The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

ALTINAPA HAN

Considered by many to be the oldest han built by the Seljuks, the Altinapa Han now lies submerged under the waters of a dam near Konya.

|

|

photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

|

|

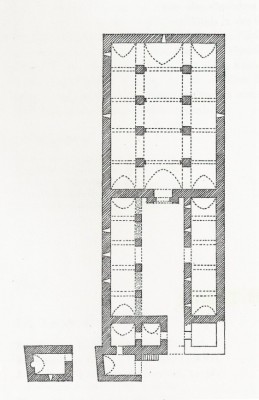

plan drawn by Erdmann |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 188; photo I. Dıvarcı |

DISTRICT

42 KONYA

LOCATION

37.880553, 32.302911

The Altinapa Han is located on the Konya-Beyşehir

road, about 21 km outside of Konya, right before the small bridge over the

Altinapa Dam. Be aware that you will not generally be able to see it, for it

is now covered over by the waters of the Altinapa Dam, built in 1954.

Immediately before crossing the bridge, there is a side road to the north (turn

right) that goes down closer to the shore of the dam lake. In periods of drought

when the lake waters are low (as is often the case in the summer), this han may

be viewed from the road.

This caravan route continues on to Antalya. The Dibi Delik Han (Hoca Cihan Han) is also on the same stretch of road, and the Kiziloren Kandemir Han lies a bit further west of the Altınapa Han on the way to Beyşehir. This road lead to Derbent and Doğanhisar, and was used by the Seljuks as frequently as the current one linking Konya to Beyşehir, known as Gorgorum in the Seljuk era.

The han sits on the southern slope of a small hill, and the Başara River once flowed directly in front of it.

NAMES

The han is not mentioned in any of the accounts of travelers exploring the region. Pace was the first person to have made a rendering of the han, detailing its architectural plan. He associated the name of the han with the number of arches in the closed section and states that "Altı Napa" is derived from the term meaning "Six-arched Han" (altı meaning six in Turkish). However, as there are five arches in the closed section, it appears that this name is a fabrication. Erdmann interprets the name of the han as "Altın Baba" (Golden Father). However, today the general consensus is that the name is a derivation of the name of Altunapa Şemsettin, an important Seljuk emir, and considered the patron of the han, although this han is not recorded in the deed of his charitable foundation. Kiepert marked it as "Seldjuk Han" on his map.

INSCRIPTION

The inscription plaque over the main door has been lost, but the han is dated in association with the date of the patron's commissioning of the Iplikci Mosque in Konya (1201-2). The foundation deed document also speaks of the Iplikci Medrese (home base for Mevlana).

Pace, traveling in 1923-26, saw the inscription over the covered section door and indicated that a sizable part of the inscription was illegible. Riefstahl, who visited the area after Pace in 1930, did not see the inscription, so it must have disappeared in 1929. Erdmann mentioned the existence of a second inscription, dated 1229 AH /1812 AD, but it too has been lost.

This is considered to be the earliest Seljuk han in Turkey, and is a part of the dense chain of hans between Konya and Beyşehir (Kizilören Kandemir, Kuruçeşme, and the now lost Yunuslar Hans), all of approximately the same date. Since it can no longer be viewed or studied, one must rely on past descriptions, notably by Erdmann who documented it in 1953.

DATE

1201-1202

PATRON

Construction of this han is believed to have been commissioned by the Seljuk statesman Şemsettin Altinapa. Şemsettin Altinapa (variant spelling is Altun-Aba) was an important vizier serving under Alaeddin Keykubad.

Despite the loss of the inscription plaques for the han, there is a record which can help identify the patron. One of the few remaining Seljuk period foundation charters belongs to the Altinapa Han, and it mentions the exact name of the han. This deed of the charitable foundation of Altunapa Şemsettin, dated 598 AH /1202 AD, concerns the Konya Iplikci Medrese which he built. This foundation document is one of the oldest documents pertaining to Konya, and fives insight into the topography of the area and the neighborhoods of Konya. The foundation deed of the Iplikci Mosque reveals that a han and the shops of the villages of Saraycık, Gündoğdu, Ladik, Gedil and Arkıt are property of the foundation of the Iplikci Medrese. The han specified in the deed is located between Konya and Gorgorum, and which had been donated by a certain merchant Haji Bahtiyar bin Abdullah of Tabriz. Today, the known hans on this road are the Altınapa, Kiziloren Kandemir, Kuruçeşme and Yunuslar hans, this latter han having been unfortunately totally demolished. Erdmann believes thus that this could very well be the han built by Haji Bahtiyar, son of Abdullah, the merchant from Tabriz, who is recorded in the Konya Iplikci Medrese deed. Even though the Tabriz merchant may have sponsored the han, for reasons unclear it has become associated with the name of Altinapa over the years. The Iplikci vakif mentions the amount of wood to be provided for heating the han and the amounts of linseed oil needing for lighting the lamps, the cost of which were to be provided from the profits earned by a shop in the Eski Bazar in Konya. The han may have been completed several years before the writing of the vakif document.

The famous Iplikci Medrese served as the teaching headquarters of the Bahaeddin Veled, the renowned Islamic scholar and father of Mevlana. After the death of his father, Mevlana continued to teach here, and it became the home of Seljuk Sufism. The historian Eflaki relates this incident concerning the headstrong father of Mevlana. When Bahaeddin Veled arrived in Konya in 1228 upon the invitation of the Sultan Alaeddin Keykubad, the sultan invited him to settle in the royal palace. Bahaeddin rebuked him by saying: "The place of imams is in the medrese. Sheikhs go to dervish lodges, beys go to palaces, merchants go to hans, and the poor to tombs" He then chose the Iplikci Medrese as the place where he would teach.

The vizier Shams al-Din Altinapa began his career as a military commander for Sultan Kiliç Arslan II and his son Rukneddin Suleyman. He continued to serve under Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev I, and then his son, Alaeddin Keykubad. His long career ended under the son of Alaeddin Keykubad, Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev II. He served as both çaşnigir (food taster of the sultan, a highly-esteemed position) and sipesalar (military commander, distinguishing himself at the battles of Yassicimen and Ahlat. The historian Ibni-Bibi relates that he was at the battle of Kahta, and afterwards went to Damascus to broker the wedding agreement between the Ayyubid court and the Seljuks for the hand of Gaziye Hatun, the daughter of Ebubekir el-Adil, the Ayyubid ruler. He escorted the bride to Malatya where the wedding of this second wife with Alaeddin Keykubad took place in 1227. Later, Altinapa served as the atabeg (imperial guardian) of Alaeddin Keykubads first son, Giyaseddin Keyhusrev II. After the unfortunate murder of sultan Alaeddin Keykubad in 1237, the court historian Ibn Bibi provides a detailed account of the enthronement ceremony of Alaeddin Keykubads son Giyaseddin Keyhusrev II in the palace in Kayseri. In accordance with protocol, the Prince was lifted onto the throne by the generals, with his atabeg Altinapa holding his right arm and his lala (tutor) Cemaleddin Farrukh holding his left one. It is even reported by Ibn Bibi that after kissing the hand of the newly-installed sultan, Altinapa ruffled the fifteen year old Giyaseddins hair in a display of avuncular affection. However, this affection for the teenage sultan would lead to his downfall. Later on, Altinapa noticed the disturbing influence that the malevolent vizir Sadettin Kopek had on the young sultan. He encouraged his insecurities, pushed him to binge-drinking episodes, and advised him to make risky political decisions, all the while seeking to take his place on the throne. Altinapa tried to get support from the other viziers against Kopek, but the villainous vizier responded by making up falsehoods about him and convincing the sultan Giyaseddin Keyhusrev to have his atabeg Altinapa eliminated. While the court was in session in Antalya, Altinapa was dragged by his white beard as per Ibn Bibi, from the meeting held at the royal palace where he was signing official documents. He was thentaken out to be murdered in an ignoble fashion in the countryside by one of the Sultans imperial guards. It is estimated that he was 60-70 years old at his death. His dishonorable assassination began the downfall of the two-year long power spree of the tyrannical Saadettin Kopek (1237-38).

The vizier Altinapa was responsible for the construction of the Altinapa Mosque and Medrese in Konya where Mevlana preached, as well as the Argit Han on he Konya-Akşehir Road, now in ruins. Despite the fact that he was assassinated and his beautiful han submerged in a lake, the memory of this noble vizier lives on as one of the finest statesmen of the Seljuk era, along with Kemaleddin Kamyar and Mübarizuddin Çavli.

REIGN OF

Rukneddin Süleyman Shah II

BUILDING

TYPE

Covered open courtyard (COC)

Covered section and courtyard of the same width

Covered section with a central aisle and 1 aisle on each side running

perpendicular to the back wall

5 bays of vaults parallel to the back wall

DESCRIPTION

Courtyard:

The courtyard section has completely collapsed and is in ruins. Although the crown door of the courtyard no longer exists, foundation traces show that is was not set directly in the axis of the courtyard, but slightly to the north.

Several rooms covered with pointed barrel vault on both sides of the entrance can be discerned in old photographs and the plan recorded prior to the collapse of the courtyard. Immediately to the left upon entering, there are two rooms which were probably an office for the manager of the han and a treasury.

An arcade with four piers, connected to each other by five pointed arches, originally stood on the southern side of the courtyard. The arcade was covered with a barrel vault running in the north-south direction.

On the northern side, there was a barrel-vaulted room with a wide central entrance and four windows opening to the courtyard. The pointed barrel vault was supported by pointed arches placed at regular intervals. Only the cells on the southern side had window slits.

Covered section:

The covered section has three naves, each connected by five pointed arches. The main arches are also supported by pointed connecting arches built between the walls. High arches spring from piers that are nearly one meter in height. The first three piers facing the central nave are reuse columns, while the last two piers at the rear are square. The closed section was lit by four windows, one positioned at the center of the rear west wall in line with the central nave, two located in mid-axis of the third arch of the side walls, and one placed on fifth rear arch of the southern facade.

The crown door of the covered section preserves its main characteristics, but has deteriorated over time. The photographs taken by Erdmann in 1967 show that the door was still in good condition. Reuse spolia material has been placed on the door, as well on the interior. Spolia can be observed in various parts of the han, such as on the outer façade, the portal, the piers which have spolia capitals and bases, and the inner segments of the arches. The window slits have Byzantine frames. The spolia here is different than the other spolia seen in the Konya region, and may have come from a different source. A stepped stone arch sits above reused stucco elements. A wide, pointed arch provides an opening above the door, and rests on reuse materials. An inscription niche with a pointed arch is located above the arch of the crown door, but is blank. No decoration or ornamental elements can be seen on the surface of the crown door.

Mosque: Historic photographs taken by Erdmann in 1967 reveal that there was a two-storey structure to the left (east) of the entrance, approached by 3 steps, but it has now disappeared. This structure was believed to have served as a mosque, due to the presence of a set of stairs on the eastern section of this space. This type of mosque was also seen in the nearby Kızılören Kandemir Han. The stairs at the eastern side of the han were used to reach the upper floor of the two-storeyed mosque. The lower floor of the mosque was designed in the shape of an iwan which opens in the direction of the main entry crown door. A section with a pointed vault, located towards the crown door, most likely served as a fountain iwan, as is seen in the Alara Han. The mosque, covered with a pointed barrel-vault running in the north-south direction, included a mihrab (prayer niche) located in the center of the southern wall. Erdmann mentions the existence of reuse columns from the Byzantine period on both sides of the mosque entrance.

BUILDING MATERIALS

The north, south and east sides of the han were made with finely-cut stone blocks. The west side incorporated rubble stone into the stone courses. While the walls of the covered section were carefully built using short and long sequences of dressed masonry, the courtyard walls were built more imprecisely using rougher cut stone blocks.

A considerable amount of reuse material has been employed in the construction of the han. Spolia stone is seen in the arches and columns of the covered section. Erdmann noted that there were many Byzantine reuse stones from Christian churches in this han, as seen in the nearby hans of Obruk and Zazadin. The majority of this spolia materials consists of rectangular cut-stone blocks, some of which are half-columns. Most of these columns were placed on the pier bases facing the middle nave of the covered section. The two columns located on each side of the mosque door, carved with two shallow grooves, are also reuse material.

DIMENSIONS

This is not a particularly large han:

Total external area: approximately 770m2

Covered section area: 330m2

Courtyard area: 400m2

STATE

OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

Erdmann stated that excavations were being carried out when he examined the han. Other excavations were carried out in 1998 when the han became exposed due to drought.

This han was covered over by water in 1954 by the creation of the Altinapa Dam. Although now lying beneath the waters of the lake created by the dam, it may be viewed from a distance the waters of the lake are low during the summer months. It rises on a little bluff in the middle of the lake and can be seen from the side approach road. Due to a serious drop in the level of the dam waters it became completely visible on December 6, 2017, to the delight of researchers and the curious public as well.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Akok, Mahmut. Konyada Üç Tarihi ve Mimari Eser: Altınapa Kervansarayı, Hasbey Darülhuffazı ve Selim II. İmareti , Türk Arkeoloji Dergisi, XX / 1, 1973, pp. 536.

Baş, A. Konya-Hatunsaray-Seydişehir Kervanyolu Uzerine Düşünceler. V. Milli Selcuklu Kultur ve Medeniyet Seminenri Bildirleri. Konya, 1996, pp. 141-168.

Baykara, Tuncer. Türkiye Selçuklular Devrinde Konya. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 1985.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 2, p. 343.

Demir, Ataman."Anadolu Selçuklu Hanları. Altınapa Han", İlgi, 61 (1990), pp. 24-27.

Doğan, N. Ş. Konyadan Antalya-Alanyaya Uzanan Kervan Yollari Hakkinda Bazi Görüşler. 4. Alanya Tarih ve Kültür Semineri, 1994, pp. 381-386.

Duran, Remzi. Altinapa Hanı, Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara Kültür Bakanlığı, 2007, pp.76-87 (includes bibliography).

Eflaki. Ahmet Eflaki. Ariflerin Menkibeleri (Manakib ul Arifin) [Legends from the Wise Men]. Istanbul, 1964.

Eravşar, O. Spolia in Seljuk Buildings. in SOMA 2014: Proceedings of the 18th Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology. Wroclaw, 2014, pp. 167-182.

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 184-188.

Erdmann, Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961, no. 1, pp. 29-32 (numerous photos).

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 480.

Ibni Bibi. El Evamirü'l-Ala'iye, Fi'l-Umuri'l-Alai'iye (Selçuk Name), trans. Mürsel Öztürk, 1996.

Karpuz, Haşim. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, vol. 2, p. 81.

Kiepert, R. Karte von Kleinasien, in 24 Blatt bearbeitet, 1902-1916.

Konyalı, İ. H. Abideler ve Kitabeleri ile Konya Tarihi, Istanbul, 1964.

Kuban, D. Selçuklu Cağinda Anadolu Sanati, 2002, p. 238.

Özergin, M. Kemal. Anadoluda Selçuklu Kervansarayları, Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, pp. 145, n. 7.

Pace, B. Richerche nella regione di Conia, Adalia e Scalanova. Annuario della R. Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiane in Oriente, 1923-1926, 1926, pp. 390-392.

Turan, O. Semseddin Altun-aba Vafiyesi ve Hayati. Belleten 1947, vol. 11, pp. 197-235.

Turan, O. Selçuklu Kervansaraylar, Belleten vol X:9, 1946, pp. 478.

Uysal, A. O. Konya-Eğirdir Güzerhahinda Bazi Kervansaralar. III. Milli Selçuklu Kültür ve Medeniyeti Semineri Bildirilen. Konya, 1994, pp. 71-83.

|

Photo by Erdmann (#2) |

|

Photo by Erdmann (#4) |

Photo by Erdmann (#3) |

***

The following excerpt from Yes, I would love another Glass of Tea, a series of essays on Turkey published in 2010, shares an anecdote about the difficulty of researching hans that the present author encountered in the 1970s.

To find a han, there were often aggravating challenges: mismarked maps, non-existent roads, conflicting information in texts, and no signs, but the most frustrating was the fact that few local Turks were able to help me when I asked them for directions. The combination of my poor Turkish, foreign accent and differences in local dialects often made asking for directions a challenge. Another complication is that a Turk is reluctant to admit to you that he does not know what you are talking about or that he doesnt know where it is. I have learned that Turks hold honor over truth, and sometimes have difficulty distinguishing between theory, the desire to be helpful and practice. They will tell you that something exists (or is even just in the planning stages) just to make you happy. Taxi drivers do not always know where they are going either, but seldom admit it, often driving around in circles. They will also refuse to show you something they think you should not see, much like the waiters in restaurants who will not allow you to eat what you want if they do not think it is in your best interest. When the locals do know that old pile of rocks I am referring to, they scratch their head in disbelief when this foreign woman is asking directions to see it, and say, But why in the world do you want to see such an old thing?

Being a solo pioneer may have led me on some complicated, round-about trails to find a han, but in doing so, I had the opportunity to spend time chatting with people and learning local lore that I would not have learned had I arrived directly in front of my destination. So my golden rule has become to be patient: not to rush, not to get upset that you cannot get the immediate answer to your questions, to accept that the answer given may be embroidered, and to use this moment to pursue some interesting interchange. Ask directions from five people and take the majority view, say a prayer that after traveling 500 miles to a hot and arid place, and lo, and behold, eventually, you should be able to find your han. For, in the end, a Turk will never say I dont know and leave you stranded: of that you can be assured. A Turk will never say no to a request for information, and will spend a whole day with you trying to help you find your treasure, for a Turk is always an optimist.

An example of this optimism was seen in my search for the Altinapa Han. I had read in many texts that it existed, and I had seen old photos of it in dusty books. Yet it proved impossible to find it on the road outside of Konya at the spot where it should have been located. I stopped my car to ask directions at a roadside tea garden, and a typical chaotic alla turca scene ensued, with 6 Turks and 6 different semi-answers. First, I approached a 50 year-old Turk, thinking he would have some knowledgeable idea about the area in which he lived. He paused for a moment and replied, Well, yes, I have heard of it; yes, well, lets think, well, thats right, there is a han around here somewhere .. He did not seem to know, but in a typical positive Turkish fashion, did not wish to appear unhelpful and continued to talk around an answer as politely as possible. A second Turk showed up, entered into the conversation and piped up, I think I can help! I am sure my friends will know! He grabbed me and took me around to a charming set-up of picnic tables overlooking the lake created by the Altinapa Dam. Sitting there were three Turks, enjoying the view over the water, smoking cigarettes and drinking tea. The third Turk put down his tea and pointed across the lake. See that grove of poplar trees over there? Well, it is behind them. You can find a road that will go over there. His friend, the fourth Turk, interjected: Oh, no, abi (big brother), its not there at all, that han has completely fallen down and no longer exists! The tone started to rise. Now piped up the fifth Turk: Oh, my brothers! You have got it all wrong; it is lying at the bottom of the lake! A heated discussion with much hand-waving, yelling, pushing and poking ensued, with another round of tea ordered to bring counsel. The sixth Turk, who appeared to be the umpire in the situation, concluded the discussion by saying: Well, wherever it is, Im sure it is just fine. Now, dont you worry about it, my Lady Visitor, you will find lots more old hans in this area if you want to see one, and after all, what was so special about that particular one? Ill help you find one you will like just as well! In reality, the fifth Turk had it right. One of the tragic victims of Turkeys vigorous dam construction projects was the Altinapa Han, which was flooded over when the dam was built in 1954.

©2001-2025, Katharine Branning; All Rights Reserved.