The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

KIZILOREN KANDEMIR HAN

This han presents a rare variant on the habitual crown portal: here the entry door is flush to the façade and is framed by a distinctive white stone arch. A second storey mosque built into the courtyard entry, an inscription facing the courtyard and an outbuilding to the rear are other distinctive features of this han, one of the oldest known.

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 164; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

front view (pre-2008 restoration) |

|

Photograph (G019) of the han taken by Gertrude Bell in May, 1907 |

|

4 line inscription, now missing, photographed by Riefstahl in 1930. |

|

The plan of the han drawn by Erdmann, showing the second story group of 3 rooms and the adjacent outbuilding |

|

courtyard view looking to entrance, with second storey mosque on the right |

|

iwans on north side of han, looking towards covered section |

|

same view, before the renovation Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.2, p. 132 |

|

courtyard iwans, southern side, before renovation |

|

courtyard, looking towards the covered section door (pre-renovation) |

|

same view (pre-renovation) |

|

|

spolia lintel in courtyard |

|

stairs to upper level mosque |

|

|

DISTRICT

42 KONYA

LOCATION

37.888502, 32.147200

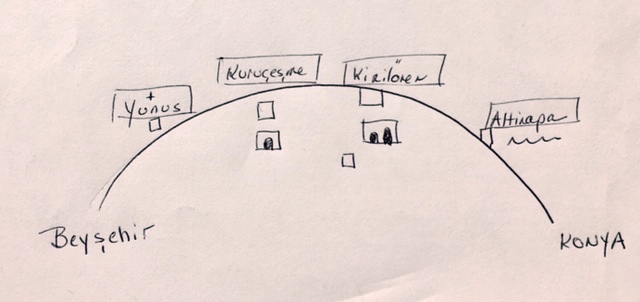

The Kizilören Kandemir Han is built on the northern slope of a small bluff in a mountainous area 34 km from Konya on the Konya-Beyşehir caravan route, in the Suleiman Demirel Memorial Forest. İt is located about 200m south of the road. It is one of the series of four hans originally built along this stretch of road. These include, starting from the Konya direction westwards: the Altinapa Han (now submerged by the waters behind the Altinapa Dam), the Kizilören Han, the Kuruçeşme Han, and the Yunuslar Han (mentioned in sources, but whose traces have been lost).

The modern highway was laid parallel to the historic caravan route and has covered over most of its original traces. The road that the han was built upon followed the path of the 1,000 year old Via Sebastia that the apostle Paul traveled on four times (twice on his First Journey (heading east and then returning west), and on his Second and Third Journeys (both times heading west).

The existence of four hans in such a short proximity shows the vitality of the trade along this route leading to the capital city of Konya in the Seljuk period.

OTHER NAMES

Hanönü

Emir Kandemir Han

Kizilviran

Yazı Han, Yaziönü Han

The name means the han of the "Red Ruins", probably due to the fact that the stone has a distinctive reddish cast.

Much confusion exists in academic literature concerning the name of this han and its neighboring han, the Kuruçeşme Han, over the years until the present. This confusion stems perhaps from the fact that the two hans are so close to each other and that the village of Kizilören is located between the two of them. Furthermore, the Kiziloren Han has a second building near to it. Pace in 1926 called the Hans Kizilören #1 and Kizilören #2, and he is perhaps the clearest in this sense in relation to the village of Kizilören. Erdmann, Yavuz and Karpuz call this one the Kizilören Han, while Bektaş and Kuban label it as the Kuruçeşme Han. Gertrude Bell, who visited the region in 1907, has left two good photographs of the han (G19-20), which show a well in front of it. She labeled her photos as Kizilören. She said that the han is known by the locals as the Emir Kandemir Han, because this name was mentioned in the inscription. The han is referred to as the Yazi Han in some Ottoman sources.

To make a stab at clearing things up, the local government stepped in. Since 1953, the official name of this han in administrative records is the Hanönü Han. This name means The Preceding Han"; given to avoid confusion with the Kuruçeşme Han, 10 km farther down the road towards the west towards Beyşehir.

Following the renovation of this han, a large sign framed in blue and written by the Turkish Foundations Directorate was set up in the grassy lawn in front of the han. This sign states Kizilören Han. In addition to this sign, a fancy gold plaque was affixed to the left of the entry door of the han, which states Emir Kandemir Han. The Han is currently run as a restaurant and equestrian club, whose Facebook page calls the han the Kizilören Atli Han. The locals call this han the Emir Kandemir Han.

INSCRIPTION

The han currently has no inscription. However, it is known that the han once had an incomplete inscription of nine lines in naksh calligraphy, but it has, alas, gone missing over the years. It was in place in the 1980s but it is believed that it was stolen at this time. Pace saw the inscription in 1926 but declared it illegible. Later, the Austrian Orientalist Paul Wittek found a photograph of the inscription in the archives of Riefstahl, and read the inscription for Erdmann. This original photograph as well appears to have gone missing. He also indicated that there was a circular section at the top of the inscription. The inscription did not include the date of construction, the names of the patron or he who commissioned it. However, Wittek read this among the nine lines of Arabic: "Built during the reign of Kılıçarslan bin Keyhüsrev, the sultan of lands and seas..." The mention of the "seas" is most certainly a reference to the brilliant capture of Antalya by Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev I in 1207. Since then, the inscription has been published by R. Oğuz Arık, who reads the four lines as follows, and notes the name of the patron:

"Built during the reign of the Great Sultan, the Sultan of the Arabs and Persians, the hero and the deputy of the Commander of the Believers, Keyhüsrev bin Kılıç Arslan. Emir Kandemir has ordered this han to be built in the month of Muharram, 603."

It is significant to note that this inscription was not placed on the entry door, but rather on the side facing the courtyard, which is an unusual emplacement for an inscription plaque. Inscriptions were always put on the front of the han door to herald the power and prestige of the sultan and patron to all those entering. The reason for placing the inscription here and not in the habitual exterior emplacement has not been understood.

DATE

1205-6

(dated by inscription)

This han is one of the earliest dated Seljuk hans. This date corresponds

with the construction in the same period as the other hans along this route,

between 1207 and 1210. It is remarkable to see two hans (Kuruçeşme and Kızılören)

built so close to each other (10 km apart), on the same route and at the same

approximate time.

REIGN OF

Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev I

REIGN OF

Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev I

PATRON

According to the inscription, the Kizilören Han was built during the reign of Sultan Gıyaseddin Keyhüsrev I and was commissioned by Emir Kutluğ bin Muhammed (Emir Kandemir), an emir serving the sultan, in 603/1207.

BUILDING TYPE

Covered with open courtyard (COC)

Covered section smaller than the courtyard

Covered section with 1 central aisle and 1 aisle on each side running perpendicular to the back wall

6 bays of vaults in the central aisle; 3 in the side aisles

The courtyard has 4 open cells on each side.

DESCRIPTION

This large han

was built on a slightly inclined terrain and the han door faces towards Beyşehir.

The han has the classic covered section plan used for lodging and an open

courtyard with service spaces. The courtyard is slightly wider than the covered

section.

This han is the first example of the most frequent type of plan, which is that of a covered section with a wider courtyard. This han and the Altinapa Han, the one directly to the east along the Konya-Beyşehir road, are the earliest examples of this type of the courtyard and covered section plan. However, the plan of this han shows several variations not normally encountered in both the courtyard and the covered section, such as the second storey mosque in the courtyard and the two wings at the entry of the covered section.

Main portal and entrance block:

The courtyard main entry portal is 3.24m wide and is framed by a distinctive white round arch. On the north (left) side of the main entrance is an iwan-like area open to the front and closed to the courtyard, forming what looks like the smaller opening on the façade of the han. It is covered by a cross vault and probably served as an area for the guards on duty. This space and the water system below the mosque were destroyed by scavengers before the restoration.

The interior side of the entrance door (facing the courtyard) is more elaborate than the exterior side. On this side the door has a recessed panel under the arch where the inscription board was set facing the courtyard, a very unusual placement of the inscription plaque. This inscription has been lost. Remains on the southeast wall of the courtyard side indicate the presence of a fountain niche at this spot.

Both crown doors are designed flush with the bearing walls. There are other examples of this design feature, such as the Pazar Hatun and Cirgalan Hans, although it is not widely seen in Anatolia. Doors usually project from the main wall.

The facade is designed as an independent block with three sections and two floors. The entrance to the han is not just a mere door, but is composed of a large, 2-story block unit which projects into the courtyard. The lay-out of this block is rather complex and is unique among hans. The ground floor of this unit contains two spaces, the one to the left being the iwan opening to the front described above. The cell to the south (right) is covered by a barrel vault in the east-west direction. It is closed off from the exterior and is reached directly from the courtyard. The interior is lit by a slit window. It probably served as the headquarters of the han keeper or the guards. Remains on the southeast walls of this room indicate the presence of a fountain niche.

This entrance block element has an upper level as well. There are 3 rooms in total on the upper level over the entry, with the one to the north serving as a mosque. The upper floors are reached by two separate flights of stairs with a landing against the southeast wall of the entrance iwan. The cantilevered stairs on the left led up to the roof as well. There is a window in each of the rooms on this level, which look out down the road ahead and give the han façade its bespeckled appearance. The room to the south (right) on the second level is connected internally to the room above the entrance. This middle space, due to its protected entry, may have been the treasury.

The room to the north on this upper level was used as a mosque, as indicated by the presence of prayer niche in the Qibla (Mecca) direction. Indeed, this han is also regarded as one of the first experiments in placing of the mosque room above the entrance porch, reached by steps leading upwards. Access to the mosque is through the courtyard via a set of console stairs. It measures 4 x 5.5 m. The mosque is covered with a cross-vault which rests on four pillars; two are embedded in the stone wall and two stand free. On the west side is a pointed vaulted space extending in the east-west direction.

The entrance door and the door to the covered section of this han may be plain, but the mosque door received full decorative treatment. The entry door to the mosque is surrounded by a slightly-recessed border of half stars, followed by a strip of thin lattice elements which continues around the corners of the door opening. Above this, a console-shaped profile carries the arch ledges. The arch surface is profiled in brick with an oval swirling appearance. Decorative attention was paid as well inside the han, where the mihrab is finely-detailed. The mihrab niche was in the shape of a scallop shell, as can be seen in the photograph of Riefstahl. This original mihrab was pillaged by scavengers and destroyed, but was rebuilt during the renovation. Small columns are set in the corners of the mihrab niche with side panels of carved with palm frond elements.

Courtyard:

The courtyard is surrounded by rooms along its long sides. It is 2.6m wider than the covered section and has four open arcades resembling iwans on each side, and which are 6.3m deep. Four symmetric iwans are located lengthwise on each side of the courtyard. The iwans of each arcade are covered with pointed vaults in the north-south direction. The opposing iwans are not connected with each other internally.

Covered section:

The portal leading to the covered section is 2.5 meters wide and has a niche 1.2m deep. It protrudes from the facade and rises above the roofline. The door is framed by plain borders and has a simple pointed arch.

The covered section has 3 aisles, with the central aisle twice as wide as the side aisles. A total of 10 square piers interconnect with the pointed arches of the vaults. The han is covered with barrel vaults in the east-west direction. The covered section is lit by slit windows located between the arches on the southern wall. Two additional slit windows were placed on the north wall during the restoration.

A curious plan element is the two rectangular wings on each side of the western end of the covered section. These are accessed through the arcades in the courtyard, not in the covered section and are covered by a single vault in the east-west direction. The exact use of these two spaces has not been determined, but in view of their entrance layout, they were probably used for storage of supplies. These two spaces were in all probability added later during the Ottoman era.

Exterior:

The interior of the masonry walls, made of finely-cut blocks of stones, were filled with rubble. The stone blocks used on the outer walls are all approximately the same size, except for those of the entrance. Compared to other hans on the route and in the Konya region, reuse spolia materials were used less frequently here. Yellow tufa stone was the material used in most parts. A few pieces of spolia reuse material can be seen in the courtyard, notably a lintel piece carved with the egg and dart pattern.

The courtyard walls are braced by an octagonal tower on each corner of the facade, circular towers on the western corner and square towers in the middle. Both crown doors are designed flush with the bearing walls. There are other examples of this design feature, such as the Pazar Hatun Han, although it is not widely seen in Anatolia. The facade of the han is flanked by octagonal towers at each corner. It is to be noted that the wall near the mosque differs from the walls of courtyard in terms of technique and masonry, and may point to a somewhat later construction. The stones used here are larger blocks in comparison with the masonry of the courtyard. The upper part of the covered section was built using rough-cut stones.

Outbuilding:

The han appears to have been designed integrally with a second independent structure located on a small hill 400m to the southeast. This rectangular structure measures 15 X 21m and has two vaults in its roof. A low-arched doorway leads into the prayer hall. It has two aisles and two floors. Its exterior walls were made of rough-faced stones. The portal resembles a shallow iwan with a portal niche. This building is often considered as a second han, built at approximately the same time. Many believe that it was built as a mosque, as the space contains a mihrab. Erdmann, however, believes the mihrab was added at a later date to turn the building into a mosque for locals. The mihrab, located on the southern wall of the western aisle, is made of smooth-cut stones and is in the form of a semi-circular niche topped with a rectangular frame. Due to the fact that there was a mosque on the second floor of the main han, it seems unlikely that visitors to the han would trundle over here to use this space. It had to have been built for another purpose, perhaps as an additional storage area or as a guard house. Yavuz, who calls the structure the "Second Han at Kizilören", believes that the building was a relay stage for the administrative courier postal system. A similar situation with an outbuilding attached to a han can be seen at the Kuru Han in Kahramanmaraş. This could have also been built as an additional han along the already dense chain along this road; but was probably used for a secondary purpose and not for housing guests.

DECORATION

There is very little decoration in this han. There is no decoration on either of the crown doors, and little in the entire han, except for the mosque on the second floor. The separate outbuilding portal has a strong and attractive triple row of arches.

DIMENSIONS

820 m2

Covered section: 410 m2

Courtyard: 410m2

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

This han stood

in lonely isolation for many years, and was used by locals as holding pens for

sheep and goats. However, its days of obscurity ended in June, 2008, when the

Turkish Foundations Directorate announced that the han would undergo $1.6

million restoration project. Work began in April, 2008. The vaults were

extensively renovated and the surrounding parapet walls were erected during the

project. The bases, arches and superstructure of the northern arcade were

largely intact before the restoration. The arches on the southern side were in

ruins to a large extent. The reconstruction of these parts was carried out in

consideration of the features of the north side.

Since June, 2009, the han serves as a restaurant cum equestrian club. Sit back on the colorful kilim cushions installed in one of the iwans off the courtyard and enjoy a mouthwatering tepsi kebab, a local Konya delicacy, just as did Seljuk sultans 800 years before you when they visited this han.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı Publications, 2007, p. 511

Baş, A. Konya-Hatunsaray-Seydişehir Kervanyolu Uzerine Düşünceler. V. Milli Selçuklu Kültür ve Medeniyet Semineri Bildirleri. Konya, 1996, pp. 141-168.

Baş, Ali. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Konya Kervansarayları. Çekül Sanatsal Mozaik, vol. 3/33, 1998, pp. 60- 69.

Bektaş, Cengiz. Selçuklu kervansarayları, korunmaları ve kullanılmaları uzerine bir öneri = A proposal regarding the Seljuk caravanserais, their protection and use, 1999, pp. 79-81.

Bell, Gertrude. The Gertrude Bell Archives. Internet web document. www.gerty.ncl.ac.uk/, folder G, photos G019-020.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 2, pp. 413-417.

Branning, Katharine. Moon Queen. New York, 2014. Chapter 8, pp. 35-39 (this historical novel sets a chapter with Sultan Alaeddin Keykubad and Mahperi Hatun in this han.)

Demir, Ataman, "Anadolu Selçuklu Hanları. Kızılören Hanı", İlgi, 46, 1986, pp. 8-13.

Demir, Ataman. "Anadolu Selçuklu Hanları. Kuruçeşme Han ", İlgi, 47 (1986), pp. 24- 27.

Demir, Ataman. "Anadolu Selçuklu Hanları. Konya-Beyşehir Arasında Kuruçeşme Hanı", İlgi, 47 (1986), pp. 24-27.

Eravşar, O. Spolia in Seljuk Buildings. in SOMA 2014: Proceedings of the 18th Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology. Wroclaw, 2014, pp. 167-182.

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 164-169.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961, no. 9, pp. 45-51.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 5011.

Karaoğlu, Zeynep Alp, "Konya Yakınındaki Kızılören Han'ın Tanıtımı ve Değerlendirilmesi", I. Uluslar Arası Selçuklu Kültür ve Medeniyeti Kongresi- Bildiriler I (11- 13 Ekim 2000), Selçuk Ünv. Selçuk Araştırmaları Merkezi Yayını, Konya, 2001, pp. 461- 475.

Karpuz, Haşim. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008., vol. 2, p. 131-33.

Karpuz, Haşim. Konya Kizilören Hanı, Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara Kültür Bakanlığı, 2007, pp. 88-103. (Although entitled Kizilören Han, this article discusses the Kuruçeşme Han.)

Kiepert, R. Karte von Kleinasien, in 24 Blatt bearbeitet, 1902-1916.

Konyali, İbrahim Hakkı. Abideleri ve Kitabeleri ile Konya Tarihi. Konya, 1964.

Kuban, D. Selçuklu Cağinda Anadolu Sanati, 2002, p. 239.

Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Konya ve ilçelerindeki Selçuklu Eserleri, 2005, pp. 33-35. (called the Emir Kandemir Han).

Özergin, M. Kemal. Anadoluda Selçuklu Kervansarayları, Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 155, p. 73.

Pace, B. Ricerche nella regione di Conia, Adalia e Scalanova. Annuario della R. Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiane in Oriente, 1923-1926, 1926, p. 392.

Riefstahl, R. Meyer. Turkish Architecture in southwestern Anatolia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931.

Wilson, Mark. Biblical Turkey: A Guide to the Jewish and Christian Sites of Asia Minor. Istanbul: Ege Yayinlari, 2010, p. 170.

Ünal, Rahmi Hüseyin. "Kızılören Hanı Yakınındaki Yapının İşlevi Hakkında Gözlemler." Arkeoloji-Sanat Tarihi Dergisi, VI (1992), pp. 129-136.

Yavuz, A.T. "The Concepts that Shape Anatolian Seljuq Caravanserais", Muquarnas 14, 1997, pp. 80-95.

|

photo of mosque mihrab by Riefstahl

|

|

|

mihrab before renovation |

mihrab after renovation |

|

Photo by Erdmann (#53) (He calls it the Kizilören Han) |

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.2, p.131 |

|

view from courtyard out onto road; with empty inscription board |

Interior courtyard cells, looking from the courtyard towards main entrance, prior to the restoration. The traces of the stairs leading to the second floor can be seen on the right . |

|

|

plan drawn during the renovation project |

|

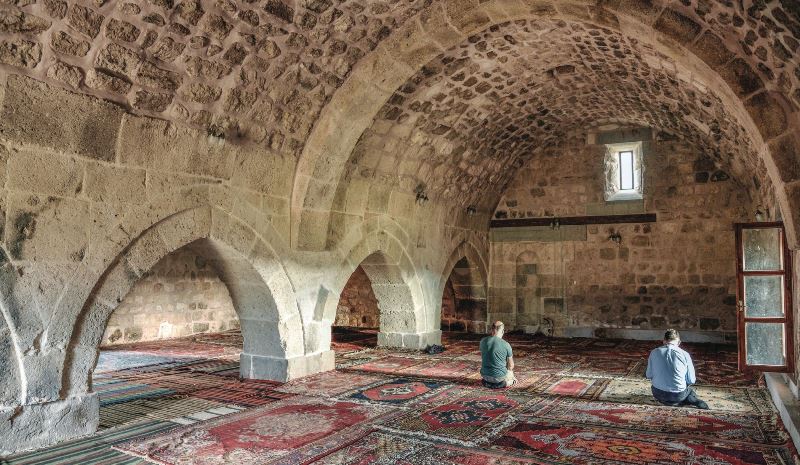

covered section |

covered section

|

|

drawing of entry block facing courtyard by Zeynep Alp Karaoglu |

drawing of facade by Zeynep Alp Karaoglu |

|

outbuilding as seen from the road

|

separate outbuilding to southeast rear of han

|

|

detail of door, outbuilding

|

|

|

|

|

the Konya-Beyşehir Road seen from the han |

|

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 169; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|