The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

ZAZADIN HAN

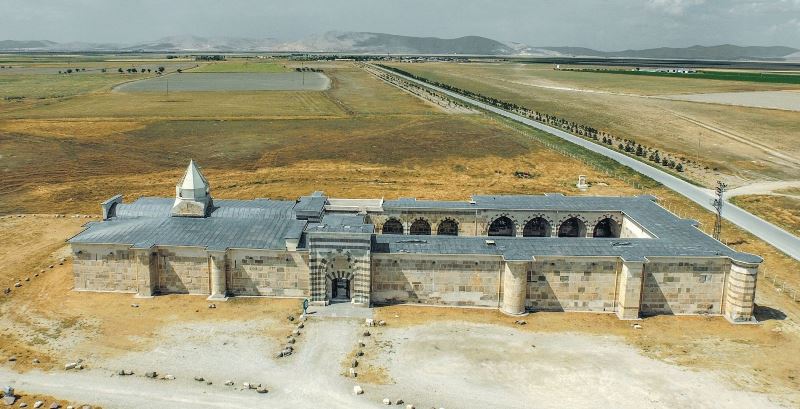

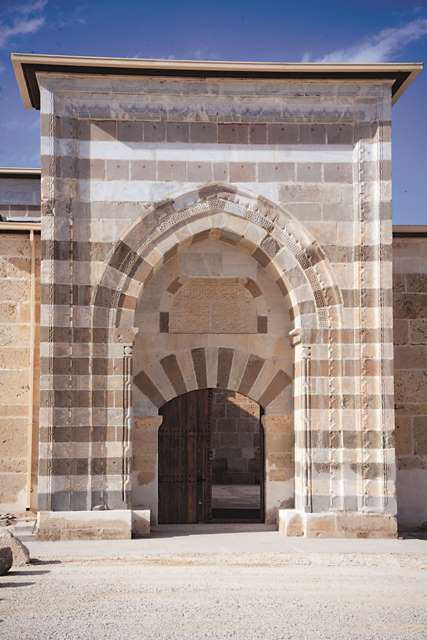

One of the most spectacular hans in Turkey, the Zazadin Han is famous for its off-axis entrance into the courtyard, its two intact inscriptions, its dazzling striped portal, the extensive spolia stones in its walls and the notoriety of its patron and architect, the vizier Sadeddin Köpek.

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.2, p. 86 |

Restored facade as of June, 2008 |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.2, p. 87 |

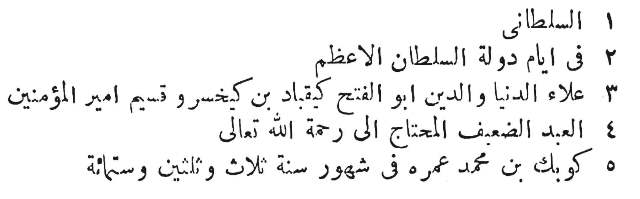

inscription over the covered section door (1235)

|

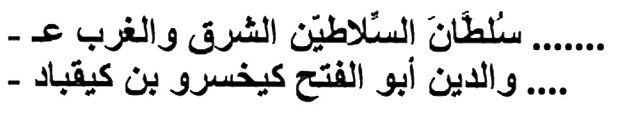

inscription over the main door into the courtyard (1236-37) |

Main entry door (pre-restoration) |

Bilici, vol. 2, p. 495 |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

detail of ropework and sawtooth decoration |

|

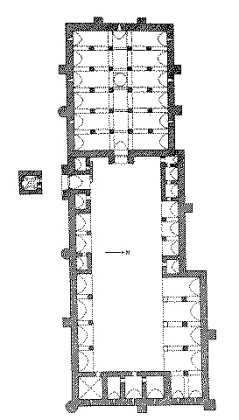

Plan drawn by Erdmann |

|

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.2, p. 86 |

Central nave of covered section, roof now collapsed (pre-restoration 2008; see folders below for other pre-restoration photos |

central nave after restoration |

Bilici, vol. 2, p. 499 |

DISTRICT

42 KONYA

LOCATION

38.0039113, 32.67745

This han is located 20 km northeast of Konya on the Aksaray-Konya Road,

at the turnoff for the village of Tömek. It can also be reached from the Konya-Ankara

Road, outside the village of Kavacık.

The han is built on an ancient burial tumulus slightly to the south of it. This tumulus, has been bulldozed and flattened down and thus has lost all of its historical significance. Other surrounding tumuli have alas met the same fate due to urban development. The local authorities have not shown support for archeological excavations of these pre-historic tumuli, which is regrettable.

The Horozlu Han is the next han in the direction of Konya and the next han in the direction of Aksaray is the Obruk Han.

OTHER NAMES

Sadettin Han, named after its patron, the vizier Sadettin Köpek.

This name is pronounced in the local dialect as Zazadin.

Although the Zazadin Han is located on the important and busy Konya-Aksaray

caravan road, its name is not mentioned in any historical sources. This can be

explained by the fact that the nearby Zencirli Han (now lost) was the preferred stopover

for travelers, who thus took that route and bypassed the Zazadin Han.

DATE

1235 for the covered section and 1237 for the courtyard (as per the inscription).

There are two inscriptions: one over the covered section door, dating from 1236-37 (one year before the death of Sultan Alaeddin Keykubad) and which states that it was built in the time of Alaeddin Keykubad by the Emir Köpek, and the second one over the main door leading into the courtyard door states that the han's construction was started in 1235 by Alaeddin Keykubad and finished by his son Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev in 1236-37.

Construction of the han began during the reign of Alaeddin Keykubad I and was completed one year after his death by his son Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II. The names of both sultans are mentioned in the inscriptions of the crown doors of the covered and courtyard sections. Both of the inscriptions are intact and provide substantial information concerning the patron and the construction date.

The five lines of the carved marble inscription over the crown door of the covered section, built first, are over painted in red, and are written in Seljuk-style naskhi calligraphy. They read as follows:

In the time of Keykubad son of Keyhüsrev, ordered to be Emir of the believers, the duty of Sultans, conqueror, the exalter of the world and the faith, by the poor slave who needs the mercy of Allah, Köpek son of Muhammad (may God bless his life) was this structure built in the months of 633.

The marble inscription over the main entry door leading into the courtyard, on five marble sections, was written in Arabic in Seljuk-style naskhi calligraphy. The uppermost part of the inscription has been lost. The following four lines read as follows:

When the virtue and abundance increased and moved to meet the benefaction, in generosity of the bright state and the mercy of the period of Keyhüsrev the supreme sultan, the great conqueror, the son of Keykubad, protector of the world and the faith; the poor slave Köpek son of Muhammad built this in the year of 634.

Another partial inscription was discovered during the recent restoration. It is exhibited in the Sahip Ata Hanikah Museum of Konya.

REIGN OF

Building started in the last year of Alaeddin Keykubad's rule (1235-36) and was

completed during the reign of his son, Gıyaseddin Keyhüsrev.

PATRON

Seljuk Emir Sâdeddin Köpek ben Mohammed, vizier of Alaeddin Keykubad

I.

This han is famous not only for its architecture, but for its patron and his service to two sultans. The patron of this han is the famous emir Sadeddin Köpek, who is mentioned in many stories and legends in historical sources, notably in the journal of Ibni Bibi and in the text of the French Dominican friar Simon de Saint Quentin. First serving as the interpreter of the Sultan, he then became his architect and emir of the state. In this role he unjustifiably disposed of many emirs, which created much instability in the Seljuk Empire and led to the ensuing period of decline. It is even most probable that he had a hand in the poisoning of the his sovereign, the Sultan Alaeddin Keykubad I.

The

architect is quite possibly Emir Köpek himself, who was principally known as an architect in

the court of Alaeddin Keykubad, and who built the sultan's palace at Lake Beyşehir, the

Kubadabad.

Sadeddin Köpek may have been a dangerous and cruel political agent with an

undoubtedly psychopathic personality, but one thing can be said of him: he was a

superb architect. This building is a masterpiece of Seljuk architecture, whose

elegance, elaborate and supreme design are all indications of the special

attention paid by Sadeddin as both patron and architect. The bright state of

the Sultan, for certain.

BUILDING TYPE

Covered with open courtyard (COC)

Covered section is smaller than the courtyard

Covered

section with a middle aisle with 2 aisles on each side

6 bays of vaults

DESCRIPTION

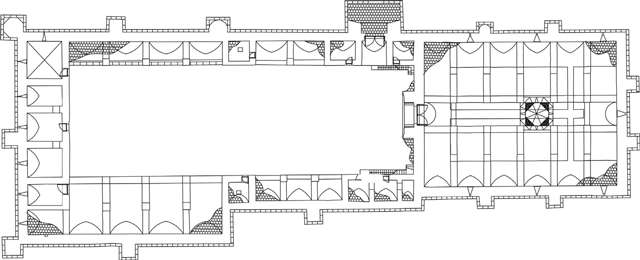

Plan:

The han faces west, and lies parallel to the road, with the door facing Konya. It is built with the common plan type in the 13th century, with two main sections: a covered section for lodging and an open courtyard with service facilities. The courtyard is wider than the covered section and is on axis with the covered section. The main entrance door is placed off-axis to the south.

The unusual features of this han include its broad courtyard and the location of the entrance portal, eccentrically placed on the southern side. It is an exceptionally large han, the 10th largest.

Like the Duragan, Kesikköprü, and Ağzikara Hans, this han has an excentric entrance (the two portal doors are not in the same axis as is generally the case for open courtyard and covered plan hans).

Courtyard:

This is undoubtedly the most interesting courtyard of any Seljuk han. The open courtyard section, two times larger in surface area than the covered section, is situated to the east of the covered section. The entrance is not on axis with the covered section, but is rather on the south side, which is the longest side of the courtyard. Here, the walls of the two sections continue from end to end in one line, and this wall is the longest example found in any Seljuk building. The entrance comprises a small iwan, and the courtyard contains units of different sizes on the north, south and east sides.

The relationship of the very long courtyard and the small covered section give this han a somewhat disproportionate appearance. The long courtyard widens on the northeastern side, forming an elongated rectangle. The spaces along its long sides are of unequal size. There are many different service spaces in this courtyard.

The han's northern part is the open courtyard used in the summer (17 X 54 m). Around the northern side of the courtyard is a sunken area for stabling animals, set apart by a retaining wall. A bath is located in the room in the southeast corner of the courtyard, with a elaborately-carved doorframe and brick squinches. There was also a kitchen-refectory on the northern side of the courtyard, immediately before the section of open arcades.

An arcade extends along the southern side of the courtyard, to the east of this room. This arcade sits lower than the courtyard level. Many broken pieces of tile were found inside these rooms during the excavations of 1996. It is believed that these small covered rooms were reserved for special and prestigious guests, and the room with the tile decoration was most certainly reserved for the Sultan.

Square covered rooms of different sizes and arcades of differing depths are located on the north side of the courtyard. A suite of three small rooms is situated opposite the entrance of the courtyard: two are square and one is a small rectangle. The console staircase giving access to the roof was mounted on the walls of these rooms. The east section of the courtyard consists of four covered and two open units. There is an arcade in the north end of the east section, heading to the bearing east wall. The arcades are lit by slit windows in the east wall. Entry to three of the four covered is from the inside. Interconnected rooms such as these are not generally seen in hans, and are believed to have been reserved for special guests, such as the sultan or other dignitaries. The first room, opening directly onto the courtyard, would have been occupied by guards controlling entry, and the remaining rooms would have thus offered greater privacy for the special guests. During the excavations, pipes were found in the walls of these rooms which were believed to serve as the bath for dignitaries. However, a hypocaust was not found in any of the rooms and the east room is not covered with a pierced dome, both being the standard architectural indicators of a bath space. Entry to the square room of the southern corner is from the courtyard. This room is covered with a cross vault of brick.

Mosque:

The building's small mosque is located in the upper storey above the entry gate portal. It is reached by a stone staircase of 11 steps. The mosque is decorated very sparsely, and comprises a stone mihrab with a niche decoration of stalactites and other geometrical decorative elements. The roof, ruined before the restoration was complete, was covered by a star cross-vault. The mihrab, whose two borders were significantly damaged, has been restored. The outermost border displays a guilloche motif in low relief, and the outer border has a wider braided motif.

Covered section:

The southern part of the han comprises a covered section (22 x 28m) which was used

in the winter. This is a large and high space, and resembles a cathedral nave.

There are 5 vaults and a dome in the covered area.

Access to the covered section of the han is through a magnificent crown door in the middle of the east façade. It is composed of an alternating use of two differently-colored stones. The crown door projects forward slightly from the main wall. The crown door frames a pointed arch vault surrounded by one plain border and another with a half star motif. The inscription plaque, composed of two marble pieces, is surmounted by an arch and the sides are framed with recessed rectangular stones in the tympanum. The decorative braiding surrounding the inscription plaque is noteworthy.

The covered section is entered from the east onto a middle nave, which is flanked by two lines of piers supporting the side naves. The side naves continue to the back wall and are covered with lower pointed barrel vaults than those of the central nave. The vaults of the central nave are connected to each other by rib arches in the north-south direction. All the piers in the covered section are square. The section between the fourth and fifth piers is covered by a dome. Squinches comprising muqarnas are used as a transition element for the dome. A slit window is situated in each face of the squinches. The dome has been rebuilt during the recent restorations, but the outer pyramidal cone has not been restored. The han is lit by slit windows in the second, fourth and sixth naves in the north and south walls. There are four slit windows in the dome lantern of the middle nave and another one in the west wall of the middle nave.

The raised platforms were revealed during the excavations of 1996. The platform system of this han has a unique design. The section that begins in the middle of the central nave is designed as a flat corridor and the north-south sections up to the piers were designed as side platforms. The middle platform was designed with indentations opening around the corridors like a labyrinth, a layout which suggests they were built to be used by people, not animals.

The covered section is lit by slit holes instead of windows in the covered section. The lantern dome

of the covered section rests on squinches with stalactites. The section has

raised platforms for unloading and loading goods.

The excavations in 1996 revealed hexagonal brick floor pavers.

The covered section is reinforced with two support towers on the north, south and west sides. The south towers are hexagonal and the others are square. The north and south towers are opposite the support lines of the arches, while the west ones are not.

EXTERIOR

There are 2 corner towers and 11 towers on the exterior sides. The doors are bolted with a wooden bar which slid across it into the walls on either side.

A water well, in use until recently, was located on the caravan road that passes to the south of the han. Numerous fragments of ceramic tiles were found in the tumuli to the north of the han, and suggest that there were structures here before this han was built. Further excavations are needed to prove this assumption.

BUILDING MATERIALS

In addition to reuse spolia material, clean-cut and rubble stones were used for the construction of the walls. Bigger stones are used at the base. The walls are lined alternately with one thick and one thin stone. Mason marks can be seen on smooth-faced stones, especially on the stones used for the arches. The walls of the courtyard section were supported by seven towers, two each in the north and south walls, one in the east wall and one in the east corners. The tower in the middle of the south side and the tower in the south-east corner are hexagonal. The others are square.

DECORATION

The most significant decorative feature of the building is the use of the differently-colored stones, especially in the arches of the crown door and in the courtyard. The inner and outer doors are made of blue and white limestone courses which provide a decorative harmony of grace notes. This use of differently-colored interlaced stones is perhaps a reference to the famous north portal of the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya, added by Alaeddin Keykubad in 1220. Above these doors are inscription plaques. Ropework and sawtooth designs are the principal decorative element. The courtyard crown door on the south side is spectacular. The body of the portal extends from the wall and is composed of a wide, pointed arch. Two borders, one consisting of braiding and the other with half stars, surround the crown door opening. Two additional arches frame the crown door arch and continue to the ground level. The outer arch is decorated with a border of half stars similar to the outer border of the crown door.

Reuse material is an extensive construction and decorative element of this han. There are 189 pieces of spolia used in this han. The Zazadin Han has been celebrated by Byzantine scholars due to the extensive presence of Early and Middle Byzantine period travertine reuse (spolia) materials in its walls. The names Michael Arhangelos and Chorion Kapumaes can be seen in the Greek inscriptions on these reuse stones, which indicate that the material was taken from a nearby church. The use of spolia in this han is as extensive as the nearby han of Obruk. These two neighboring hans may possibly have taken the stones from the same nearby Christian church. Many of the stones are tombstones, often laid sideways.

Tile fragments were uncovered in the 1996 excavations, but it is not certain

if they were original to the structure.

DIMENSIONS

The total external area: 2,575m2

Area of covered section: 620m2

Area of courtyard: 1625m2

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

This han stood for many years in a semi-ruined state.

The han was featured in a documentary film on hans made in 1925, which depicted

its condition at the time. This han was left abandoned for many years, and

became a home for crows and vagrants. Renovations were undertaken in 1996, at

which time some serious alterations were made. The piers of the arcade were

reinforced with cement during this restoration.

The forward-looking mayor of the Selçuklu Township, Adem Esen, decided in 2005 to initiate a major renovation project for this han. The project was deemed important, not only to prevent its further deterioration, but also to restore it to its former glory. The $1.8 million restoration project began in December, 2007, and was inaugurated by Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan on April 25, 2008. A mere 210 days of breakneck activity by skilled artisans brought this han back to life, where it now serves as a community space for official ceremonies, conferences, concerts, receptions and other assorted public functions. The newly-renovated han was opened to the citizens of Konya with the organization of a joint wedding ceremony for 35 couples in its walls on May 25, 2008, a symbolic and inspirational setting for these young newlyweds to take their first steps together. The project was opened to the world on June 12, 2008, by an official dinner and concert by famed pianist Tuluyhan Uğurlu, held in conjunction with the 11th World Conference of Historical Cities which took place in Konya, attended by over 700 participants.

During the renovation of 2007, the previous cement applications were removed, the roof of the covered section was completed, the interior of the skylight dome was reinforced and its exterior was covered with a pyramidal cone of sheet metal. Regrettably, aesthetic attention was not paid to this work and the excavations and restorations were unfortunately carried out with little scientific approach. These uncontrolled restoration procedures caused much damage to the original building fabric. The worse result was the removal of the spolia material for no justifiable reason. These historic stones were removed and replaced with new stones. The walls were cleaned by sand-blasting which erased the decorative elements. The location of the removed spolia materials are today unknown a historic treachery of the highest order.

However, this renovation is a beautiful gift to the Turkish people, who will now make pilgrimage trips to Konya not only to see the tomb of Mevlana, but also to visit this important cultural legacy landmark. Konya, with its newly-restored houses and churches in Sille, this han and the others in the nearby region, Mevlana's tomb and the spectacular Seljuk-era Ince, Sahip Ata, Karatay and Sircali medreses, is now certainly one of the most important cultural destinations in all of Turkey, and a true crossroads of civilizations and cultures in the heart of Anatolia. Its impressive size, long and low profile, striking bicolor portals, intact inscription plaques and extensive spolia decoration make this an unforgettable han to visit. It will literally take your breath away in awe at the architectural legacy of the Seljuks.

The han was closed in September, 2017 due to additional restoration work, but reopened for visits in August, 2019.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC

REFERENCES

Altun, Ara. An Outline of Turkish Architecture in the Middle Ages, 1990, p. 200.

Baş, Ali. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Konya Kervansarayları. Çekül Sanatsal Mozaik, vol. 3/33, 1998, pp. 60- 69.

Baş, Ali. Yeni Buluntular Işığında Zazadın Hanının Değerlendirilmesi. I. Uluslar Arası Selçuklu Kültür ve Medeniyeti Kongresi- Bildiriler I (11-13 Ekim 2000). Konya: Selçuk Üniv. Selçuk Araştırmaları Merkezi Yayını, 2001, pp. 101-111.

Bayrak, M. O. Türkiye Tarihi yerler kılavuzu, 1994, p. 458.

Bektaş, Cengiz. Selçuklu kervansarayları, korunmaları ve kullanılmaları uzerine bir öneri = A proposal regarding the Seljuk caravanserais, their protection and use, 1999, pp. 90-93.

Belke & Restle, Galatien und Lykaonien,1984, p. 220.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, pp. 492-499.

Carver & Ramsaye. "Grass: A Nation's Battle for Life" [Film], 1925.

Demir, Ataman. "Anadolu Selçuklu Hanları, Zazadin Han-Sadeddin Köpek Hanı", İlgi, 44 (1986), pp.26-31.

Eravşar, O. Spolia in Seljuk Buildings. SOMA 2014: Proceedings of the 18th Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology. Wroclaw, 2014, pp. 167-182.

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 353-365.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961, pp. 102-107, no. 28; vol. 3, pp. 147-148.

Ertuğ, Ahmet. The Seljuks: A Journey through Anatolian Architecture, 1991, p. 79.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 519.

Hillenbrand, R. Islamic Architecture: Form, function and meaning, 1994, fig. 6.48, p. 552.

İbni Bibi. El Evamirü'l-Ala'iye, Fi'l-Umuri'l-Alai'iye (Selçuk Name), trans. Mürsel Öztürk, 1996, vol. 1 p. 361, 438; v.2, p. 28, 32

Karpuz, H. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, vol. 2, pp. 86-87.

Konyalı İ. H., Abideler ve Kitabeleri ile Konya Tarihi, 1964, p. 1055-1057.

Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Konya ve ilçelerindeki Selçuklu Eserleri, 2005, pp. 81-82 (excellent pre-restoration photos)

Önge M. "Zazadin Han" in Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı, 2007, pp. 194-209 (includes bibliography); pp. 466-467, p. 519..

Önge, Mustafa. "Caravanserais as Symbols of Power in Seljuk Anatolia. In Jonathan Osmond and Ausma Cimdina (eds.) Power and Culture: Identity, Ideology, Representation. Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2007. pp. 49-69.

Özergin, M. Kemal. Anadoluda Selçuklu Kervansarayları, Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 160, p. 102.

Rice, Tamara Talbot. The Seljuks in Asia Minor, 1961, p. 205.

Simon de Saint Quentin. Histoire des Tartares, edited by Jean Richard, Paris, 1965.

Yildiz, Sara Nur. The Rise and fall of a tyrant in Seljuk Anatolia: Sad al-Din Köpeks reign of terror, 1237-38. In: Firuza Abdullaeva, Robert Hillenbrand and A.C.S. Peacock (eds.) Ferdowsi, The Mongols and Iranian History. London, 2014.

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 358; photo I. Dıvarcı

|

|

|

|

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

|

Please click below for photos of the han after its restoration in 2007-2008:

The following photos show the han during the renovation, in July, 2007:

The following photos show the han before its restoration in 2008:

|

Courtyard looking towards the covered section

|

detail, western side of the courtyard |

|

Squinch brickwork in chamber at southeast corner |

Stairs leading to the mosque |

|

Stairs leading to the roof terrace |

courtyard, northeast |

|

Sunken area for stabling animals on the southern side of courtyard |

Stabling area on the southern side courtyard

|

|

courtyard arcades, northern side of courtyard

|

courtyard arcades, northeastern side of courtyard

|

|

Front wall showing spolia stones in situ

|

examples of spolia stones

|

|

Rear wall showing spolia stones in situ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overview of the Zazadin Han

|

|

The Konya-Aksaray road near the Zazadin Han, unchanged since the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Crusaders passed here |

***

The following excerpt from Yes, I would love another Glass of Tea, a series of essays on Turkey published in 2010, shares an anecdote about the adventures of researching hans that the present author encountered in the 1970-80s, in the days before GPS, ready transport, digital photography and cell phones, and when most of these hans were not easily accessible.

Nothing quite prepared me for some of the dramatic and unorthodox entries I have experienced in order to get inside of hans during my research trips. One of the oddest was at the Zazadin Han outside of Konya. The han is in a fairly deserted area, in the midst of sown fields... I walked across a deserted field of rubble and thistles to reach its impressive main portal. Of course, it was padlocked. My heart sank as heavy as that cursed lock: how unfair to be frustrated after such a hot trek across that prickly field, which had torn my hem and bloodied my ankles! Except for those cows and the buzzing flies around my head, there was no sign of life or any hope of helping hands. The walls of the han were extremely high, so I knew I would not be able to achieve one of my Mt. Everest repelling expeditions. Frustrated, but still determined to get the best out of the visit that I could, I resigned myself to walking around the perimeter of this vast han to observe its fine outer walls, which were decorated with numerous carved stones taken from Byzantine churches. As I stood there sketching the design of one of these recycled blocks, I sensed the presence of someone by my side. Silently and seemingly out of nowhere had appeared next to me a strange-looking, dark-haired man with wild black eyes, dressed in grimy khaki fatigues, combat boots and carrying a long, black 12-gauge hunting rifle. I took a deep breath, and wondered how I was going to extricate myself from this situation with my life intact. He stared at me, glanced over at my notebook and started to speak, his ebony eyes flashing in the bright sun. Although I had a bit of trouble deciphering his garbled speech and that dense accent of Konya, I came to understand that he was a nomad living off the land, and that he had come here to shoot birds. As he explained it, the han was full of many kinds of plump game birds that he could easily bag. Come, I will show you! he stated, and although I was still more than uneasy about it, I followed him. Would I ever have followed an incoherent, wild-eyed itinerant man with a shotgun in a deserted field in America? Not on your life; but this was Turkey, and somehow I trusted that this was not going to end tragically, but, on the contrary, very, very well. We came around again to the front of the han, and, without a moments hesitation, he lifted his shotgun and took aim. After a flash of light and a roar, the padlock was history. Swinging by its singed metal bits on the frame of the door, it was no longer an impediment to my entry or to his bagging dinner. And so, in this rather unconventional way, I gained entry to one of the largest and most impressive hans in Turkey, which was indeed filled with hundreds of game birds flittering in the eaves of the deserted covered section. When my hunter started after them, I turned to study and sketch the han, wondering if I would ever have such an eventful entry again .but of course, this being Turkey, I did.

©2001-2025, Katharine Branning; All Rights Reserved.