AK HAN

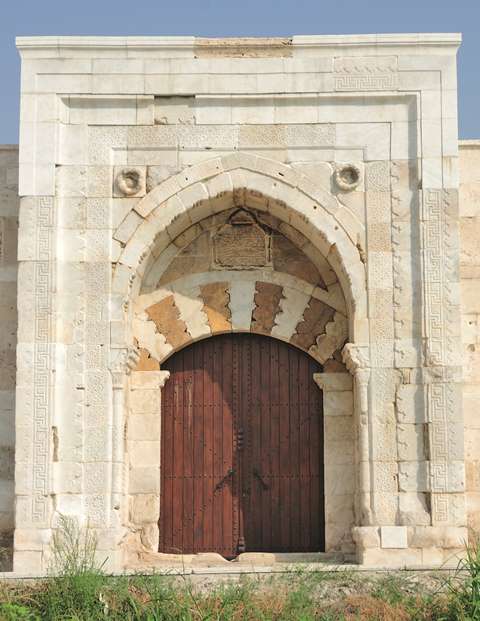

The Ak Han has a highly-original design concept for its portal, covered with a veritable zoo of animals. Two impressive hawks on the portal greet your arrival to this, the westernmost han of the Seljuks. It bears not one, but two, dated inscriptions and was built by a well-connected political figure of the day.

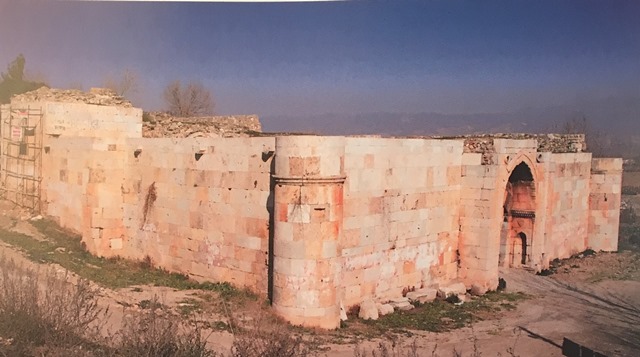

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 205; photo I. Dıvarcı |

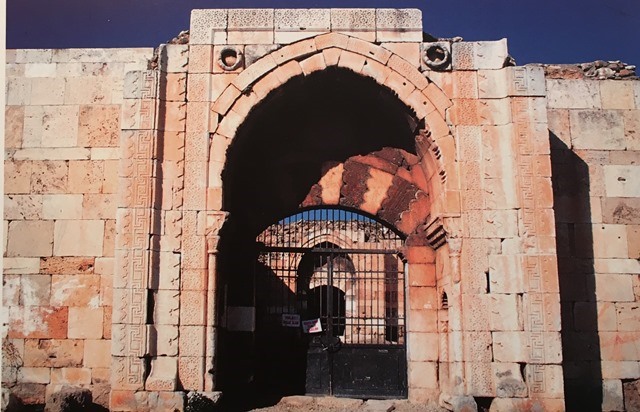

Eravşar, 2017. p. 209; photo I. Dıvarcı |

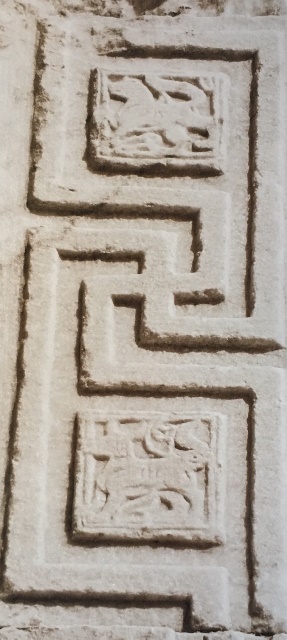

Eravşar, 2017. p. 217; photo I. Dıvarcı |

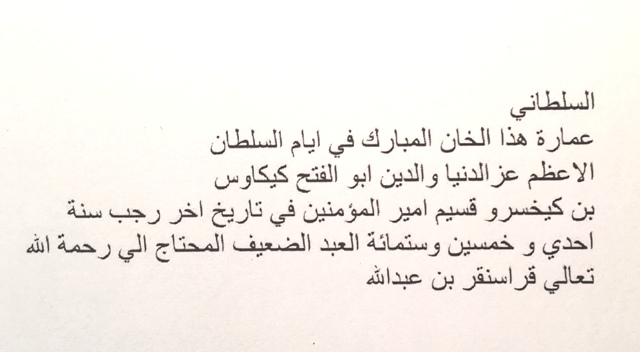

inscription over the covered section door |

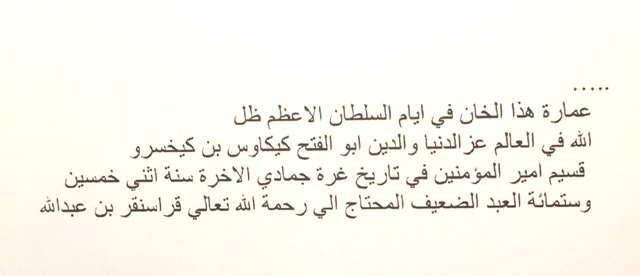

inscription over the main door leading into the courtyard |

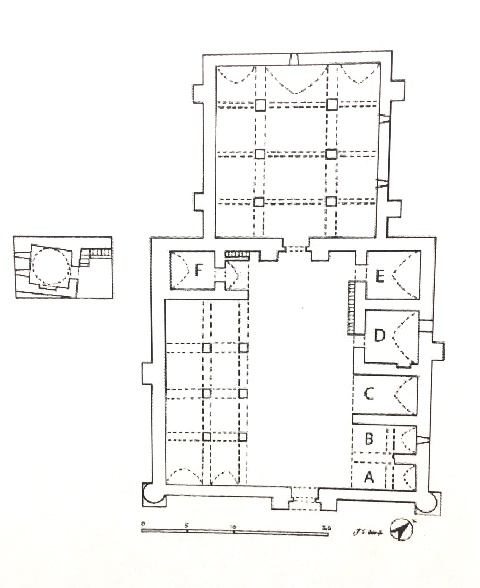

plan drawn by Erdmann |

plan drawn during the 2007 restoration |

photo courtesy of Ahmet Kuş |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 211; photo A. Kus |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 216; photo I. Dıvarcı |

| the photos below show the han before the renovation of 2006-2007: |

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p. 238 |

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p. 238 |

Photo by John Ingham (1963) |

Photo by John Ingham (1963) |

Photo by John Ingham (1963) |

Photo by John Ingham (1963) |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

Bilici, vol. 1 p. 348 |

Bilici, vol. 1 p. 353 |

Bilici, vol. 1 p. 353 |

DISTRICT

20 DENIZLI

LOCATION

37.818071, 29.135407

The Ak Han is located in the Mederes Valley, on the Denizli-Dinar-Afyon road, 7 km northeast of Denizli, near the village of Goncalı. It is situated near a single-arched bridge which passes over the Çuruksu (Gökpinar Emirsultan) River on the Denizli-Afyon Road (route 330) to the south of the han. This river was known in Antiquity as the Lycos River. This bridge was most probably built in the Seljuk period.

Denizli was the last town at the western edge of the Seljuk Empire. This was an important checkpoint that controlled the junction between western and central Anatolia. A modern highway passes near the han. Erdmann stated when he visited the han that the ancient caravan road ran parallel to the modern highway. The road passing by the han, an old trail used in the Byzantine period, went from Konya and Beyşehir to Laodicea and Eğirdir. This road, which connected the Aegean region with central Anatolia, had been heavily-used throughout history. Nearby are the ruins of Laodicea (ancient Denizli) and springs of Pamukkale.

OTHER NAMES

Goncali Han

Bozhan

One of the oldest records relative to the han dates from the period of Suleyman the Magnificent. His troops, on route to the Rhodes campaign, stopped by this han when they passed through Denizli. This road was heavily traveled throughout history. Pococke, traveling on this road in the mid-18th century, described the han as being located next to a bridge and built of white marble brought from the nearby ancient city and reported seeing sculptures of two dragons and a Medusa head on its walls. A number of Western travelers have mentioned this han, using variants of the name of Ak Han. These include Arundell (1826), Hamilton, (1842) Davis (1874) and Sarre (1895), who published its plan and a photograph of the façade.

The name of the Ak (White) Han could have been derived from the white marble used in its construction. However, it is more likely that the name was associated with the nearby Ak Su stream. Some travelers called it the Boz Han, in reference to its gray color.

DATE

1253/4

Dated by two inscriptions: one of 6 lines in the covered section and one of 5 lines in the

courtyard.

REIGN OF

Izzeddin

Keykavus II

INSCRIPTION

Both the crown door of the courtyard and the door of the covered section have an inscription in Arabic. The inscriptions are eroded and thus not easily legible. The dates are therefore not clear. However, Erdmanns reading of the dates is accepted as correct. Both inscriptions indicate the name of the patron as Şeyfettin Karasungur.

The Arabic inscription of five lines on the entrance door of the covered section reads as follows:

"The construction date of this Han is at the end of the month Rajab, 651 H. [25 September 1253]. Built during the time of great Sultan Abu'l-Fath Keykavus [Izzeddin Keykavus II, r. 1246-62], son of Keyhüsrev and servant of believers. Built by Karasunkur bin Abdullah, the poor servant in need of the mercy of Almighty God.

A second inscription in Arabic, with four lines, is located above the crown door of the courtyard. The inscription is flanked with two small columns decorated with rosettes on their capitals. However, the first line of the inscription has been erased and the date is not legible, although it is believed to read 1254.

The inscription over the courtyard door reads as follows:

.This han was built earlier in the sixth month of the year six hundred and fifty-two [1 Jumada II 652, or 19 July 1254], during the time of great Sultan Abu'l-Fath Keykavus, son of great sultan Keyhüsrev, the partner of the head of the believers, the shadow of God on Earth and by the hand of His weak slave, Abdullah bin Karasungur, in need of the mercy of the supreme God.

The difference in the dates (1253 and 1254) probably indicates the dates of the beginning and end of the construction, and suggests that the covered section was built in 1253 before the courtyard which was finished in 1254, which is generally the case for Seljuk hans.

PATRON

The inscriptions indicate that the han was dedicated to the Seljuk Sultan Izzeddin Keykavus II and that it was built as a charitable institution funded by Governor Şeyfettin Karasungur ibn Abdullah, Emir of Ladik and brother of the famed Seljuk vizier Karatay.

The patron of this han had a colorful life. Karasungur was a son of Manuel Maurozomes, a Byzantine Greek courtier who served the Seljuk sultanate, and the brother-in-law of Sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev I. Karasungur became the governor of Ladik, the center of the Seljuk west, for over 20 years. His brother was Celaleddin Karatay, who became the highest official in the Seljuk state, serving under three Sultans. He is mentioned in the foundation documents of his brother Karatay as the Buyuk Emir (Great vizier). His other brother, Kemaleddin Rumtaş, also held important roles in the government.

He was the proverbial right man at the right moment in a critical time of transition for the Seljuks. The Mongol invasion of Anatolia in 1243 and the defeat at the Battle of Kösedağ brought major changes to the Seljuk state. The Seljuks were forced to accept to pay a tribute to the Mongols, and it was during this new political atmosphere that the Akhan was built in 1253-1254.

Karasungur and his family were well-established in the Denizli region. Back in 1197, Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev I lost the throne to his brother, Rükneddin Suleymanşah (r. 1196-1204) of Tokat. While in exile in Byzantine lands, Rükneddin died and Giyaseddin appealed to the Byzantines to retake the throne. He captured Ladik and gave its control to Karasungurs father-in-law, Manuel Maurozomes, a member of the family of Comnenus. This region became a buffer state between the Seljuks and the Byzantines, and then was totally annexed by the Seljuks in 1206. Denizli (Ladik) became the provincial capital of the Seljuk west. After the Seljuk conquest, Byzantine Laodicea became Seljuk Ladik (Denizli), the center of the Seljuk west. Seljuk institutions were built in the region, such as the Ulu Camii of Denizli and the caravanserais of Cardak (1230), Haci Eyuplu (1235) and Ak Han (1253). This was an active trading area and a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural region: Greeks, Turks, Crusaders, Arabs, Jews, Saracens, Venetians, Georgians, Pechenegs, Mongols, Slavs, Kipchaqs, and Armenians all lived and traded here.

Not only was Seyfeddin Karasungur ibn Abdullah in the thick of the political elite, but he was also an active builder. He was one of six Seljuk governors who commissioned more than one building project. His name appears on the reconstruction inscription of the walls of Antalya in 1225, where he served as provincial governor in 1225-26. He then became the governor of Ladik (Denizli) during the reigns of Alaeddin Keykubad I and Izzeddin Keyhüsrev II. He is the builder of the earliest monuments in Ladik (Denizli), where he commissioned nine buildings in total. In addition to the Ak Han, another han was built by Seyfeddin Karasungur in 1235. It was called the Haci Eyüplü Han, but no traces of it exist today and its exact location is not known. Its foundation inscription, discovered in 1931, is now kept in the Pamukkale Museum. The nine Denizli projects of Karasunger include: the Denizli Kalesi (Kaleiçi), the Haci Eyüplü Han, the Ulu Camii (1247), the Yenihan (Vaikfhani) and the Ak Han. His name appears on the fountain inscriptions found in the regulation works around the Grand Mosque in Denizli (1247), and on the inscription of the Yeni (Karasungur) Han in the center of Denizli (1249-50).

After 1254, there is no evidence of further building activity on his part. The Seljuk vizier Pervane Suleiman of Tokat sent him to Damascus in 1268. He was one of the Seljuk high officials captured and freed by the Mamluk ruler Baybars near Elbistan in 1276. There is no further information about his later years.

BUILDING TYPE

Covered

open courtyard (COC)

Covered section smaller than the courtyard

Covered section with a central aisle perpendicular to the rear wall and 1 aisle

on each side

4 bays of vaults

DESCRIPTION

The han is oriented on an east-west axis. It consists of a closed section used for lodging and a courtyard with service areas. The crown doors of the covered and courtyard sections are on the same axis. The covered section is smaller in scale than the courtyard. The entrance door faces east and the road passes in front of the door. The ground level of the covered section is higher than the courtyard.

Main entry portal: The main portal is more highly-decorated than the portal of the covered section. The crown door of the han leading into the courtyard is slightly offset the center of the east facade and projects from the main wall. It projects from the facade and is taller than it. The composition of the crown door consists of a pointed arch, supported by a thinner arch above. The tympanum of the crown door is surrounded by an arch located immediately below the arch forming the door opening. The inscription plaque, located in the middle of the tympanum, has the form of a three-lobed arch carried by two columns. The flattened arch of the door opening is made of interlocking tongue and groove stones in two different colors. The support stones of the arch are based on consoles at the sides. Segmented oval recesses are seen on the inner surface of each stone of the arch of the crown door. Remains of rosettes can be seen on the arch corners, although most are broken off today.

The courtyard portal is elaborately decorated with a series of four borders comprised of different decorative elements. The first border has eight-pointed stars intersecting each other. The second border from the outside is composed of square panels set among the arms of swastikas with small squares between them, each inlaid with different animal figures surrounded by geometric and floral motifs. Some of the animals seen in this border include animals such as deer, mountain goats, eagles, lions, hawks, dragons with tails, wolves and bulls. There are also several unidentified animals as well as two human portraits. The third border is comprised of six-pointed stars and the fourth has intersecting octagons with rosettes in their centers.

Small columns in the corners of the crown door opening connect the inner surface to the outer sections. A band of vegetal decoration separates the column shaft from the capital, which is decorated with a figure of a hawk seen in profile, with the two hawks facing each other. These hawks are particularly impressive. As the donor of the Ak Han is the statesman Karasungur whose name means Black Falcon, these birds might be a reference to his name.

There is a niche on each side of the inner surface of the crown door, which end in the form of a half shell. Columns with capitals are located on each side of the niches. The capitals consist of two parts; above is an octagonal panel inside a square frame with a central rosette, and below is a half-decagon decorated with half rosettes. Floral motifs are seen inside of pendants on the top of the niches. Above, there are three rows of muqarnas.

Courtyard: The courtyard is square in plan, and is located to the east of the covered section and is slightly larger than it. The entrance is in the same axis as the entrance to the covered section. The crown door does not include any rooms behind it and opens directly onto the courtyard. The courtyard floor is laid with stones, and slopes slightly from west to east, both of which facilitated the drainage of rainwater. The courtyard is surrounded by extensive service facilities including a bath and mosque, which contrasts with the more modest covered section.

The right side (northern) of the courtyard is divided into two parts with an iwan in the middle. The iwan is covered with a pointed vault in the direction of the courtyard. The iwan is approximately the same height as the courtyard floor, and is surrounded by a support arch including a vaulted arch. Both the arch and the supports of the vaulted arch stand on the consoles with lion heads facing the inner side of the iwan.

The two rooms on the right (north) side closest to the entrance served as the bath. They are two-storied, but most of the walls and roofs have collapsed, so it is not certain how the upper floors were reached, but a system of console stairs along the wall was probably in place (as is seen in the rooms on the other side of the iwan). The first room, covered with a north-south vault, was the dressing room and tepedarium. Also found here is an elongated space which served as a latrine. The second room was the water reservoir and contained a small window and traces of the brick water tank and water pipes in the wall. These pipes appear to be a part of the water supply and drainage system. The water pipes may have also fed a fountain similar to the one seen in the Karatay Han. Another floor, located underground, was visible before the restoration. The narrow section would have been used for the water tank for the bath and the arched space below would have been the entrance to the furnace room. The room in front of the water tank would have been the caldarium (hot room) of the bath.

To the west of the iwan are two square rooms entered through the courtyard and which are covered with pointed vaults. The room to the west includes reuse spolia material with carved rosettes at the corners of the entry arch. Inside the room to the west of the iwan is an arched niche and a door opening on the northern wall. Console stair steps, most of which are currently broken, rise from west to east on the wall surface between the doors. The original function of these two spaces is not certain.

The left side of the courtyard (southern section) comprises an open arcade, but it has collapsed. During the restoration project carried out in the 1970s by the General Foundations Directorate (Vakiflar Genel Müdürlügü) this arcade was approximately restored. This arcade of two naves is formed by two support lines, each based on three piers extending in the east-west direction. The piers are connected to each another by support arches which extend in the north-south direction.

Mosque: A separate room is located at the far left-hand (southwest) side of the courtyard. It has two floors and the second floor is believed to have served as the mosque. A staircase of cantilevered steps, set on two piers, leads up to the door opening. The prayer room is covered by a dome on the interior and a pyramidal dome on an octagonal drum with chamfered corners on the outside. The original mihrab was dismantled and is filled in with masonry today, but its remnants can be seen at the section near the base. This room is entered through a low-arched door, opening onto an antechamber in the form of an iwan and adjacent to the crown door of this covered space.

The threshold of the door is six steps higher than the inner section and the courtyard floor. The flat lintel and jamb of the mosque door were built with reuse spolia material and a rosette is placed on both corners of the flattened arch. The difference in the elevations has led some scholars to posit that a Byzantine structure existed there prior to the construction of the han. Old photographs of the mosque reveal that the wall of the mosque was distinctly separate from the wall of the covered and service sections, so it does seem possible that it could have existed before the construction of the courtyard service areas.

During the renovation, the remains of an exterior bath were found as well, but it is believed to be a later addition.

Covered section: The covered section of the han has three naves extending perpendicular to the wall opposite the entrance. The central nave is wider and higher than the side aisles. Its vault is made using pitch-faced stones and the support arches are made of smooth-faced stones. The naves are divided into three sections by two horizontal support lines, each based on three piers (6 in total) and connected to one other with four pointed arches. The naves are covered with pointed vaults. The middle nave extending in the east-west direction is higher than the other naves. This vault is also reinforced by ribbed arches extending in the north-south direction. Smooth profiles are seen on the piers of the central nave at the connecting point with the ribbed arches.

Lighting is provided by three slit windows; two in the eastern wall and one on the northern wall. The opening which served for lighting and ventilation in the middle of the covered section is not visible and was probably filled in at a later date.

The loading platform in the middle nave was discovered during the recent renovation of the han. They were built about 40 cm above the ground and steps leading to the platform are located opposite the entrance to the nave. It would appear that both sides of the platform were arranged to serve as a stable area, but no traces of the original feed troughs were found.

The crown door of the covered section faces east and is located in the middle of the eastern bearing wall and projects from it. This is a remarkable crown door, executed with great craftsmanship.

Two spolia blocks symmetrically flank the portal and have meander elements with squares between them. The squares are decorated with floral (palmettes and split-leaf rumi elements) and geometric ornamentation. The spolia block on the left has three rosettes and a Seal of Solomon (six-pointed star) element. The spolia stone on the right has similar design with a pinwheel in addition. The crown door is composed of a pointed arch surmounted by another thin arch placed to help distribute the load. Two engraved reliefs, eroded today, can be seen in old photographs at the corners of the crown door and a single rosette, missing today, was set on the keystone. The inscription, located in the middle of the tympanum, is set inside a pointed-arched panel comprised of a slab of marble in two sections, framed with flat, rectangular stones. The low-arched door opening underneath the inscription panel is inset from the arch above it and is formed by interlocked stones of two different colors.

The outer walls of the covered section are supported by two polygonal buttresses on the northern and southern walls, but there is no buttress on the western wall because it is built against sloping land.

EXTERIOR

The northern and southern walls of the service areas are reinforced by two rectangular support towers at the front corners and include two circular cross-sectioned support towers built on square bases.

At the end of the wall of the main portal is a cylindrical buttress built of smooth-cut stone. The side walls of the courtyard are supported by polygonal buttresses.

BUILDING MATERIALS

Smooth-cut white stones were used in the façade, the mosque and for the western side of the courtyard. Numerous reuse spolia blocks, used in every section of the han, were most probably taken from the ancient site Laodicea, only 1 km away. It is estimated that 50% of the stones blocks used in this han are spolia.

Lesser-quality porous stone blocks were used on the covered section, giving it a brown color, whereas the stones used in the courtyard are white in color. The walls are built with the rubble wall technique, which consists of filling two rows of smooth stones with a mixture of mortar and rubble. Pitch-faced stones were preferred for some parts of the vaults. Elaborate stonework is seen at the entrance facade of the courtyard. Two walls of fine masonry rise above three rows of thick masonry, which indicated that several different masons worked on the project. Bricks were used on the inner face of the niche of the mosque and the spaces of the inner bath.

The covered section was built first, as indicated by the inscription. The construction phases of the covered and courtyard sections are close in time, as indicated by the two inscriptions. It is clear that the service areas were planned from the onset as an integral part of the han.

DECORATION

This has has come to be known as the "White Han" due to the beautiful white stone used on the front entry door and in the mosque. The main portal is magnificent with its geometric relief decorations and its sparkling white brilliance.

The portal of this han can compete in refinement with that of the Karatay Han. The Ak Han offers a veritable zoo of animals on its portals for our viewing delight. All in all, there are 16 animal figures (dragon, lion, rabbit, bull, eagle, griffon, dog, winged lion or tiger, bird, antelope; all in apparent movement). This han differs from other hans in its choice of this figurative ornamentation seen between the arms of the swastikas. Many decorative features placed on these crown doors are not seen on other hans of the Seljuk period. Most portals favor geometric and floral designs, and, as such, this portal with its zoo of animals is unique. It is interesting to note that a large role was given to animal figures as well at the Karatay Han, commissioned by Karasungurs brother Karatay.

The entrance door to the courtyard section not only is rich in animals, but also with geometric designs which bear a relationship to the zodiac. Rosettes are set in the center of eight-pointed stars, which clearly shows the close relationship of the architectural decoration of the Seljuk period with astronomy. Each of the rosettes set in the center of the geometric patterns represents a planet. The swastika motifs on crown doors are also seen in other hans of the Seljuk period, such as in the Ağzıkara and Zazadin Hans.

There are also two human figures on each side of the main portal. They are wearing a tunic, and have life-like features with big eyes, eyebrows and a mouth. They face frontally.

The two lion-head shaped springers at the iwan of the Ak Han are carved in white stone, a nice decorative touch which serves to make them stand out against the other stones of the portal.

DIMENSIONS

The total area of the han is 1100m2

Covered section area: 270m2

Courtyard area: 625m2

STATE OF

CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

The Ak Han was first restored in 1970, at which time the arcade on the southern side of the courtyard was rebuilt. After the restoration, the han was used as an open-air museum. Excavations were then carried out between 2006 and 2008 by the Denizli Museum, at which time the spaces of the courtyard were unearthed and their plans became clear. The Ak Han is now used as a restaurant and a local wedding reception hall, a popular readaptive use for hans.

Alas, this renovation has not been a total success. Functional elements for the restaurant, placed within the building, have overshadowed the original appearance of the structure. The most unfortunate restoration error was carried out on the crown door, where decorative elements hundreds of years old were cleaned with overly-abrasive methods, resulting in blurred edges to the decorative motifs. In addition, some of the decorative elements of the crown door of the courtyard were displaced to other areas around the han, disrespectful of their original locations. Let us hope that the joy of new bridal couples married in this historic site will help to parry these restoration misfortunes.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı Publications, 2007, p. 452.

Altun, Ara. An Outline of Turkish Architecture in the Middle Ages, 1990, p. 200.

Arundell, F. V. J. Discoveries in Asia Minor, including a Description of the Ruins of Several Ancient Cities. London: 1834, v. II, p. 162.

Bayhan, Ahmet Ali. Ak (Goncali) Hanı, Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara Kültür Bakanlığı, 2007, pp. 286-303 (includes bibliography).

Bayrak, M. O. Türkiye Tarihi yerler kılavuzu, 1994, p. 175.

Bektaş, Cengiz. Selçuklu kervansarayları, korunmaları ve kullanılmaları uzerine bir öneri = A proposal regarding the Seljuk caravanserais, their protection and use, 1999, pp. 146-148.

Beyazit M. Seyfeddin Kara Sungur: Anadolu Selçuklu Ucunda bir Vali ve Imar Faaliyetleri. In Uluslararasi Denizli ve Çevresi Tarih ve Kültür Semposzumu. Isparta, 2007, pp. 151-158.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 1, pp. 348-353.

Davis, E. J. Anatolica: or, the Journal of a Visit to some of the Ancient Ruined Cities of Caria, Phrygia, Lycia and Pisidia. London, 1874, p. 114.

Demir, Ataman. "Anadolu Selçuklu Hanları. Akhan 'Denizli' ", İlgi, 57 (1989), pp. 9-13.

Durukan, Aynur. Ak Hanın Süsleme Programı, Güner İnala Armağan, Ankara, 1993, pp. 143-160.

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 205-217.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961, pp. 67-69, no. 19; vol. 3, pp. 161-162.

Eyice, Semavi. Akhan in Türkiye Diyanet Vakfi Islam Ansiklopedisi. Istanbul, 1989, p. 236.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 477.

Hamilton, W. Researches in Asia Minor, 1842, v. I, p. 522.

Karpuz, Haşim & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, vol. 1, pp. 238-239.

Kutlu, Mehmet. Seljuk Caravanserais in the Vicinity of Denizli: Han-Abad (Çardak Han) and Akhan [masters thesis]. Ankara: Bilkent University, 2009.

Özergin, M. Kemal. Anadoluda Selçuklu Kervansarayları, Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 144, n. 4.

Pococke, R. A Description of the East, and some other Countries (vol. 1-2). London, 1745, p. 78.

Rice, Tamara Talbot. The Seljuks in Asia Minor, 1961, p. 205.

Roux, J.P. Le décor animé du caravansérail de Karatay en Anatolie. Syria 49 (3), 1972, pp. 395-96.

Sarre, F. Reise in Kleinasien. Sommer 1895. Forschungen zur Seldjukischen Kunst und Geographie des Landes. Berlin: Georgraphische Verlagshandlung, 1896, pp. 10-13 ; 84.

Taeschner, F. Osmanli Kaynaklarina gore Anadolu Yollari, 1924. Translated by TKK Kütüphanesi Basilmamiş Tercümeler, no, 131, 2010, p. 172.

Turan, O. Selçuklular Zamaninda Türkiye, 1996, p. 518.

Uzuncarsili, I. Hakki. Afyon Karahisar, Sandikli, Bolvadin, Çay, Işakli, Manisa Birgi, Muğla, Milas, Peçin, Denizli, Isparta, Atabey ve Eğirdirdeki Kitabeler ve Sahip, Saruhan, Aydin, Menteşe, Inanç, Hamit Oğullari Hakkinda Malumat. Istanbul, 1929: vol 1, pp. 195-196.

Yaltkaya, M.Ş. Baypars Tarihi. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 2000, p 86, 157.

Yavuz, A. T. Akhan in Ululararasi Denizli ve Çevresi Tarih ve Kültür Sempozyumu Birdililer. Isparta, 2007, pp. 133-140.

|

Main entrance

|

View into courtyard from main entry

|

Chevron decor on main portal

|

Steps in courtyard leading to upper storey mosque

|

Iwan in courtyard

|

Arcades in covered section

|

Erdmann was quite taken by the beauty of this han, which is reflected in the series of photos he took of it:

|

Facade Photo by Erdmann (#84) |

|

|

left side view of exterior: Photo by Erdmann (#83) |

left side of entry showing mosque on upper level Photo by Erdmann (#86) |

|

entry crown door Photo by Erdmann (#94) |

Crown portal of covered section Photo by Erdmann (#87) |

|

niche on left side of main entry portal Photo by Erdmann (#95) |

fretwork on left side of main entry portal Photo by Erdmann (#96) |

|

fretwork detail on main door Photo by Erdmann (#97) |

Entry door to mosque on left side of entry Photo by Erdmann (#89)

|

©2001-2025, Katharine Branning; All Rights Reserved.