The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

SULTAN HAN AKSARAY

This han is both Turkeys and the worlds largest han and is the most magnificent caravanserai built by the Anatolian Seljuks. If you can only visit one han in Turkey, this should be the one. Important in view of its scale and the elaborate decoration of its crown door and kiosk mosque, it was built by the greatest of all the Seljuk sultans, Alaeddin Keykubad. All hail the Sultan Han of the Seljuk Empire!

|

|

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

Main portal with stalactite vault |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 445; photo I. Dıvarci |

|

detail of interlace and flower panel on entry portal |

lateral arcade of the main portal |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

inscription detail, side arcades of main portal |

|

detail of palmette capitals on entry portal columns |

|

detail, architrave with stones of alternating colors and inscription |

|

cross-vault in entry vestibule |

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p.73 |

overview of the courtyard, west arcades and the kiosk mosque |

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p.74 |

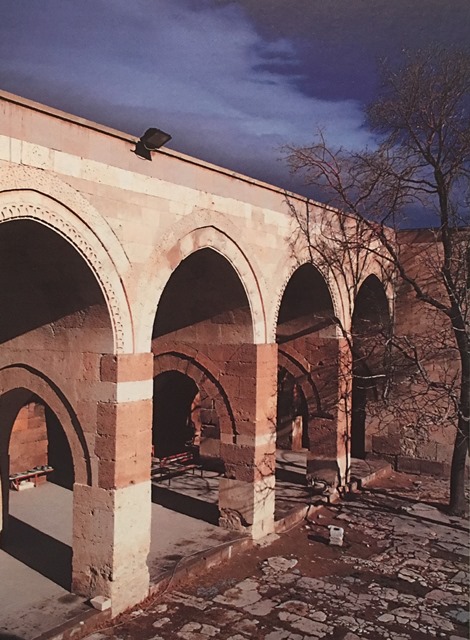

west arcades and mosque, looking north |

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p.73 |

|

eastern cells, looking south |

stairs to roof on northeastern corner of courtyard |

|

|

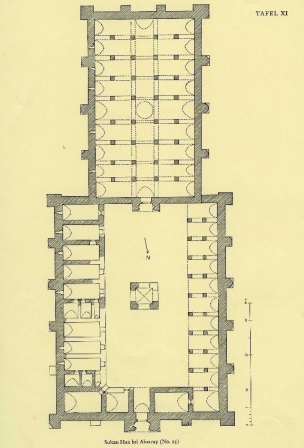

Plan of the han drawn by Erdmann |

photo by Hans Berggren, 1870-1880 |

DISTRICT

68 AKSARAY

LOCATION

38.247656, 33.546147

The Aksaray Sultan Han is located in the town called Sultanhan, on the Konya-Aksaray Road, 40 km from Aksaray, and 94 km from Konya. The town of Sultanhan is approximately 3 km south off the main highway. The han is visible from the modern highway, which passes nearby.

The Aksaray Sultan Han lies at the heart of the main caravan road which formed the most important trade network of the age, and connected the ports of Antalya and Alanya to Iran and Georgia via Konya, Aksaray, Kayseri, Sivas, Erzincan and Erzurum. This was a busy road since antiquity and was heavily used by the Seljuks, who built substantial hans along it. Ibn-i Bibi states that a messenger, sent by the Abbasid Caliph Lidinillah to Alaeddin Keykubad, used this road and stayed in hans along it it.

A historic cemetery for the war dead is located near the han.

NAMES

The caravanserai gave the name to the village of Sultanhan, which grew up around it and whose city hall is located directly across from the han.

The name of Sultan Han is mentioned both in historic sources and in the inscriptions on the han. It was referred to as the Alaeddin Keykubad Han in the texts of Ibn-i Bibi and Kerimeddun Mahmut Aksarayi, in honor of its patron.

According to the journals of Qadi Muhyiddin Abduzzahir, who kept a diary of the military expedition of the Mamluk Baybars into Anatolia in 1277, the Mamluk army defeated the Mongols at the Battle of Elbistan (April 15, 1277). Baybars marched on to Kayseri and then left the city to give the impression that the Mamluks were planning to attack the Mongol army. In reality, Baybars feared a Mongol counterattack and had decided to return to Egypt. He was far from his bases and supply lines and felt vulnerable. His army took the route northeast towards Sivas and stopped at the Tuzhisar Sultan Han. After their stay at the Tuzhisar Sultan Han, the army changed direction once again to confuse the Mongols and headed south towards Elbistan and stopped at the Karatay Han.

Many travelers and art historians visited Anatolia in different periods throughout the 19th century and mentioned the han, which is a difficult monument to miss. Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, the noted German Field Marshal, visited Aksaray in the autumn of 1838, six months before the Battle of Nizip against Egyptian rebels (June, 24, 1829, near Gazientep) where he served as military adviser to the Ottoman Army. Molke left his impressions of the han as follows:

The magnificent Sultan Han rises near a swamp. The marble crown door of this han is as high as those of the mosques in Istanbul and also has rich decorations and looks marvelous. However, you enter into a ruin from this door, an amazing one for the region. Most of the beautiful double arcades were in ruins and a brick hut among the ruins of the watchtowers is the only place where you can sit. I saw much dried camel dung under the great arches, which is the only fuel available in winter. The two beautiful peaks of Hasan Mountain guide your way in this desert. These must be old volcanoes. There is a wide crater rising like a pointed cone from inside the peak which is curved at the summit. There is another han in Obruk on the banks of a round lake, around 300 feet in diameter and approximately 150-200 feet in depth: quite a significant place for such a completely flat area. We rode the same horses for thirty-eight hours in two days and saw only two settlements until we reached Konya, it was one of the most tiring voyages I can remember. At last, when I could clearly see the domes and minarets of Konya and the many trees in the foothills of the steep mountains, I was exulted.

The British physician and geographer Ainsworth, who traveled across Anatolia between 1835 and 1837, left a quite fanciful sketch of the han and provided the following information in the book he wrote upon his return home:

We had some difficulty in obtaining permission to examine the interior of this khan, as a poor but proud Bey lived in it with his family. Luckily, we heard that he was sick and accordingly we sent our compliments, that we should be happy to do anything in our power to alleviate his sufferings. We were accordingly soon admitted to an interview, which took place on a terrace on top of the khan, and after giving the old gentleman some suitable medicine, we were allowed to roam about the ruins at our leisure, followed by the curious eyes of the Harem below. We found the building to be divided into two parts; the most easterly not very lofty but wide, and ornamented by a gateway of rich Saracenic workmanship. The interior was also richly ornamented. The westerly part was in the best state of repair, and consisted of a large covered space, supported by lofty columns and arches. It is altogether one of the handsomest khans to be met with in Lesser Asia. Over the gateway was an Arabic inscription, which was thus translated by Mr. Rassam: The exalted Sultan Alau-d-din, great King of Kings, Master of the necks of Nations, Lord of the Kings of Arabia and Persia, Sultan of the territories of God, Guardian of the Servants of God, Alau-dunya Wa-d-din, Abu-l-Fat-h, Commander of the Faithful, ordered the building of this blessed khan, in the month of Rejeb, in the year 662 (A.D. 1264)

Other travelers who visited the han were Hamilton (1842), Tschihatscheff (1867), the team of Roman Oberhummer and Heinrich Zimmer (1899), and Sterrett (1885) who photographed the han from many different angles and measured it. F. Sarre published the first and most detailed scientific study of the han and he also drew its plan.

DATE

1229

(dated by inscription)

This han hosts a veritable library of inscriptions: 6 separate ones in total. These inscriptions have been placed at various parts of the han, and provide provide precise information concerning the patron, architect, construction year and renovation information. But this han shows an interesting twist: these inscriptions are comprised of horizontal bands, not set in a framed panel which is generally the case for inscription plaques on han portals.

1 - Inscription on the right niche inside the main crown door:

|

|

The following epithet of Alaeddin Keykubad is written: The great Sultan of the Faith and the world.

2 - Inscription above the left niche inside the main crown door:

|

|

The great Sultan, the supreme commander of the Faith and of the world, Keykubad, son of Keyhüsrev, the father of Conquests. May his greatness be everlasting.

3 - An inscription ribbon which begins above the right niche inside the main crown door and wraps over the door and ends above the left niche. Again, it praises the glory of Alaeddin Keykubad.

The section above the left niche:

|

|

The section above the door:

|

|

The section over the right niche:

|

|

The building of this sacred han was ordered by the great Sultan the son of Keyhüsrev, great Padishah, the sultan of the sultans of the Arabs and Persians, the supreme master of the Faith and the world, the father of conquests, the master of the believers, the companion of the Abbasid Caliphate, Key-kubad, in the year of 626 [1229]

4 - After being badly damaged by fire in 1278, the han was renovated by the local governor Seraceddin Ahmed Kerimeddin bin El Hasan, as indicated in the inscription over the courtyard door: "This great sacred gate destroyed by burning". No information is available concerning this architect in charge of making the repairs and rebuilding the han. After this extension, it became the largest caravanserai in Anatolia. This inscription is written in the thinner and beautiful istif style. It is located under the engraved mesh composition under the covered door arch which is made of differently-colored stones.

|

|

This sacred big door was renewed, because it was ruined after a fire, by the Great Sultan son of Kiliç Arslan, Helper of the Faith and the world, in the reign period of the father of conquest Keyhüsrev May God make his reign everlasting in the year of 667 [1278], by the work of Siracuddin Ahmed, son of Huseyin, who is the trustee of the Sultan, the weak slave, in need of Gods Mercy.

5- On the top of the space between the muqarnas and arch on the main entry portal, the words El minnetullah (Gratitude to Allah) are written. This inscription was inlaid with marble pieces in different colors and sizes.

|

|

6 - Finally, the inscription on the door of the covered section gives again the name of the patron and the construction date.

|

|

This sacred han was ordered to be built by the Great Sultan son of Keyhüsrev, supreme Shahinshah, holder of the reins of the Islamic ummah, master of the Arab and Persian Sultans, sultan of all Allahs cities, protector of the people of Allah, master of the Faith and the world, father of conquests, emir of believers, witness of the caliphate, Keykubad, in the year of 626 [1229], in month of Rajab.

7 - There are two hexagonal medallions one above the other above the crown door of the covered section. On them is written the name of the master-architect: "Amele Muhammed bin Havlan (el-Dimiski)". The word "Dimiski" indicates the origin of the architect, who came from Damascus. He is known to have worked at the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya in 1220-21 as per its inscription and he probably worked as well on the Karatay Medrese.

REIGN OF

Alaeddin Keykubad I; with renovation carried out in 1278 during the reign of Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev III.

PATRON

The original patron was Alaeddin

Keykubad I, who hired an architect from Damascus named Abdurrahman bin Haflan.

The patron of the restoration of 1278 was Seraceddin bin Ahmet bin El Hasan

Kerimeddin, a dignitary at Aksaray under Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev

III (r. 1264-1278).

The foundation charter for the han does not exist. However, the han is mentioned in the texts written by Seljuk period historians, who discuss how the han was destroyed and that the door was burned down in the same struggle for the throne between the brothers Sultan Izzeddin and Rükneddin. One of these historians, Ibn-i Bibi, relates the story of the destruction of the han as follows:

They came near the Sultan to Kayseri. The crowd of his army began to increase. The people entirely supported him. Famous and brave warriors and amirs joined his army. Day after day, when he reached Keykubads camp, they started to march around it. Finally, they decided to attack Konya, and believed that they would be able to do this. On the other hand, when Sultan Izzeddin heard that Governor Şemseddin had been captured and had sided with Sultan Rükneddin, he abandoned hope of his return. His supporters became upset upon hearing this news. At that point, Felekeddin Halil and Husameddin Baycar, with a group of their soldiers, led a raid towards the Alaeddin Caravanserai which was one station away from Aksaray. When they arrived there, one group revolted against them. In response, they burned down its doors, killed some of its people and released others after seizing their assets.

According to the date in the inscription, it can be understood that the han remained damaged for long time before it was repaired, or, the repair process took a very long time. According to existing remains, the courtyard was completely renewed during the repairs made in 1278.

This han also saw some important military action. The han was under siege for two months during the conflict between the Mongol commander Irincin Noyin and a Turkish warrior rebel named Ilyas, at which time the han was destroyed a second time. Another military episode is related by the historian Kerimeddin Mahmut Aksarayi. He states that a war erupted between the Karamans and a Turkish bey named Memresh and two towers of the han were destroyed during the siege in the early 14th century. Because the towers were destroyed, the road between Konya and Aksaray became more dangerous. These damaged towers were later repaired by Aksarayi, who also served as the Minister of Public Works.

Due to its proximity to Konya, this was an important post for military purposes in addition to providing accommodation for travelers.

BUILDING

TYPE

Covered section with open

courtyard (COC)

Covered section is smaller than the courtyard

Covered

section with a central aisle and 2 aisles on each side

9 cross

vaults

DESCRIPTION

This

is the largest, but not the oldest, of the Sultan hans, and is perhaps the most

beautiful and impressive of all. Few more powerful or finely-built examples of

Anatolian Seljuk architecture exist. The most remarkable features of this

structure are the arcaded courtyard, the twin majestic portals of the entry

vestibule and the covered section, the vaulting system supported by piers, and

the free-standing kiosk mosque rising on four piers in the middle of the

courtyard. The stone decoration of the mosque and the portals is noteworthy for

its elegance and artistic mastery.

This Sultan Han has the classical Seljuk Han plan, comprised of two parts: a huge enclosed section on the south used for lodging and an open courtyard with service sections in front of it. With this han begins the era of the "big" hans: the large-scale construction projects of the Ağzikara, Zazadin, Sultan Han Kayseri, Incir, Susuz, Obruk and Karatay hans.

The han lies parallel to the road, and faces southwest towards Aksaray. The Aksaray Sultan Han is oriented north-south.

Main crown door: Few crown doors in Seljuk architecture can rival this one. It is both imposing and delicate at the same time. Standing under its muqarnas hood and looking upwards is a voyage to a Milky Way of decoration in stone. It combines artistic vision, skillful carving, and a mixture of decorative elements not often united on one single door, such as the elaborate muqarnas hood, a stone arch with stones of two different colors and a harmonious balance of both vegetal and geometric carved elements.

Entrance to the han is through an imposing portal on the north wall. The portal is 13 m high, projects out about 1.5m, and is almost 50m wide. The portal is balanced on each side by a group of three round pillars which extend 1m from the façade.

Although the crown door is partly damaged, it still maintains its original aspect. The doorway of the portal was originally topped with a pointed arch, but only one side has survived. The door is surrounded by borders of various widths, decorated with motifs placed symmetrically on both sides and a hood formed by 12 rows of muqarnas. The borders constitute a frame around the entire door. These carved side panels are formed of interlaced polygons of various sizes dotted with flowers, a curious combination of a strong geometrical element with a delicate natural motive. The borders contain different interlaced geometric elements, zigzags, circles, lotus blossoms with stems and a mesh pattern of polygons of various sizes (6, 8, 24, 32 and 64 pointed stars). A graceful arch with an intersecting ribbon decoration surrounds and crowns the stalactite vault. The door opening is framed by a column on each side with a strong zigzag pattern on the shafts, topped with capitals formed by three rows of palm fronds. The door has two lateral side niches before the entry door, which are the most extravagantly-decorated of any Seljuk han. It is in this recessed area where runs an inscription band at the base of the stalactite vault above a band of differently-colored interlaced stones (pale gray and white), similar to those seen at the Alaeddin Mosque and Karatay Medrese in Konya, and at the Zazadin Han. The two colors of stones and the patterns used here are typical of the Syrian-Zengid style that would have been familiar to the Damascene architect.

Iron clamps were used between some of the stones of the jamb to secure the blocks after the 1268 fire.

Entry iwan: Once you step through the main entry door, you enter a rectangular iwan which resembles a vestibule. It is covered with a star-shaped vault, which sets the stage for visitors to the delights of the architecture and services of this impressive han. Rooms are located on both sides of the entrance iwan, and are entered by doors in the form of niches with pointed arches. The rooms on the west are slightly larger. All are covered with pointed vaults in the east-west direction. The vaulted rooms on both sides of the entrance iwan were used as office rooms and for administrative operations (han keepers room, treasury, storage, etc.)

Kiosk mosque:

When you step into the courtyard from the iwan area, all eyes are drawn to the kiosk mosque which occupies the middle of the courtyard space like a mini-castle. The mosque of the han is a free-standing structure in the middle of the courtyard, opposite the entrances to both the courtyard and the covered section, similar to the ones seen at the Kayseri Sultan, Ağzikara and Sahipata Hans. The mosque is built on four square piers which are connected to each other with pointed arches.

The entrance of the mosque faces the crown door of the courtyard to the north. Entry to the kiosk mosque is by a set of 12 stone steps to the south side rising on the right and left sides. The side with the entrance door was completely renovated during the restoration. The original mihrab had completely disappeared, but the opening in the wall facing the direction of Mecca is considered to have been the location of the mihrab. The door of the mosque is decorated with a series of borders containing octagons, stars and triangles. A window with muqarnas and geometric elements is located in the middle of each side of the mosque. Octagons with central rosettes are located in the center of the borders. Only one of the four original rosettes between the arch and border remains today. The power and elegance of the decoration of this kiosk mosque rivals that of the portals, and is worthy of the sultan who probably worshipped here. The mosque was raised to separate it from the hubbub of animals and goods below, in order to create a clean place for worship.

Courtyard: The rectangular courtyard is wider than the covered section. It is surrounded by covered and open sections placed on three sides. The entrance to the open courtyard section is in line with the entrance to the covered section. The vast courtyard is lined on three sides with rooms used as the kitchens, bath, mosque and attendants quarters. This is a very sophisticated layout, and of special note is the fact that the courtyard contains special guest accommodation rooms similar to those seen in the Kayseri Tuzhisari Sultan, Avanos Sari and Karatay Hans.

Courtyard east side (left): The eastern wing of the courtyard contains a series of nine interconnected rooms of the same length but of different widths, each approximately 2 x 4 m. Entry is via doors with muqarnas. The rooms on this side were used for the various daily activities of the han: kitchen, refectory with carved stone console benches, baths for men and women, as well as spaces for relaxation and sleeping. Most of these rooms have slit windows to the east. Barrel vaults cover all these rectangular units.

At the northern end is a series of three rooms, one very narrow, which probably served as the baths. They are covered with pointed barrel vaults in the north-south direction. These are followed by three more rooms of the same size with entrances directly opening onto the courtyard and covered with pointed vaults in the direction of the courtyard. These could have been the disrobing rooms and furnace room of the baths.

Immediately after these rooms is another group of three rooms with vaults in the north-south direction, identical to the first bath section to the north. This is perhaps a second bath group, and could have been reserved for the special guests or women. The other 5 rooms along this side, all of the same length and approximately the same width, are covered with pointed vaults and are believed to be either the kitchens, refectory or special guest rooms.

A console ladder leading to the roof of the courtyard is set in the northeast corner of the courtyard.

Courtyard west side (right): The west side of the courtyard is comprised of an open arcade of ten sections. The pointed vaults of the sections are carried by square piers connected to each other by arches. This arcade served for storing goods and stabling animals. The high and open vaults facilitated the loading and unloading of goods. This side of the courtyard also houses latrines grouped together in a large corner space at the northwest corner. There is a deep stone channel encircling the space on the east, north and west sides. Apparently there were several individual latrines along the channel, divided by wooden partitions.

Covered section:

To the rear of the courtyard is the covered section, with another impressive crown door. The crown door of the covered section is located in the middle of the main north wall of the covered section and projects slightly from it. It comprises an elaborate decorative scheme, similar to the main entrances of other monumental buildings such as the Avanos Sari, Tuzhisari Sultan, Karatay and Ağzikara Hans. The entrance door is made of bi-color interlaced stones above a regressed arch. The crown door is in the shape of a pointed arch surrounded by four borders, each decorated with a different geometric pattern. The decorative elements consist of a chain motif, half stars, 20-pointed polygons, lotus branches and rosettes engraved with a mesh interspersed with figural, geometric elements and fish designs. The borders are connected by small columns with capital headings formed as 24-sided cubes cut with prismatic triangles at the corners and parallel-edged triangles on six surfaces. The crown door contains nine rows of muqarnas. Four rosettes of different sizes and patterns are located on each surface area between the tympanum and the surface of the muqarnas. An inscription plaque is located below the rows of muqarnas. Like the main door to the han, the interior faces of the crown door contain half-hexagonal mihrab-like arches surmounted by various decorative elements such as polygons, half-stars, braids and the Seal of Suleiman (six-pointed star) motifs. There are three rows of muqarnas above each one, with two rosettes set in each corner space of the muqarnas.

This impressive door gives access to the huge covered section containing the sleeping and living quarters for the winter months. Vast as a cathedral, the covered section comprises a central nave in the north-south direction, with a nave on each side of it. The middle nave is covered by a pointed barrel vault in the north-south direction. The central aisle, which is higher and wider than the others, resembles the nave of a cathedral. The naves are divided into nine aisles by arcades running east to west and covered with pointed barrel vaults running in the east-west direction. The naves on both sides of the middle nave run the entire length of the covered section from the entrance and are supported by two piers in each cross-nave. The loading platform system is located between the piers of the naves, except for the outermost naves.

A dome with an exterior conical cap covers the square unit at the center at the intersection of the fourth and fifth piers of the central nave. This dome is of technical interest, for it is made of pieces of stone laid helically in the fashion of a snail's shell, achieved without a mold. There is a handsome carved rope motive at the juncture of the dome with the squinches. The surfaces of the arches in the central nave carrying the lantern dome are decorated with a composition of half-stars. The four sides of the lantern dome have three semi-circular openings in the squinches, which are believed to have been added at a later date. Pendentives in the corners of the squinches connect to the dome. Light also enters the space via the four slit windows in each section of the east and west walls except for the sections opposite the support towers.

EXTERIOR

The lateral walls of the courtyard are strengthened on the exterior by 16 support towers of various sizes and shapes. The exterior walls of the covered section are strengthened by square buttresses of varying dimensions placed at undefined intervals. The support towers are not set opposite the arch lines. All of these corner and side towers give the han the appearance of a fortified castle. There is a monumental view over the surrounding plains from the roof. Flat downspouts can be seen in various points of the roof system. These downspouts drain rain and snow water to the exterior of the han and there are also downspouts which drain water into the courtyard where the mosque is located.

BUILDING MATERIALS

The han was made mostly of marble and smooth-faced travertine stone. The walls are lined in the hollow wall technique where two stones were filled with a mixture of rubble and mortar. Mason marks can be noted on many of the stones in the building.

DECORATION

The decorative program for the crown doors of the courtyard, the covered section and the kiosk mosque are a testament to the level of artistry reached by the Seljuks. The use of two differently-colored stones renders the decoration of this han quite noteworthy. Decorative carved stone elements include arabesques, blossoms, crescents, braids, trelliswork, Syrian knots, and patterned brickwork in the arches.

DIMENSIONS

Total external area:

4,500m2 (excluding towers and portals)

Area of covered section: 1,430 m2

Area of

courtyard: 2,250 m2

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

The han is in excellent condition and is run as a museum by the Turkish government. This han is a major tourist destination in Turkey, and receives 500,000 visitors each year. It was first restored in 1957. It was included in the temporary list of UNESCO World Heritage sites in 2014. Almost 2 million tourists travel on the Konya-Aksaray Road to reach Cappadocia, so the Turkish Tourism Bureau has set a goal that 1 million of them will visit this han.

This han never fell into a ruined state since it has been in continuous use since the day it was built, and was often used for military purposes and barracks due to its strategic location. It has been repeatedly repaired over the years. Soon after the han was built, it suffered a fire and was enlarged in 1278 with a comprehensive restoration in the period of Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev III, as indicated in the inscription over the crown door of the courtyard. This restoration was done by a certain Siraceddin Ahmed, son of Huseyin. Later, the support towers on the main façade, destroyed during the rebellion with the Karamanids, were renewed at the beginning of the 14th century.

The British archaeologist Gertrude Bell visited the han in July, 1907, and her photographs show the han in a well-preserved state. Closer to our days, the han was restored in 1957, and many of the damaged parts were completed. Upon comparison with the old photographs, it can be seen that some parts were not restored faithfully. In addition, this restoration unfortunately destroyed the bath and the cistern on the left-hand side of the courtyard.

The Turkish press announced on February, 16, 2017 that a 6 million Turkish lira restoration project will start on this han in March, 2017. When completed, the han will showcase traditional handicrafts including carpet weaving (the carpets of the Aksaray region are famous), copper, pottery and textile studios. It will also integrate a carpet museum, all within the han. It is estimated the project will take three years to complete. The restoration project will integrate the missing two and a half meter thick stone wall in front of the han, and will also prevent water flow from the upper storeys, as some dampness has permeated the ceiling. This restoration work is reaching its final stages (2019). In October, 2019, the han will host the International Silk Road Culture and Carpet Festival.

This han is much admired by the local people. Konyali relates that the stones of the han had been removed by villagers to build their homes. However, one of the villagers from Sultanhan collected the stones, brought them back and turned them over to the workers who were renovating the han in 1957. Blessings to his hands, as they say in Turkish, for indeed, this man has made it possible for the most glorious han ever built to continue to inspire and awe us to this day. Long live the Sultan of Hans!

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı Publications, 2007, p. 453.

Ainsworth, W. F. Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia Chaldea and Armenia. London, 1842.

Anatolias biggest caravanserai to be restored. Daily Sabah, 16 Feb. 2017.

Aqsarayi. Kerimuddin Mahmud-i Aksarayi. Selçuki Devletleri Tarihi, 1943.

Bayrak, M. O. Türkiye Tarihi yerler kılavuzu, 1994, p. 571.

Bektaş, C. Selçuklu Kervansaraylari, Korumalari ve Kullanilmalari Üzerine Bir Öneri = A proposal regarding the Seljuk caravanserais, their protection and use, Istanbul, 1999, 140-45.

Bell, Gertrude. Gertrude Bell Archives. Internet web document. www.gerty.ncl.ac.uk/, folder I, photos I195-210.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 1, pp. 108-117

Durukan, Aynur. Aksaray Sultan Hanı, Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara Kültür Bakanlığı, 2007, pp. 140-159 (includes bibliography).

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 434-451.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961. Vol. 1, pp. 83-90, no. 25; vol. 3, pp. 124-130.

Ertuğ, Ahmet. The Seljuks: A Journey through Anatolian Architecture, 1991, p. 78.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 524.

Gülyaz, Murat Ertuğrul. "The Kervansarays of Cappadocia", Skylife Magazine, December, 1999.

Hamilton, W. Researches in Asia Minor, 1842.

Hillenbrand, R. Islamic Architecture: Form, function and meaning, 1994, fig. 6.39, p. 552.

Ibni Bibi. El Evamirü'l-Ala'iye, Fi'l-Umuri'l-Alai'iye (Selçuk Name), trans. Mürsel Öztürk, 1996, p. II, 124.

Karpuz, Haşim & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, vol. 1, pp. 70-74.

Konyalı İ. H. Abideler ve Kitabeleri ile Niğde Aksaray Tarihi, Istanbul, 1974, p. 1124, 1137.

Kuban, D. Selçuklu Cağinda Anadolu Sanati, 2002, pp. 242-243.

Marquez Bueno, Samuel, & Gurriarán Daza, Pedro, & Martínez Núñez, María Antonia. (2024). Puertas de Corona (Taç Kapi) silŷūqíes: un camino de ida y vuelta entre Konya y Sultanhanı (Turquía), a la luz de la arqueología de la arquitectura y de la epigrafía. Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 31, 2024.

Moltke, H. Briefe über Zustände und Begebenheiten in der Türkei aus den Jahren 1835 bis 1839. Berlin, 1841.

Oberhummer, R. & Zimmerer, H. Durch Syrien und Kleinasien, 1898.

Özergin, M. Kemal. Anadoluda Selçuklu Kervansarayları, Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 162, n. 115.

Sarre, F. Reise in Kleinasien. Sommer 1895. Forschungen zur Seldjukischen Kunst und Geographie des Landes. Berlin: Georgraphische Verlagshandlung, 1896, p. 78, 94.

Sterrett, J. The Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor during the Summer of 1885. Boston, 1888, p. 16.

Tschihatscheff, P.A. Reisen in Kleinasien und Armenien, 1867, p. 8.

Unsal, Behçet. Turkish Islamic architecture in Seljuk and Ottoman Times, 1071-1923. London, 1959, p. 49.

|

|

|

main portal |

stalactite arch of main portal |

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p.71 |

side arcade of main portal |

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p.70

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p.71

|

|

detail of polygon interlace panel on entry portal |

courtyard kiosk mosque, stairs on south side |

|

kiosk mosque, view from entry |

kiosk mosque, detail of decorative stonework |

|

western arcades |

western arcades |

|

western arcades, southern end |

detail, decorative arch borders in courtyard |

|

east side courtyard cells |

wall consoles in refectory |

|

photo taken in 1884 by J. H. Haynes during the Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor (Photographs of Asia Minor, #4776. Division of Rare Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library) |

covered section, view to side aisles |

|

covered section, view of central dome |

covered section, exterior view of cupola and drum |

|

external view, eastern side |

|

|

Hittite Monument with hieroglyphics found at the Sultan Han in 1928 Ankara, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

|

Turkish stamp set from 1982 depicting the Sultanhan Aksaray

|

|

photo taken in 1884 by J. H. Haynes during the Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor (Photographs of Asia Minor, #4776. Division of Rare Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library)

|

Sketch of the han by Ainsworth in 1835

|

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 443; photo I. Dıvarci

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p.72 |

|

photograph taken by Sarre, 1895

|

The crown door of the Sultan Han drawn by Sarre, 1895 |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 438

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 443; photo I. Dıvarci

|

|

The inner covered section photographed by Gertrude Bell in July, 1907 (photo I-207)

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 447; photo I. Dıvarci |

|

photo taken in 1884 by J. H. Haynes during the Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor (Photographs of Asia Minor, #4776. Division of Rare Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library) |

photo taken in 1884 by J. H. Haynes during the Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor (Photographs of Asia Minor, #4776. Division of Rare Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library) |

|

The main portal photographed by Gertrude Bell in July, 1907 (Photo I-196) |

Photo by Erdmann (#133)

|

|

Photo by Erdmann (#120) |

Photo by Erdmann (#121) |

|

Photo by Erdmann (#122) |

Photo by Erdmann (#123) |

|

Photo by Erdmann (#125) |

Photo by Erdmann (#126) |

|

Photo by Erdmann (#127) |

Photo by Erdmann (#128) |

|

Photo by Erdmann (#129) |

Photo by Erdmann (#131) |

|

Photo by Erdmann (#134) |

Photo by Erdmann (#135) |

|

Photo by Erdmann (#136) |

Photo by Erdmann (#137) |

|

Photo by Erdmann (#119) |

|

|

western side view |

|

The Sultan Han Aksaray in 2007 |

|

The han as viewed by Gertrude Bell in July, 1907, one hundred years before the photo above (photo I-195b) |

|

undated photograph, late 19th c. |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 434; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 451; photo I. Dıvarci |

The Aksaray Sultan Han has a starring role in the widely popular Turkish television series Diriliş Ertuğrul. This rip-roaring saga relates the origins of the Kayi tribe (oba) of Turkmen who later became the Ottomans. The villainous Karatoygar, one of the emirs of the Seljuk Sultan Alaeddin Keykubad, is an ambitious double-agent of sorts, playing whatever side suits him best. He is in cahoots with the Knights Templar, holds Seljuk nobility (including the lovely Halime, the love interest of Ertuğrul) for ransom, all the while providing arms to Ertuğrul's uncle Kurdoğlu, who wants usurp Ertuğrul's father to take the leadership of the oba. The headquarters of this villain is none other that the Aksaray Sultan Han, named the Karatoygar Han in the series. The very first episode, dated 1225, shows a computer-generated reworking of the han. The han was built 5 years later than this date, but let us indulge a bit of poetic license for the sake of establishing the Seljuk setting.

|

|

for a series of photos taken of the han in 1963 by John Ingham, showing the condition of the han prior to its restoration, click below:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

©2001-2025, Katharine Branning; All Rights Reserved. No part of this site may be reproduced in any form without written consent from the author.