KARATAY HAN

The Karatay Han is a dazzling han with fixtures fit for a sultan. The existence of a tomb in this han makes the Karatay Han a unique example among Anatolian hans. It is important as its rare foundation deed provides valuable information about daily life in a han. It also includes one of the rare depictions of an elephant in Seljuk art.

|

|

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 394; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 403; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

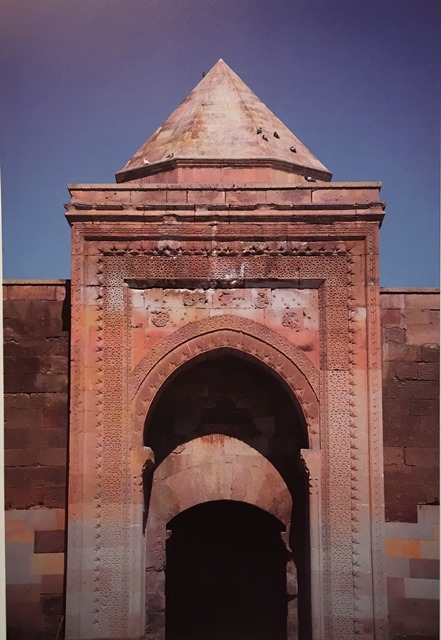

main portal with buttresses |

|

Inscription plaque (kitabesi) over main entry portal |

|

inscription plaque on courtyard portal |

Buttress tower with distinctive rope design |

Detail of lace arabesque carving of main portal and humanoid drain spout |

|

Water spout of human figure (head now missing) |

|

Entry left: fountain/hamam area, surmounted by the famous animal frieze |

|

The famous frieze of 17 niches of animals in the entry vestibule |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 400; photo I. Dıvarcı |

detail of elephant figure from entry |

Tomb chamber ceiling with groin vault decorated with turquoise ceramic tiles |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 399; photo I. Dıvarcı |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 409; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p. 476 |

|

inscription plaque over covered section door The photographs of inscription plaques were taken by Prof. Dr. Zafer Bayburtoğlu; transcription by Halit Erketlioğlu (Kayseri Kitabeleri, 2001, pp. 62-63.) |

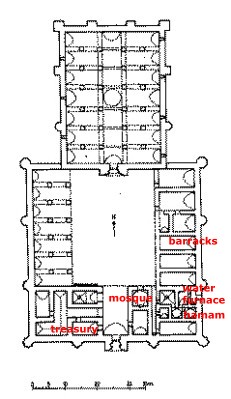

plan drawn by Erdmann |

|

Courtyard arcade of cells, western side |

|

Central aisle of covered section |

View looking from courtyard to main entrance; steps leading to roof terrace |

Portal of the covered section |

Snake head knot detail over above courtyard door |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

Buttress towers of external walls |

|

|

Stone carving showing an elephant and a leopard; Konya Ince Minare Museum |

DISTRICT

38 KAYSERI

LOCATION

38.644219, 35.935152

The Karatay Han is located 50 km east of Kayseri on the Pinarbasi-Malatya

Highway past Elbaşi in the village of Karadayi. The han

is located on the road that was the former trade route that linked Kayseri with

Malatya and the south. No traces of the old caravan route remain; however, the

modern Kayseri-Malatya highway, which passes in front of the han, follows this

route. A characteristic of this han is its proximity to the

Yabunlu Bazaar, which was an important international trade fair in the 13th

century.

The Karatay Han was built on the old Kayseri-Malatya road, part of the main trade route into Syria. The areas of the towns and villages surrounding the hans turned into small commercial centers. The Karatay Han in the 13th century stood at a junction of roads leading from Syria, Iraq, eastern Anatolia and Iran to Kayseri and Sivas. It is hard to imagine that the quiet rural village of today was once a teeming trade center.

OTHER NAMES

The han is named after its patron, the vizier Celaleddin Karatay.

The charter of the Karatay Foundation, the oldest record concerning the han, states that the han was built by Vizier Celaleddin Karatay, yet it makes no specific mention of the name of the building itself, and it has been suggested that the name of Karatay was added at a later period in honor of the vizier.

The Karatay Han is important, not only for its impressive size and decorative excellence, but for the fact that it provides documented information concerning the life of the han. The vakif foundation document is detailed, and, furthermore, the journals of Qadi Muhyiddin Ibn Abduzzahir, who traveled with Baibars during his campaign in 1277, furnishes a beautiful description of the han.

Indeed, the size and wealth of the han was not lost on medieval travelers. A significant reference to this han is found in the journal of Qadi Muhyiddin Ibn Abduzzahir. In his role as the historian who accompanied the Mamluk Sultan Baybars on his campaign to Anatolia, Qadi Muhyiddin Ibn Abduzzahir recorded the events of the trip in a diary and included a detailed description of this han, where Baybars stayed overnight during his 1277 campaign in Anatolia against the Mongols. The following lines illustrate how impressed he was by the splendor and beauty of the Karatay Han:

"Before long, we arrived at the caravanserai called the Kara Tay Han, a caravanserai that showed the merit of its master, who built it to attain the reward of the Creator. This building is one of the most magnificent works for its width and height; and its shape and appearance are most beautiful. Red stones, dressed and polished like marble, were used for the construction of this structure. Its walls and columns are embellished with carved tracery so fine that even a pen could not achieve such delicacy. Outside are markets with two doors and fortified walls, and the ground is paved with flagstones. The doors are made of the very best iron and built in the most striking way. The interior of the caravanserai consists of iwans and stables which can be used for shelter in both summer and winter. In short, it is difficult to convey the true magnificence of this place. The han contains all that is needed to refresh the traveler in summer and winter. Passengers can find here whatever they need, come summer and winter. In addition, bathing facilities, a hospital, medicines, bedding and utensils are provided in the caravanserai. Every passenger, no matter his origin, is served a meal according to his budget. Our Majesty the Sultan [the Mamluk Baybars] was offered a banquet worthy of him when he came here. Although many people gathered round to see him, none could approach his table. This caravanserai is funded by a very rich foundation, supported by revenue coming from the many villages surrounding it and from other cities nearby. Moreover, the caravanserai has a governing committee with a manager, scribes and clerks to attend to the income and expenses. The Tatars [Mongols] did not interfere with the management and revenue of the caravanserai because of its good service to the Anatolian people, and which glorified the owner with Gods mercy.

A han this large did not go unnoticed. References to it are found in Seljuk historical sources, notably in Ibni Bibi, who provided detailed information about the size and imposing appearance of the Karatay Han. The Italian Balduci Pegolotti, in this region around 1353 and who prepared a guide for traders, called the caravanserai the Gavazera del Amiraglio (The Caravanserai of the Admiral). Pegolotti stated that he was surprised that he did not find anything else as nice as this when he arrived in Kayseri. Other Western travelers who mentioned the han were Sterrett, Moltke and Naumann, who saw the han when he came to work on the construction of a railroad in Anatolia. He mentioned the tall towers of the han located in the center of the village, the inscription in Arabic on the door, and the diversity of its decoration. He has left us an engraving of the han.

DATE

1235-41 (dated by inscription)

Construction of this han started during the reign of Alaeddin Keykubad and was continued during that of his son, Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev, in 1240-1241.

However, it is not known when it was completed or when Karatay began his involvement with the construction process. Karatay took control during the period of weakened sultans that followed by Mongol victory at Kösedağ and most certainly took charge of finishing the construction of the han that was started by Alaeddin Keykubad and Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II. As only the names of the sultans are listed on the inscriptions, one is tempted to think that Karatay stepped in to complete the han after the death of Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev in 1246, a timeframe which corresponds to his other building projects. He gained considerable power during the reign of this weak sultan and must have accumulated an extensive fortune which found expression in the attention paid to the decorative elements of this han. The construction of this han can thus be situated between 1235 (first date on inscription and 1254 (date of death of Karatay).

INSCRIPTION

The han contains an inscription over both of the crown doors. Both inscriptions are carved in marble stone in Seljuk naskh calligraphy.

The four-line inscription on the entry to the covered section provides the name of Keykubad, son of Kaykavus, but no construction date is indicated. The inscription stone of the covered section door has blackened over time.

The inscription reads as follows:

"It is Allah the Eternal who owns all possessions. Keykubad, the son of Keyhüsrev, the most magnificent of sultans, head of all Khans, holder and governor of the umma, master of the sultans in the world, father of all conquests.

The inscription of five lines in thuluth script over the main crown door leading into the courtyard provides a precise date this time, 638 H (1240), along with the name of Keyhüsrev II, son of Alaeddin Keykubad I. The inscription reads as follows:

"This building belongs to God, who is One, Eternal, and Everlasting, August and Magnificent Sultan, King of Kings, the Shadow of God on Earth, Keyhüsrev son of Keykubad, Commander of the faithful in the year 638".

These two inscriptions give precise information that allows us to understand that there were two construction periods for the han:

- the large covered section was built under the reign of Alaeddin Keykubad I

(1219-1236) at the end of his reign. Work began during his reign but he only

lived to see the completion of the main covered section. The construction of the han was

probably interrupted for a few years after the death of the sultan until the

project was revived again by Karatay in 1240-41

- the open courtyard section was built in 638 (1240) during the reign of

Alaeddin Keykubad's son Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II. Under the patronage of

Karatay, the courtyard was added to the foundation and a mausoleum was built.

REIGN OF

Alaeddin Keykubad I for the

covered

section

Giyaseddin Kayhüsrev II for the courtyard

PATRON

The name of the patron of the han is not mentioned in either inscription, but the foundation charter of the han, one of the few that have survived, does indicate the name of Celaleddin Karatay as the patron who commissioned the construction of the han. The historian Aqsarayi mentions in his text that Karatay built a large and impressive caravanserai in the Zamantı region, referring to this very han.

All the force and intelligence of the personality of Karatay is translated in this han. One of the most powerful of all Seljuk statesmen, he was a devout Muslim and a charitable man of superior morals. He was a Byzantine Christian of Greek origin who converted to Islam. He served the Seljuk empire for over 40 years (1214-1254), under three separate sultans: Alaeddin Keykubad, Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II and finally during the triumvirate period of the sons of Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II. He certainly had as much, if not more, power than the sultans under whom he served. During the turbulent times of the Mongol invasions and the subsequent weakened sultanate, he the effective leader of government and held the Seljuk Empire together. The Seljuk vizier Emir Celaleddin Karatay also built a hospital in Antalya (1250; no longer existing) and the celebrated Karatay Medrese at Konya (1251), where he is buried. Karatay had two brothers, both of whom converted to Islam as well, adopted Turko-Islamic names and served as high-ranking officials of the Seljuk Sultanate. One of them Kamal al-Din Rumtash, built his own medrese (1248), now in ruins, directly across the street from that of his brother. The other brother, Karasungur, built the Ak Han near Denizli. Upon his death in 1254, legend states that the decline of the Seljuk Empire accelerated.

His piety took a mystic and acetic bent, and Sufis and all manner of religious men from far and wide sought him out. He was a friend of the other Celaleddin in town, the mystic Mevlana (Rumi). Bar Hebraeus leaves this portrait of Karatay in his journal: "And there was in Kanya (sic) a certain noble, an old slave of Sultan Ala ad-Din, whose name was Jalal al-Din Karatai (sic) and he was an ascetic who abstained from the eating of flesh, and from the drinking of wine, and from women, and he was a good and merciful man."

A curious case, however, is this patron Vizier Celaleddin Karatay. As a friend of Mevlana, a powerful vizier, an important patron of the arts, peacemaker and key liaison man with the Mongols, this man was certainly larger than life. One thing is certain: he was very smart and very ambitious, but he was also either very modest or very vain. Two incompatible episodes provide conflicting insight onto his character.

Karatay the Modest: Legend states that Celaleddin Karatay journeyed from Kayseri to see the finished han, and was so overwhelmed by its magnificence that he suddenly turned around and sped away again, afraid that he would be carried away by pride in his own accomplishment. The historian Aqsarayi relates the interesting episode as follows:

"When the caravanserai he built on the Elbistan road was completed, Karatay set off from Kayseri to see it, but when he came near Zemendu, he regretted his decision and turned back. Celaleddin felt that if he visited this magnificent building, he might become filled with a sense of pride, which would deprive him of deserving merit in the eyes of God. Out of fear of this trespass, he vowed never again to visit this caravanserai, which had no peer on earth. When the bookkeepers showed him the accounting ledgers and informed him how much money had been spent and the many outstanding bills, he ordered that they be burned, and commanded that the masters and workers be paid at once so as not to feel bothered by his debts unto them.

These two incidents related by Aqsarayi may be legends tinged by hagiography.

Emboldened by his power after the Mongol victory, Karatay stepped in and took over the construction of a han built by two previous sultans. While later 13th century sources confirm his identification with this han and his waqfiyya endowment deed has survived, it is interesting to note that neither of the two inscriptions for the han include his name, another argument militating for a modest character.

Karatay the Vain: what type of man would dare to show more importance than the Sultan under whom he served? Yet Karatay certainly did, going so far as to build this han which was considerably larger than the Incir Han built at the same time by Sultan Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II.

This type of arrogance was dangerous and could have been perceived as a breach of diplomacy which could have risked the ire of the Sultan (as Fouquet, Minister of Finances would learn a few centuries later, when the ostentation of his elaborate château, Vaux-Le-Vicomte, so angered King Louis XIV that he dismissed and imprisoned the Minister Fouquet). Cocky vizier or modest servant? You decide.

Lastly, Kadi Muhyiddin Ibni Abduzzahir mentions this caravanserai by name (Karatay Han) in his journal as one of the buildings the Mamluk Sultan Baybars visited in 1277 during his campaign into Anatolia against the Mongols.

BUILDING TYPE

Covered

section with open courtyard (COC)

Covered section smaller than courtyard

Covered section with a central aisle and 2 aisles on each side running

perpendicular to the back wall

7 bays of vaults

DESCRIPTION

This han is perhaps the best preserved of all Anatolian hans, and is

one of the most monumental examples of Seljuk architecture. It is especially

famous for the relief sculpture on the walls of the tomb and on the pillars of

the external walls. Unlike many hans, it contains sections for specific

functions (a mosque, a bath, an infirmary, a mausoleum), which entailed initial

planning of the physical layout and operating expenses, all of which are

enumerated in its foundation deed.

The han is oriented north-south. The structure consists of a covered section used for lodging, built first, and an open courtyard lined with service facilities. The courtyard is twice the dimension of the covered section. The entrances to both sections face south.

The plan is very similar to the Kayseri Sultan Han in size and dimensions but it displays slight variants:

- The courtyard is entirely open, with

the mosque placed in a room to the right side of the entry passage

- the courtyard arcades to the east are

open

- to the left of the entry passage is an iwan containing a burial tomb chamber

whose exterior is decorated with a rectangular frieze comprising a rich and

varied design repertoire carved in high relief: geometrical motifs and animals:

birds, lions and, astonishingly, an elephant.

Visitors first encounter the impressive main portal and the astounding iwan that lies behind it.

Main crown door: The elaborate frames of the doorway contrast sharply with the starkness of the surrounding walls, and thus draw full attention to the monumental portal. The main crown door entrance to the han is located on the southern facade and extends 2.5 m. out from the façade at the corners. It measures 46 by 80 meters, and is flanked on either side by grooved and knotted pillars. The ornate combination of figurative, floral, vegetal and geometric patterns on this portal is unusual. The crown door is composed of a hood of nine rows of stalactites, each with different borders. The crown door opening is surrounded by five borders with different geometrical shapes and blank strips connecting the borders together. The outermost border is formed by a pattern of interlocking T-shapes placed horizontally. The second border is the widest of the crown door, and includes a series of interconnected, twenty-sided polygons. The third border consists of a chain of horizontal zigzags placed one on top of the other. The fourth border is empty, with a section facing towards the interior of the crown door consisting of two intertwined half-stars.

A semi-circular column, covered with interlacing patterns, is located on each side of the crown door opening. The lower section of the column capitals consists of a 24-sided cube. The sides of the capitals facing inwards are covered with figures: a rampant lion on the right side and birds on the left side. The birds once included a peacock, which was visible in old photographs, but the stone has now eroded. The surface of the arch above the columns is decorated with one of the most unusual ornamental compositions in Turkish Seljuk art, consisting of curved vegetal branches intertwining with rumi (split-leaf) motifs and lotus flowers, with a figurative element of ox heads and small human figures in the middle of the vines. Although the figures are in poor condition today due to erosion of the stones, they can be clearly seen in the photographs published by Roux.

More human heads can be seen on the left side of the main door, where two heads are placed within the branches of vegetal decoration. A rosette is located on the surface of each spandrel of the crown door.

A marble inscription plaque is set at the top of the middle of the crown door. The inscription panel, recessed from the crown door surface, is surrounded by rumi elements connected to each other by circular lines. The inscription panel, composed of five pieces of marble, is rectangular at the bottom and the upper section terminates in two lobes.

A rosette with a 24-sided polygon is inlaid in the center of the arch forming the crown door opening and the frame. Above the crown door opening, rosettes are placed between the prisms under the stalactites; two between the prisms on each side and five on the facade. Each of these rosettes is decorated with a different pattern, including the Seal of Solomon, pinwheels and vegetal motifs.

The interior faces of the crown door include semi-hexagonal niches with four rows of stalactites. The outermost section of the niche is framed by spirals, and two different rectangular panels are set above a geometric composition of various interlocking elements, such as 16-sided polygons, lattices, hexagons, rumi split leaf elements and knots.

Entrance iwan: Once you go past the main door, you enter a long vestibule with a unique set of elements which make this han like none other. A deep iwan, located just after the main entrance to the han, leads into the courtyard. The different open and closed service sections of the han open onto this rectangular space. These include a mosque to the right, and rooms for personnel and a tomb to the left.

Eastern (right) side of entrance iwan: A flat, arched door on the eastern side of the entrance iwan gives access to a square space which is covered with a barrel vault in the north-south direction. To the east of this room is another small square room, whose purpose has not been determined. Considering the low ceiling, it might have served as a depot, where the valuable items of the han were stored.

Mosque: The mosque is situated at ground level in the entryway of the courtyard, to the east (right). It consists of a small domed square room, 4 x 4m, with a mihrab decorated with stalactites and rosettes. The door to the mosque is a mini crown portal, surrounded by two borders decorated with braids, polygons, knots and T-shapes. The arch spandrels of the door are filled with circular rosettes filled with vegetal and rumi and engraved letters spelling out "Allah" interspersed in front of them. In the foundation deed, Karatay prescribes that in the place of oil lamps, the usual means of lighting in these buildings, that candles were to be lit all year round from sunset to the morning prayer.

The mosque space is covered with a dome consisting of five sequential rows of stalactites in corner squinches. Above these is a series of 16 triangular prisms and octagons forming an additional two rows of stalactites. The mosque has a skylight in its roof arranged so that worshippers would be able to tell the time. It has its own smaller door opening into the courtyard. A single staircase in the western part of the south side of the courtyard provides access to the roof. Originally the roof was covered with compressed arch but this was replaced during the repairs of 1958-62 with cut stone pavement.

Western (left) side of the entrance iwan: Located here are three openings leading to diverse rooms. The first opening is a flat arched door which gives entry to a rectangular space extending in the east-west direction and is covered with a pointed vault that extends in the same direction.

The middle opening leads into a narrow corridor arranged in the shape of an iwan. This corridor, covered with a pointed vault, leads back into various spaces on the southwestern corner of the han, the first of which is a room in the shape of a reverse L. Although illumination of this area is provided by some skylights at the top of the vault, it is still very dark inside. This L-shaped section gives access to another dark, square room in the corner, which is covered with a barrel vault. It is not clear what purpose these areas to the west of the service area served. It has been suggested that they were used as a sort of municipal town hall. However, the presence of the corridor and guard rooms suggest that the area may have been used a special guest house or maybe even the treasury for the safekeeping of valuables.

Tomb: The most interesting space on the left (western) side of the entrance iwan is the tomb. A third and last opening on the left side, surmounted by a pointed arch, leads directly into a tomb covered by a groined vault.

A tomb is a rather unusual addition to a caravanserai, and this one is heavily decorated with tiles and the frieze of animals. It is not known to whom belongs the sarcophagus located in the tomb. Some researchers have suggested that the cenotaph may belong to Celaleddin Karatay himself. Although he was ultimately buried in his Konya medrese, he may have not intended it to serve as his mausoleum, preferring this room as his burial place. This tomb in all likelihood dates from the Ottoman period.

The first section of the tomb is covered with a pointed vault and the section behind it is covered with a cross vault with stalactites in the center. A star pattern in blue to mimic the heavens is painted on the vault of the tomb above the unmarked cenotaph. In addition to the painted star pattern, the room has exquisite brickwork patterns.

The exterior of this tomb is decorated by one of the most astonishing decorative elements seen in Turkish Seljuk art. The door to the tomb has an arch over the entry. The exterior of this arched opening is ornamented by a cornice of three rows of stalactites. Below this cornice is a marvelous frieze of seventeen niches containing 15 animal figures, including a bird, a deer, a rabbit, a dog, a snake, a wolf, two feline quadrupeds, a bull and an elephant. The borders of the cornice are made up of a geometric mesh of eight-sided polygons, filled in at various parts with vegetal and floral compositions.

The delights of this door are not finished once you step into the courtyard. Once you walk out into the courtyard, turn around and look at the rear face of the main portal. The main portal of this han shows a twist: what is certainly the most powerful decorative element of the entire decorative program is placed on the other side of the main door, the side which faces the courtyard. And what an element it is: a stunning, stylized ribbon of two confronting dragons along the iwan arch. Their bodies are intertwined in a guilloche braid which ends with the dragons heads confronting each other in a roar, their teeth flashing. The dragon, a symbol for wealth and bounty, is mentioned often in astronomy and cosmology texts of the 13th century. The dragon figures indicate the importance paid by the Anatolian Turks to the astronomical sciences. A similar ribbon of dragons can be seen above the door of the Baghdad Talisman Gate (1222), now destroyed but known via excellent photographs taken by Sarre and Herzfeld, and its presence here shows indicates that this symbol had significance in Anatolia as well. Similar dragons can be seen at the Susuz and Sultan Han Kayseri.

Courtyard: The rectangular courtyard of the han is situated to the south of the covered section and slopes in the north-south direction. It is slightly wider than the covered section. The courtyard comprises an open arcade on the western side, covered spaces on the eastern side, and the entrance iwan on the south side with a wide range of rooms.

Western (left) side of the courtyard (arcade): The arcade on the western side contains seven spaces in a row, each carried on two piers and covered with a pointed vault. Six rows of support sections are connected to each other with pointed arches. The first section in the south and the last section to the north are narrower than the others. This vaulted arcade was used as a depot, bazaar and stabling area for animals. Many of the stones have holes for tethering animals, and there are feeding troughs in the side aisles.

Eastern (right) side of courtyard: The eastern side of the courtyard contains seven enclosed spaces. The seven units located on this side are each covered with a barrel vault and have entries surmounted by flat (horizontal) arches. The two units on the north are windowless. Next in line are two units side by side, each with separate entrances from the room to the north of them, not directly from the courtyard. The unit closest to the courtyard is quite small and is covered with a vault in the north-south direction. The space next to it is oriented east-west and is covered with a pointed vault in the same direction. It is believed that these two small rooms were reserved for dignitaries, and the room immediately to the north of them, opening directly onto the courtyard, would have been occupied by guards controlling entry. As such, these 3 spaces form a suite much like in a modern hotel. A group of interconnected rooms such as this are not usually seen in hans, and are believed to have been reserved for special guests, such as the sultan or other dignitaries. The first room, opening directly onto the courtyard, would have been occupied by guards controlling entry, and the remaining rooms would have thus offered greater privacy for the special guests.

Immediately south of these twin small rooms are three rectangular spaces of equal size, each covered with a pointed vault in the east-west direction.

Completing the layout of this eastern side of the courtyard is a distinct section with a rabbit warren of separate spaces in the southeast corner. Some of these spaces are interconnected via a narrow corridor. The rectangular section in the southeast corner is covered with a pointed vault extending in the east-west direction. Within this space, there are anchors projecting at regular intervals along the wall surface, and which probably served to connect a wooden partition to the wall. The presence of traces of a drainage channel on the floor suggests that this area may have been used as the latrine of the han. Other researchers believe that this area was thought to have served as the infirmary, although there was no appointed doctor mentioned in the personnel lists of the foundation document.

Bath: Tucked into this southeast corner rabbit warren of rooms is a bath. The bath is a series of 3 small rooms, located in the right corner of the courtyard passageway (as it is in the Sultan Han Kayseri). The bath consists of an interconnected suite of rooms including a square dressing room, the caldarium (hot room), two private cubicles for disrobing and a water tank. The square dressing room is illuminated by three skylights in the dome. From here, the dressing room door leads south into the caldarium. This space, in the shape of an iwan, is covered with a dome with stalactites. Five round openings in the dome provide light to the space. Traces of water pipes are visible on the south walls of the caldarium, as well as a wall fountain behind them. There are two private bathing cubicles opening onto the caldarium, one of which is entered through a door to the north and the other through a door to the east. Another private cubicle is located on the northern side, and is covered with a dome on squinches. The interior is lit by three skylights, one in the middle and two on the sides. A small opening to the east of the room is the control window for the rectangular water tank.

The bath here is unusual, and, once again, could have been reserved for special guests only and not the general visitors. This courtyard interior bath is quite small and could not have served all of the travelers in this large han, which leads scholars to believe that it was indeed a private bath for dignitaries. Despite the ritual obligation of cleanliness in the Muslim tradition, baths were not common event in the large-scale hans, and only a few are known to have had them (Sultan Han Aksaray, Sultan Han Kayseri, Sari, Ak, Ağzikara, Elikesik, and Ertokuş). It is interesting to note that the bath here is not mentioned in the foundation charter, but every type of expenditure was listed in detail.

The corridor in the southeast corner of the courtyard connects to both the bath and the rectangula room covered with a pointed barrel vault adjoining the the baths. This room was thought to have served as an infirmary; however, there is no physician listed among the staff of the han in the foundation deed document.

This han is one of the two (the other is the Ağzikara Han) examples of hans with both exterior and interior baths. In addition to this internal bath, the foundation charter states that another bath outside the han walls was made available to the travelers, but it has not survived.

Crown door of covered section:

The entrance to the covered section is on axis with the main entrance. The crown door of the covered section is positioned at the center of the southern façade. It projects forward from the main bearing wall. It has an elaborate decorative scheme, also seen in many similar Seljuk hans, such as the Ağzikara and Aksaray Sultan Hans.

The crown door frame is in the form of a pointed arch. It has four borders decorated with different geometric patterns. The borders extend downward on both sides of the crown door in a straight line. The outermost border is decorated with a chain motif placed between two fillet mouldings. The next border has half-stars, followed by a wide border formed of regularly-spaced, star-shaped 18-sided polygons.

The arch of the door opening is fitted with three rows of stalactites. The door opening is framed by semi-circular columns, with capitals in the shape of 24-sided cubes. Two opposing, half-hexagonal niches are placed on each side of the inner surfaces of the crown door. Rectangular panels are set above the niches, and consist of geometric elements which end with three rows of stalactites. A rosette with a braided decoration is set in the corners of the arch above the crown door. In addition, the ghost of one rosette can be seen on the keystone. These rosettes are set in a triangular fashion. In addition there are rosettes on the sides, which are filled with polygonal elements.

The inscription plaque, placed in the center of the tympanum, is framed by a border of half-star motifs. It has an arched profile at the top, and is made from two pieces of marble. Rosettes are seen above the inscription panel on each side, and, an additional rosette is located below it. These rosettes are decorated with eight-sided polygons. The narrow arched doorway is made of interlocking stones.

Covered section: The covered section of the han was built first, before the courtyard. As indicated by the information provided in the inscriptions, the time difference between the construction of the covered section and the courtyard was not long. The tall, main covered section at the end of the courtyard was used as winter quarters. The covered section consists of seven aisles extending in the east-west direction and is formed by two support rows on either side which are carried by two piers. The central nave, running in the north-south direction, is covered with a pointed vault. The seven aisles are covered with pointed vaults extending from the side walls towards the central nave. The piers of the vaulted aisles, which form the support system, are connected to each other with lower arches in the east-west direction. The piers stand on profiled consoles, which carry ribbed arches supporting the vaults of the central nave. A loading platform area exists in the covered section, except in the central nave and the area to each side of it. Prior to the restoration, the area underneath the arches had a series of stone basins, probably for fodder and water for the animals. These feeding troughs and the piers have holes for tying up the animals.

The middle section between the third and fourth piers is shaped like a dome on the interior and appears as a conical lantern dome on the exterior. The lantern transition is made by squinches formed of stalactites. The dome has small porthole window openings located in the four main directions.

Lighting is provided by slit windows on the eastern wall facing the first, third, fifth and seventh aisles, and by windows on the western wall facing the middle of the second, fourth and sixth aisles.

EXTERIOR

This is a massive and noble building, with in total 6 corner towers and 12 side towers. The han resembles a fortress from the outside, with its massive walls and different shapes of reinforced turrets. The exterior walls of the courtyard section are reinforced by 10 support towers; octagonal in the north, star-shaped in the southern corners; one polygonal and one circular in the middle of the east and west facades and two circular ones on the southern side. The pointed-arched opening in the south of the east facade is the stokehole for the baths inside.

The exterior of the covered section was reinforced with two support towers were placed on each of the north, east and west walls of the covered section to reinforce them, but they do not align with the arches. The towers on the southern ends of the east and west walls are in the form of a half octagon, while the others are rectangular. In addition to these, there are square support towers at the corners of the northern wall.

The impressive decoration of the exterior walls includes rainspouts in the shape of winged lions holding a serpent in their mouths, as well as other rainspouts in the shape of human figures.

The walls and the sculptures of this han often served for target practice by locals. In the 1980s, it was noted that the stonework of the walls was peppered by bullet holes and parts of the carved relief work in the upper part of the inner portal had also been fired upon. This damage has been repaired in the recent renovation.

BUILDING MATERIALS

Smooth-faced stones were generally used in the construction. The walls are built using the rubble wall masonry technique, which consisted of filling two rows of smooth-face stones with a mixture of small pebbles and mortar. The mason marks seen on many of the stones of the building are noteworthy.

Foundation deed: One of the most interesting elements of this han is the Foundation Deed that has been preserved intact to this day. The foundation charter, which is still preserved, is an important document, for it spells out the daily operations of the Karatay Han, and thus, by extension, provides valuable insight on how other hans functioned at this time. The foundation deed is dated 1247-48, seven years after the presumed termination of the construction work. The Karatay foundation document provides many administrative details, including the salary scale of the hans employees, expenditures for food and heating oil, and the inventory stock. The listed staff of the han included a trustee and his assistant, a superintendent, an imam, a muezzin (chanter to prayer), a greeter, the han keeper, a cook, a veterinary, a cobbler and a stableman. he endowment deed of Karatay Han states that it was built to serve both commercial and social functions. It provides ample information concerning the commercial and social setup of the han structure. It clearly sets out the services to be provided by the han to visitors, such as food and drink (1 kg of bread and 250 grams of meat per day, as well as honey halva on Friday nights), soap, medicines, provision of leather for the repair or replacement of shoes, nails for the shoeing of animals, firewood for heat and candles and oil for light all for free. Hay and barley were to be provided to the animals. It stipulated that olive oil and wood was to be burned for heating, and that the mosque be lit by candles from sunset until the morning prayer. The personnel lists include a trustee and his assistant, a superintendent, an imam, a muezzin, an attendant to welcome the guests, a supplies officer, a cook, a veterinarian, a stable master and a cobbler. it also lists the kitchen battery (50 large bowls, 20 copper dishes, 100 large-size wooden bowls, 50 wooden dishes, ten large copper pans, 5 medium copper pans and 5 small copper pans, two large basins, two large cauldrons, two large mortars and other cooking utensils). This was a substantial kitchen and could turn out many cooked meals of Seljuk specialities. The document also stated that the han and its pavement were to be maintained. It also stipulated that any person who fell ill on the road or in the han was to receive medical treatment, and in the case of death, the expenses for the washing of his body, shrouding and burial were to be covered. The deed also prescribes that all comers, Muslim and non-Muslim, free or slave, man or woman, be treated equally.

DECORATION

Seljuk era buildings display rich decorative programs, especially on crown doors of hans, city walls, and bridges. The Karatay Han displays some of the richest figurative programs in Seljuk art.

There is much decoration to be seen here at the Karatay Han, which stands out for three decorative programs in particular:

1. Animals: The decorative program of animal and human figures on the crown door, which includes two birds on the column capitals, two wild beasts, three human heads in the borders, two or three hidden human silhouettes, four harpies, two confronting dragons above the courtyard iwan, is quite rich. These figures are in addition to the regular array of decorative elements of geometric (polygons, rope designs, knots, chains, braids, arabesques) and vegetal elements seen on many han crown doors. Exceptional as well are the animal figures on the column capitals of the crown door. On the first capital, a rampant lion rears on its hind legs with its tail curled over his back. Lion motifs are seen on other Seljuk Hans, such as the Alay, Ak, Çardak, Cay, Incir, and Kesikköprü Hans. Birds are also noted at the Ak Han, and the Sultan Han Kayseri dragon on the kiosque mosque is well-known. The depiction of animals is common in pre-Seljuk art and is often related to astrology and other myths. A border runs along the right side of the crown door above the columns, and includes a bulls head at the bottom and a human face at the top. The bull is a shamanist figure of the pre-Islamic period of the Seljuks, and is considered to be the celestial origin of the Seljuks. Bull heads can be seen on the façade of the Ulu Cami in Diyarbakir. One can only wonder why such a rich array of animals is displayed on the Karatay Han. Personal preference of Karatay? Expression of the ancestral beliefs of the Seljuks?

2. Human figures: The high relief gargoyle-like downspouts on the facade. The human downspout on the front of this building to the left of the crown door is legendary. Its head has been broken off, but the body is intact. One of his hands appears to be clutching something to his chest, while the other rests on his right leg. The figure is wearing a tunic, as designated by carved lines on the surface of the stone. He appears to be squatting. Figures such as this are seen in Seljuk art, especially on the series of tiles made for the Kubadabad Palace, which are decorated with a wide array of human figures. The Susuz Han is the only other han to depict human figures. Two gargoyles on the entrance facade are in the form of dragon heads. One of them was removed during the restoration and installed in the arcade section. Two confronting human silhouettes can also be seen on the border on the left side of the crown door. These probably represent female figures, but this cannot be ascertained today due to erosion of the stone.

3. The row of 15 animal figures carved in the stalactites above the entrance to the tomb in the iwan. In addition to these figures, two confronting dragons are seen at the top of the iwan, with their bodies extending along the arches of the iwan. The Karatay Han is undoubtedly most famous for the enchanting "parade of animals" frieze above the tomb with its decoration of human and animal figures: their presence may be attributed to the long-standing tradition of shamanism. These figures could represent mythological creatures, which are frequently seen in Turkish art, and have their origin with the 12 animals of the Central Asian Turkic Uygur animal calendar. The Carnival of the Animals parade of 15 figures at the entry of the Karatay Han is a masterpiece and includes one very unusual animal for the middle of Anatolia: and elephant. What must tired caravans thought when they crossed the threshold of this han and found themselves in an entryway worthy of a palace, and looked up to see this parade of animals escorting them in? How many of these travelers even knew what an elephant was? Only three elephants are known to be represented in Seljuk art: here, on a stone from the Konya city walls (in the İnce Minareli Medrese Museum of Konya), one on a glazed tile from the Kubadabad kiln and used in the tepedarium of the Hunat Hatun Baths of Kayseri, now housed in the Güpgüpcüoğlu Ev Ethnography Museum in Kayseri (although its whereabouts are currently unknown) and here in this frieze in the Karatay Han.

DIMENSIONS

Total area: 3,025 m2

Area of

covered

section: 815m2

Area of courtyard: 1,760m2

This is the fourth largest Seljuk han.

STATE

OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

It appears that the Karatay han became a zaviye (dervish lodge), as per a 15th century document. The building has undergone two major restorations, in 1964 and 2009. During the restoration in 1964, the geometric decorations and missing parts of the main crown door and the niches were filled in and repaired. The covered section crown door was unfortunately altered during the restoration project of 1964, other patterns were added without respect to the original design layout, and the 18-sided polygons at the center were shifted to the side. The innermost border of the door comprises concentric circles with knots skewed toward the interior of the door. While the circle on the outermost side is composed of a larger knot motif, smaller circular knots fill in the composition on the sides. Furthermore, after the restoration of 1964, the walls and crown doors were unfortunately adversely affected by a leak caused by faulty installation of the top cover roofing, which led to surface damage to the crown doors and erosion of their decorative elements. In 2009, the courtyard was arranged to resemble a park and lighting poles and fixtures were installed, which regrettably mars the original architectural integrity of the building. These objections aside, the Karatay Han is in excellent condition, and is probably one of the best preserved of all the existing hans today.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Aksarayi, Mehmed ibn Kerimüddin Mahmud. Selçuki Devletleri Tarihi (Müsameret-al-Ahbar). Translated by M. Nuri Gençosman. Ankara: TKK, 1943.

Altun, Ara. An Outline of Turkish Architecture in the Middle Ages, 1990, pp. 199-200.

Aslanapa, Oktay. Selçuk Devlet Adamı Mübarüziddin Ertokuş Tarafından Yaptırılan Âbideler. İslam Tetkikleri Dergisi, II/1, 1957, pp. 97-111.

Bar Hebraeus (Gregory Abul Farac). (2003). E. A. Wallis Budge, trans. The Chronography of Gregory Abul Faraj. Piscataway, NJ. , I: 413.

Bektaş, Cengiz. Selçuklu kervansarayları, korunmaları ve kullanılmaları uzerine bir öneri = A proposal regarding the Seljuk caravanserais, their protection and use, 1999, pp. 122-127.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 2, pp. 205-213.

Blessing, Patricia. Rebuilding Anatolia after the Mongol Conquest: Islamic Architecture in the Lands of Rum, 1240-1330. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2014, pp. 177-78.

Dentaş, Mustafa. Karatay Hanı. In Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı, 2007, pp. 358-379 (includes extensive bibliography in Turkish).

Deniz, Bekir. Ağizkara Han. In Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı Publications, 2007, p. 331.

Eravşar O. Seyahatnamelerde Kayseri. Kayseri: Kayseri Ticaret Odasi, 2000.

Eravşar, Osman. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara Kültür Bakanlığı, 2007.

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 394-409.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961, pp. 117-125, no. 32; vol. 3, pp. 148-152.

Ertuğ, Ahmet. The Seljuks: A Journey through Anatolian Architecture, 1991, pp. 82-95.

Gabriel, A. Monuments turcs d'Anatolie, I, II. 1931, 1934, p. 112.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 508.

Gierlichs, J. Mittelalterliche Tierreliefs in Anatolien und Nordmesopotamien. Tubingen, 1996.

Gülyaz, Murat Ertuğrul, "The Kervansarays of Cappadocia", Skylife Magazine, December, 1999.

Halil, E.B. Einige Islamische Denmäler Kleinasiens. Studien zur Kunst des Ostens, 1923, pp. 243-247.

Karpuz, Haşim. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, vol. 1, pp. 475-477.

Koman, M. Karatay Kervansarayı [Karatay Kervansaray] in Konya 1941, 35/5, pp. 3026-33.

Kuban, D. Selçuklu Cağinda Anadolu Sanati, 2002, pp. 244-249.

Moltke, H. Briefe über Zustände und Begebenheiten in der Türkei aus den Jahren 1835 bis 1839. Berlin, 1841.

Ögel, S. Anadolu Selçuklarin Taş Tezyinati, 1966, p. 29.

Öney, G. Anadolu Selçuk Mimarisinde Boğa Kabarmalari. Belleten 34 (133), 1970, pp. 83-100.

Özbek, Yıldıray & Arslan, C. Kayseri Taşinmaz Kültür Varliklari Envanteri. (Vol. 1-3). Kayseri, 2008.

Özergin, M. Kemal. Anadoluda Selçuklu Kervansarayları, Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, pp. 154, n. 84.

Redford, S. (2015). "Intercession and Succession, Enlightenment and Reflection: The Inscriptional Program of the Karatay Madrasa, Konya" in A. Eastmond, ed. Viewing Inscriptions in the Late Antique and Medieval World. Cambridge:, Cambridge University Press, 148-169.

Redford, S. Reading Inscriptions on Seljuk Caravanserais. Eurasiatica 4, 2016, pp. 221-233.

Roux, Jean-Paul. Le décor animé du caravansérail de Karatay en Anatolie. Syria 49 (3), 1972, pp. 377-379, 382.

Sterrett, J. The Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor during the Summer of 1885. Boston, 1888.

Sümer, F. Yabunlu Pazari, an Important International Fair during the Saljuk Period. Istanbul, 1985, pp. 80-81.

Turan, Osman. "Selçuklu Kervansarayları. Belleten, X/39 (1946), pp. 471-496. (includes the translation of the text of Qadi Muhyiddin Ibn Abduzzahir, and the information on the 15th c. zaviye)

Turan, Osman. Selçuk Devri Vakfiyeleri. III Celâleddin Karatay Vakıfları ve Vakfiyeleri, Belleten, XII, 1948, pp. 17-171.

Ugur, M. Ferit and M. Mesut Koman. Karatay Kervansarayi in Konya 35 (1941), p. 3027.

|

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

The photos below were taken in 1963 by John Ingham:

|

|

|

|

|