covered section |

|

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 510; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 509; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 508 |

DISTRICT

07 ANTALYA

LOCATION

37.111444, 30.585572

The

Kirkgöz

Han is located 24 km northwest of Antalya on the Burdur Road. Take the turnoff

for the village of Yeniköy, which is approximately 10km

from the main highway. The han is approximately 10km past the village, to the

left of a brick factory. It stands beside Kırkgöz springs on the old road from

Antalya. The han is 300m to the right of the

Çubuk

Gorge, in a scenic setting of stunning beauty.

It is the first han north of Antalya on the Antalya-Burdur Road (Evdir, Incir and Susuz), connecting the coast with the interior. The old caravan road passed directly to the east of the han, and then continued north towards Burdur via the Evdir Han, the Döşemealtı pass to the Susuz Han and then on to the İncir Han near Bucak, Burdur.

NAMES

The han took its name from the nearby water sources, called the Kirkgöz ("Forty Springs") by the locals. Kiepert marked the han on his map as the "Kirk Han". Kiepert and Rott mention a han on this road called the Cibuk Han, which must have been this one.

DATE

1237-46

Dating is according to the inscription of 6 lines carved on a single block of stone set above the southern entrance door. This inscription is the longest building inscription of any surviving Seljuk han. Although the date included on the last section inscription is fragmentary (it cuts off the date; listing only the beginning of the date (read by scholars as either 1 or 3 or 13) without giving the month and year), it provides both the name of the sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev (r: 1237-46). This han was most probably built at the same time as the Eğirdir, Incir and Susuz Hans, for this caravan route was of capital importance for Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II. They were probably built before 1243 (Battle of Kösedağ), in part to facilitate the transport of goods such as alum from the mines around Afyon to the port of Antalya, where it was then exported to Europe. Alum, an essential mordant for dyeing wool (it fixed the dye to the wool so the colors would not run) and in tanning, was a particularly important export for the Seljuks. The cloth of the robes of the medieval Kings and Popes of Europe were woven with thread treated with Turkish potassium alum. The alum mines of Egypt were almost exhausted by the start of the 13th century and thus the alum mines in Seljuk Anatolia became important sources for alum. The tax revenue on alum and the monopoly of its export belonged to the Seljuk Sultanate. History records show that for one year this alum monopoly was sold to both a Genovese merchant and a Venetian merchant, who bitter trade rivals. They then jointly ran the alum monopoly in the Seljuk territory. In the 13th and 14th centuries, caravans of camels loaded with alum moved down the road between these hans, from han to han until they reached the port of Antalya where the alum was loaded onto ships.

REIGN OF

Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II

INSCRIPTION

The inscription plaque of 6 lines above the main portal of this han has attracted much attention due to its length and content, and the various readings of it by scholars. It is carved on a single block of limestone, and is the longest building inscription of any Seljuk han. It provides significant information and insight into the reign of Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II, notably in three points. 1) It assigns a function to the building, as a ribat, which is rare in Islamic architecture. 2) Secondly, it imparts additional information about Seljuk regalia, the signs of royalty the sultan wore when he traveled. 3) Lastly, if the reading of Redford is accepted, it provides information about a little-known member of the Seljuk dynasty, Ismat al-Dunya wa'l-Din, the first cousin and third wife of Giyaseddin's father, Alaeddin Keykubad.

There are even traces of the original red paint which covered the letters, which are executed in rather careless carving. This inscription, like the one at the Sarafsa Han, is carved out of limestone and not marble as is generally the case. This inscription has proved difficult to read, due to the difficulty of both its epigraphic style and grammar, as well as the novel content. It has been the subject of several interpretations and much discussion. Paul Wittik was the first to publish this inscription, but he was basing it on notes and a copy of the inscription made by Fikri Erten, the then Director of the Antalya Museum. His translation included the date of the month, the function, and the name of the sultan. The historian Scott Redford proposes a new reading, with the transcription of the text as follows, with line 5 as an interpretation of the patron not seen by other scholars:

1) The construction of this commissioned, endowed, secure ribat was ordered for all

2) peoples residing in it, and travelers from it towards the east of the world and its west, in the days

3) of the state of the most great sultan, God's shadow on earth, sultan of the sultans of the horizons, possessor of the crown and the banner [and]

4) the belt, Ghiyath al-Dunya wa'l-Din, father of victory, Kaykhusraw, son of Kayqubadh, may God extend to eternity his sultanate, [by] the exalted lady,

5) queen of the climes of the world, Ismat al-Dunya wa'l-Din, pearl of the crown of nations, may God make profuse His favor in good things

6) on her property, and accept from her what he built her [sic], and extend to her in both realms (this world and the next) what will make her whole, in the year 13.

His reading of this inscription furnishes rich and distinctive details about both the han and its patron. The second line of the inscription bears the only known definite attribution of the functions of the building as a caravanserai, or resting place for travelers. The inscription states that this ribat was a place of accommodation for travelers from the east to the west for the first time. Line 3 is again unusual as it indicates the only known mention of the regalia of the sultan, to wit: crown, banner and belt, which were before this unknown among the Seljuk regalia of power. Yet it is line 4 and 5 that are the most intriguing, for they mention an "exalted lady", the Ismat al-Dnnya wa'l-Din. She is known by one other inscription, dating to the reign of her husband, Alaeddin Keykubad I, from the Çarsi Camii in Uluborlu. This inscription dates from 1232, and describes her as a "malika", or queen. This inscription was removed from the mosque and taken to the Halk Eğitim Merkezi after a fire in 1909. This woman was the wife of Alaeddin Keykubad I, who may have married her after he took Erzurum from her brother Rukh al-Din Jahanshah, in 1230. Her father, Mughith al-Din Tughrulshah, was Alaeddin's uncle, making the couple direct first cousins. She is not the mother of the Sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II (that was Mahperi Hatun), yet she appears to have been allied in some way with him, but the exact nature of the relationship is unclear. Due to the similarity of this inscription with the fragmentary inscription of the ruined Derebucak Han, it is believed that this woman was the patron of both hans.

Other scholars (Yursasver and Uysal) translate this inscription differently. They find no mention of this Exalted Lady, and state that the inscription mentions only Sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev:

1) The building of this ribat, the poor....wretched traveler

2) Tired compatriot, guest with an inner peace, peaceful with your possessions, no matter how many times having lost in trade, generous...

3) His magnificent, great Sultan...Unique to Allah, who knows everything, owns everything, everything is particular to him.

4) The son of Keyhüsrev and Keykubad, great, magnificent sultan, the main pillar of the faith and the world, Giyaseddin

5) The owner of all, knows all, magnificent...

6) Acceptance is a manner of the state...Goods and morality has he, if he is faithful, blessings to Giyaseddin, thirteen....

This reading of the inscription firmly places the patron as the Anatolian Seljuk Sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II. Although the building date is listed in the inscription, the last numbers of the date cannot be read. The numerals are either 1 and 3 or 13; however, it is not certain. This han was most probably built at the same time as the Eğirdir, Incir and Susuz Hans, for this caravan route was of capital importance for Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II.

PATRON

Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev

II ; perhaps in collaboration with Ismat al-Dunya wa'l-Din, the first cousin and

wife of Giyaseddin's father, Alaeddin Keykubad.

Despite the differences in the readings of the inscription, both firmly place the patron as the Anatolian Seljuk Sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II. Although the building date is listed in the inscription, the last numbers of the date cannot be read. The numerals are either 1 and 3 or 13; however, it is not certain. This han was most probably built at the same time as the Eğirdir, Incir and Susuz Hans, for this caravan route was of capital importance for Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II.

BUILDING TYPE

Open courtyard (OC)

DESCRIPTION

The han faces the direction of Antalya. It was built on a terrain with a slight incline to the north. This is the third han perhaps built by Giyaseddin (Eğirdir, Incir and Susuz), but this one differs from the classical covered section open courtyard plan. The Kirkgoz Han focuses all attention on the courtyard, and only has a small, one-naved covered section to the rear, arranged horizontally. The courtyard is the dominant feature of this han, with the small, one nave covered section to the south. Although there is a covered section here, the layout is the open courtyard plan.

The Kirkgöz Han is similar in plan to its nearby cousin, the earlier Evdir Han, with its arcaded courtyard of open cells. However, in this han, a covered horizontal section is added to the rear of the courtyard. It is also similar to the plan of the Kargi han, as it is believed by Erdmann that the room situated to the right rear of the courtyard served as the mosque.

Courtyard:

The vast central courtyard (33 x 52 m) is almost three times larger than the covered section. There is an iwan in the southern wing of the courtyard past the entry door. On each side of the iwan is a rectangular room with a flattened arch over its entrance and covered with a barrel vault. These rooms probably served as rooms for the guards. They are entered by small doors, covered by roughly-constructed, slightly pointed arches. A water canal was found during the excavations in the eastern room.

The courtyard is surrounded on the eastern and western sides by an arcade of 6 open cells on each side, supported by belt courses in the east-west direction on two piers. Each arcade ends to the north with a large, closed room, the same depth as the arcades but covered with a barrel vault in the east-west direction of a wider and higher span. The covered room on the right rear of the courtyard may have served as the mosque (as in the Kargi Han). There are no window slits on the outer faces of the arcades. No bath has been noted.

The crown door leading into the courtyard is more richly decorated than that of the covered section. It included a flattened arch with interconnected voussoir stones, and engaged columns with simple cubic capitals on each side. The arch encloses a deeply recessed niche covered by a short, pointed arch vault, marked outside by a twice-recessed ornamental arch. An inscription plaque is located in the tympanum of the crown door, set in a rectangular frame.

During the restoration of 2009, the opening of a cistern beneath the floor level of the courtyard and the remains of a pottery kiln in the southeast corner were uncovered.

Covered section:

The narrow covered sections one single long nave. It was built parallel to the slope is of a higher elevation than the right and left sides of the courtyard. It is accessed via a doorway topped with a low arch. It is covered with a single barrel vault in the east-west direction, divided into seven sections by 6 flat rigs. The barrel vault was supported with six equally-spaced ribbed arches. As such, the covered section here features with the Kargi and Şarapsa Hans. The covered section measures 11 x 60m. Several sections of the loading platforms can still be seen at the entrance to the covered section.

This covered section is entered by a very small door and is lit by very narrow slit windows in the east and west walls. In addition, there are lantern hole openings for light in the middle of the arches of the vaults.

The crown door of the covered section is located in the middle of the northern wall and is plain round arch surmounted by a flattened arch. There is no inscription plaque above the door to the covered section.

EXTERIOR

Square support towers are located in each external corner and four rectangular buttresses are equally spaced on the northern wall of the building.

Three rectangular support towers are equally spaced on the east and west exterior walls of the courtyard and a square tower is placed at each corner. Each side of the crown door leading into the courtyard is fitted with a rectangular support tower.

BUILDING MATERIALS

Smooth-faced stones were used in the crown doors, arches, slit windows and towers. The stones of the portal are of finer quality and are better hewn than the walls. The walls are clad on both sides by heavy rectangular blocks of dressed stone and are filled with rubble and mortar. Large stones of different sizes were used for the foundations. The walls show an impressive quality of workmanship. Reuse spolia material has been placed at the top of the entrance door of the courtyard. Some of these stones, found during the repairs made in 2007, include inscriptions in Latin. Mason marks can be seen on stones on various parts of the building.

DECORATION

The han has sparse decoration. There is no carved decoration on the entrance portal, in contrast to the Incir, Evdir and Susuz Hans, which have magnificent crown portals. In addition, the building inscription is not carved in the customary marble, but in limestone.

Despite the simplicity of its decoration, this is a dignified and impressive han. It is larger, but more simply built, than the Incir, Evdir and Susuz hans which have crown portals. This han resembles more the other southern hans attributed to Giyaseddin, the Sarapsa and Kargi hans, which also lack an elaborate decorative program. These hans may have been built after the Babai revolt of 1241 and the defeat of the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243, when the Sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev faced challenging events which placed his reign in disarray. After 1243, it would appear that the Sultan spent much time in the area beyond the Taurus Mountains, most certainly seeking refuge from the Mongols in this part of the realm farthest from them.

DIMENSIONS

3,000

m2

The courtyard measures 51 x 49m and the very small covered section 15 x 49m

Much like the courtyard of the Evdir Han, the size of the courtyard of the

Kirkgoz Han is vast (33 x 52m) and gives the

impression of a military campground.

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

The han is in good condition, and the portal is intact. For many years the arcades were used as a shelter for cattle and sheep, and the courtyard served to perform veterinary procedures on the herds. It was completely restored in 2007. Excavations were carried out in the courtyard during the restoration, at which time a sunken bread oven (tandir) was found. Unfortunately, this renovation has been criticized for not respecting the original fabric of the building. Worms of new bright yellow mortar now cover the outer walls of this 13th century building, totally disrespectful of the original Seljuk mortar and the surviving Seljuk plaster on the walls, which is quite different in composition, color and texture from this modern plaster and mortar. The roof of the covered section has been clad with reinforced concrete, and, as such, the original elements have disappeared.

The han is now used for special meeting and tourism events.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Altun, Ara. An Outline of Turkish Architecture in the Middle Ages, 1990, p. 199.

Aslanapa, Oktay. Turkish Art and Architecture. New York: Praeger, 1971, p. 174.

Bayrak, M. O. Türkiye Tarihi yerler kılavuzu, 1994, p. 78.

Bektaş, C. Selçuklu Kervansaraylari, Korumalari ve Kullanilmalari Üzerine Bir Öneri = A proposal regarding the Seljuk caravanserais, their protection and use. Istanbul, 1999, pp. 66-68.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 1, pp. 189-191.

Blessing, Patricia. Rebuilding Anatolia after the Mongol Conquest: Islamic Architecture in the Lands of Rum, 1240-1330. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2014. (Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies; 17), p. 175.

Demir, Ataman, "Anadolu Selçuklu Hanları. Kırkgöz Han", İlgi, 54 (1988), pp.17-20.

Duggan, T. Mikail P. A warning to the Minister of Culture and Tourism: So-Called restorations are destroying seven hundred years of Seljuk heritage. Turkish Daily News, 8 Sept. 2007.

Durukan, Aynur. Selçukluar Döneminde Ticaret Hayati ve Antalya. Antalya III. Selçuklu Semineri Bildirileri 10-11 Şubat Valiliği, Antalya, 1989, pp. 51-59.

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 507-514.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961. Vol. 1, pp. 179-181, no. 56.

Karpuz, Haşim. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, vol. 1, p. 131.

Kiepert, R. Karte von Kleinasien, in 24 Blatt bearbeitet, 1902-1916.

Kuban, D. Selçuklu Cağinda Anadolu Sanati, 2002, p. 241.

Özergin, M. Kemal. "Anadolu'da Selcuklu Kervansaraylari", Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 155, n. 72.

Redford, Scott. "The Inscription of the Kirkgöz Han and the problem of textural transmission in Seljuk Anatolia", Adalya 12 (2009), pp. 347-359.

Redford, Scott. Paper, Stone, Scissors: Ismat al-Dunya wal-Din, Ala al-Din Kayqubadh, and the Writing of Seljuk History. In: Peacock, Andre C.S. and Yildiz, Sara Nur (eds.) The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Mediaeval Middle East. London, 2013, pp. 151-170.

Redford, S. Reading Inscriptions on Seljuk Caravanserais. Eurasiatica 4, 2016, pp. 221-233.

Riefstahl, R. Meyer. Turkish Architecture in southwestern Anatolia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931, fig. 118-119, pp. 64-65.

Rice, Tamara Talbot. The Seljuks in Asia Minor, 1961, p. 206.

Taşkiran, Zehra Fürüzan. Antalya Çevresinde Yer Alan Selçuklu Hanlarindan Evdir Han ve Kirkgöz Han. Antalya I. Selçuklu Eserleri Semineri, 22-23 Mayis, 1986, Antalya Valiliği. Antalya, 1986.

Ünal R. H. Antalya-Korkteli Kervan Yolu userinde Bilimeyen Uc Han. Sanat Tahihi Dergisi, 19(1), 2010, pp. 57-99.

Unsal, Behçet. Turkish Islamic architecture in Seljuk and Ottoman Times, 1071-1923. London, 1959, p. 48.

Uysal A. O., Konya-Eğirdir Güzergahinda Bazi Kervansaraylar. III. Milli Selçuklu Kültür ve Medeniyeti Semineri Bildirileri, 1993, pp. 71-83.

Yurdasever, H. Anadolu Selçuklu hanlarindan Kirkgöz Hanin değerlendirilmesi. S. Demirel Üniversitesi Sanat Tahrihi Bilim Dali, 2011, p. 34.

|

small door for entry to southern side closed rooms

|

western arcades

|

|

|

|

|

Arcade of 6 open cells on eastern side of courtyard |

western arcades |

|

entry portal with view onto entry of northern covered section across the courtyard

|

closed rooms on each side of entryway; view from courtyard looking south |

***

The following excerpt from Yes, I would love another Glass of Tea, a series of essays on Turkey published in 2010, shares an anecdote about the adventures of researching hans that the present author encountered in the 1970-80s, in the days before GPS, ready transport, digital photography and cell phones, and when most of these hans were not easily accessible.

Another time, I had difficulty locating the Kirkgöz Han, located near Antalya. A similar scenario as at the Altinapa Han show ensued when I stopped to ask directions: five Turks came running over, and started to argue among themselves, each one offering two opinions. The discussion among themselves got so heated that I began to dread the results, and sure enough, before I knew it, they got so worked up that they started pushing and shoving each other. Fearing a fist fight, I started to withdraw from the mélé, but one chivalrous knight would not leave me in the lurch. Even though his buddies didnt believe him, insulted him and even punched him, he persisted, and told me exactly how to get there, giving me very vivid landmarks to look for along the way. His unusual clarity inspired confidence in me, and off I went, from landmark to landmark (jandarma station, tree with three branches, house with the green door ) and sure enough, he was right! Only a Turk would take such pains to help a stranger, to the point of risking a black eye.