The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

TUZHISAR KAYSERI SULTAN HAN

This outstanding han, the second largest in Turkey, is another enduring legacy of the Sultan Alaeddin Keykubad. One of the most luxurious hans ever built, the Kayseri Tuzhisar Sultan Han was the five-star "Hilton" of its day. Its kiosk mosque in the courtyard, decorated with fierce dragons, is the finest example known.

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p. 475 |

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p. 473 |

|

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

axonometric drawing by A. Gabriel (the camels, drawn for scale, are a bit too small) |

|

Karpuz, Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri (2008) v.1, p. 474 |

Bilici, vol. 2, p. 255 |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

sculpted fan in portal entryway |

|

arch on western side of main portal |

|

polygon carving on side panels of portal |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 425; photo I. Dıvarcı |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

elaborate carved ribbon of dragons on kiosk mosque arches |

Eravşar, 2017. p. 427; photo I. Dıvarcı |

photo by John Ingham, 1961 |

|

Talisman Gate, Baghdad (1222), photo by F. Sarre and Ernst Herzfeld, 1911 |

Steps leading to roof terrace in the northwest corner of the courtyard |

plan drawn by Erdmann

lion head waterspout in courtyard |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

Bilici, vol. 2, p. 260 |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

axonometric drawing by Mahmut Akok (the horsemen, drawn for scale, are a bit too large) |

DISTRICT

38 KAYSERI

LOCATION

38.972758, 35.895262

This han is located 45 km northeast of Kayseri on the Sivas Road in the village of Tuzhisar in the Bunyan district of Kayseri. The han was formerly located on the older Sivas road which was the major route linking Konya, Kayseri and Sivas to the east (Iraq and Iran). However, but this road has now been replaced by a larger modern highway which has covered over the original caravan route. The han is visible from the road. The road is reported to have been used by the Romans, and probably before that in the Assyrian Trade Colonies and Hittite periods, in view of the ancient annual international trade fair of the Yabun Pazari, which was located in nearby Kayseri (Pazarören).

NAMES

Tuzhisar Sultan Han

Palaz or Palas Sultan Han

Kayseri-Bunyan Sultan Han

Büyük Kervansarayı

The name of Tuzhisar ("Salt Castle") was probably given to the han after the nearby Tuzla Lake and the remains of an old castle in the region. The name of Sultan Han must have been attributed due to its probable commission by the Seljuk Sultan Alaeddin Keykubad.

Although historical texts speak of the many hans along this road, the actual name of this han has never been indicated in any source. However, information about the han is found in Seljuk-era sources, notably as concerns the important expedition of the Mamluk commander Baybars who stayed in this han. Baybars invaded Anatolia from Syria in 1277 to try to put an end to the Mongol control of the region. He defeated the Mongol army at the famous Battle of Elbistan (April 15, 1277) and one month later entered the city of Kayseri and had himself crowned emperor at the Devlethane Palace according to the old Seljuk rituals. During his journey he was accompanied by Qadi Muhyiddin Abduzzahir, who kept a diary of the military expedition. According to his telling of the events, the Mamluk army defeated the Mongols during an expedition to Akça Derbent and afterwards marched on to Kayseri via Elbistan. The army stayed in Kayseri for one week and then left the city to give the impression that they were planning to attack the Mongol army. In reality, Baybars was fearing a Mongol counterattack and decided to return to Egypt. He was far from his bases and supply lines and felt vulnerable. Baybars was also angered at the duplicity of the powerful Seljuk Vizier Muineddin Pervane of Tokat who was playing both sides as a double agent. Baybars told Pervane that he was leaving for Sivas to mislead him and the Mongols as to his true destination. His army took the route northeast towards Sivas and stopped here at the Tuzhisar Sultan Han. Qadi Muhyiddin Abduzzahir called the Tuzhisar Han the "Alaeddin Keykubad Han" in his journal. He described the han as having a rich foundation and that sheep were raised in the vicinity to feed the passengers who visited the han. After their stay at the Tuzhisar Sultan Han, the army changed direction once again to confuse the Mongols and headed south towards Elbistan and stopped at the Karatay Han. The Mongol commander Abaqa took advantage of the retreat of the Mamluk Baybars and reasserted his authority over Anatolia once again. Abaqa, angered by his defeat at the Battle of Elbistan where he felt he had been betrayed by the Seljuks and especially by the Vizier Muineddin Pervane ordered the destruction of the city of Kayseri, where large numbers of its citizens were killed. He then ordered the execution of Pervane. The historian Aqsarayi also speaks of this event, stating that Baybars fought a battle with the Seljuks near this han during his 1277 campaign in Anatolia against the Mongols.

Other visitors left accounts of this han, for a han this big was hard to miss! One of the most curious is the text written by the 14th century Florentine broker Francesco Pegolotti (d. after 1347). This text is quite unusual, as it is a type of Baedekers guide destined to be used by merchants to the East. In this intriguing medieval business guide book, entitled Pratica della Mercatura (The Practice of Commerce), Pegolotti lists such handy items as the various tax duties to be paid in each city, currency exchange values, business etiquette tips, and a vocabulary list. This text is the also the first time the word caravansaray is used to denote these buildings, which the Turks called hans. Furthermore, this text is of great interest because Pegolotti lists all the toll stations along the route from the port of Ayas on the Cilician Mediterranean coast, up to Sivas, over to Erzincan and Erzurum and then on to Tabriz in Iran. Quite a feat, considering that he based his manual on the accounts of other traders who had used the Anatolian routes, since he himself never traveled to Anatolia! He specifically and clearly mentions the Sultan Han of Kayseri, calling in the Gavsera del Soldano. The han was described by many foreign travelers to the region in the 19th and early 20th centuries: Bruce (1820), Kinneir (1818), Mordtmann (who called it the "Sultan Han"), Cholet (1892), Tozer (1881, who called it the "Sultan-khane" but mistakenly believed it to have been built by the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV (r. 1623-40), de Jerphanion (1926, who drew its plan) and Gabriel (1931, who photographed it). The journal entry of Cholet gives us a lesson on why travel journals must be read with indulgence: "This han is believed to have been built by Sultan Souleiman. With the lack of common sense which so often characterizes oriental monarchs, rather than build, at regular intervals along the road, comfortable relays which would allow caravans to find each evening a comfortable spot to rest, this sultan only built one, but it is a veritable palace. This is one of the most beautiful specimens of Arab art."

DATE

1230-1234

The inscriptions over the main and courtyard doors are now illegible, so dating

is estimated by comparison with the Sultan Han Aksaray, which probably preceded

it.

The attributes of Alaeddin Keykubad were once legible on the inscription, and, as these names are mentioned on previous inscriptions dating to 1233-37, it can be assumed that the han was built during those years.

REIGN OF

Alaeddin Keykubad I (1220-37)

INSCRIPTION

There are two inscriptions, one over the main door and the other over the door to the covered section. Both are now illegible.

The inscription above the entrance of the covered section is intact, but the text is in a ruined state. It is barely legible, and only the last line survives. The inscription was written in naskh style calligraphy resembling the Kufic style. The name of "Burhan Emir El Mumin" was legible until recently on the inscription. Some early researchers had seen the inscription, notably Riefstahl, who read the parts that mentioned the epithets of Alaeddin Keykubad. The attributes of "Abul feth" and "Kasim emir muninin" definitely refer to this Sultan and were listed on the inscriptions of other buildings erected during his reign.

In addition to this inscription, there is another frieze under the lantern dome in the covered section of the han, written in naskh calligraphy. The phrase of "basmala" and "thanks to Allah" can be read in this inscription but the rest cannot be deciphered.

Lastly, the name of "Ameli Yadigar" is written on a block above the northwest corner tower of the courtyard, and could possibly denote the architect.

PATRON

Alaeddin Keykubad I (presumed in view of his intensive building

program in this region and his attributes once legible on the inscription). It

is known that this sultan had an intensive building program in this region.

The architect could have been the Ameli Yadigar mentioned on the courtyard tower, although there were probably many master builders working on this han in view of its size.

BUILDING TYPE

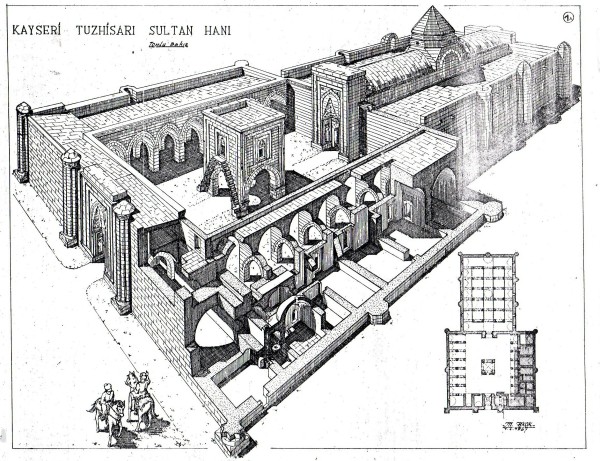

Covered section with an open courtyard (COC)

Covered section smaller than the courtyard

Covered section with 5 naves perpendicular to the rear wall

7 lines of support cross-vaults parallel to the rear wall

DESCRIPTION

The han is oriented north south, and the entrance faces the north. It consists of a covered section used for lodging and an open courtyard with service areas. The courtyard is larger than the covered section, and both entrances are on axis.

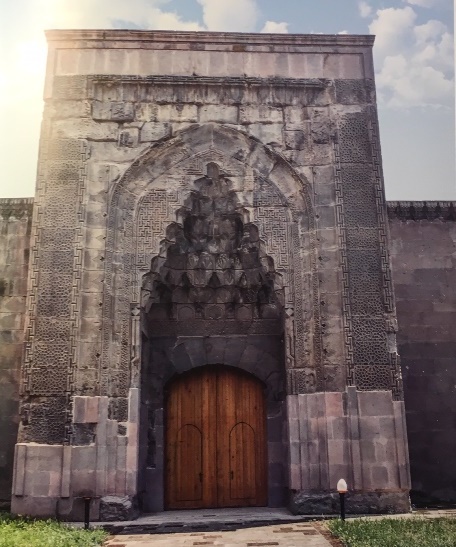

Crown door of the courtyard: The main door of the han projects slightly from the main wall. Support towers were placed on the corners at a later date and were designed integrally with the door. These rectangular buttresses are faced with semi-circular stones and create an effect of colossal power. Many of the original elements of this door were unfortunately compromised during the restoration. It originally comprised nine rows of muqarnas above a U-shaped arch surrounded by different borders. Some of the borders are incomplete but can be seen on old photographs. The wide range of carved decorative elements in the borders comprise T-shapes, 8-pointed stars, interwoven half stars with indented centers, meanders, half-squares, and geometric mesh patterns. Small, semi-cylindrical columns frame the door and help to support the arch. Their shafts are covered with a geometrical mesh pattern. The decoration of the capitals is no longer visible, but old photographs reveal that they were once decorated with vegetal, rumi, geometric and figural elements. Rosettes are placed under the prism elements of the muqarnas of the crown door. The center of each rosette is decorated with a different pattern, such as the Seal of Suleiman (aka Star of David) and pinwheels. The crown door arch was built using alternating stones of two different colors with grooved joints. There are niches on the interior faces of the entry portal, with three lines of muqarnas. A rosette is located in each corner of the arch. On the tympanum is a lively composition of deeply-engraved four-pointed stars.

The interior side of the crown door, facing the courtyard, is as elaborate as the front side: no expense was spared to render this han as attractive as possible for its users. Safety, comfort and splendor, all under one roof.

Entry iwan: This portal gives access to the courtyard after passing through a magnificent rectangular iwan facing south. Lift your eyes, dear visitor, and behold the star vault announcing the marvels to come in this han. This entrance iwan was created to dazzle visitors with its splendor, and is an absolute masterpiece of Seljuk decorative art. One can only imagine how impressed the caravan travelers must have been about the power of the Seljuk Empire when they entered this space after a long and tiring journey on the road.

Each side of the wide entry iwan is flanked by a series of vaulted rooms of varying sizes. To the east (left) is a small room covered with a barrel vault in the north-south direction which was most certainly a room for the guards. Next to it is a space in the shape of a small iwan. The exact purpose of this space in unknown, but it may have been a fountain. In the far eastern corner is a large rectangular room, set in the east-west direction and covered with a pointed vault. This room is accessed from the open arcade on the eastern side of the courtyard and may have been the quarters of the han keeper.

On the west (right side) is another room, divided in two parts by a central arch. It is accessed from the courtyard, not via the iwan. The layout is curious: the first section is covered with a vault running in the north-south direction, while the second is covered with a pointed vault in the east-west direction. Stone consoles were placed on the interior walls of this room, and their presence suggests that a wooden platform supported by wooden columns must have existed here. Perhaps this wooden platform served as a sleeping area for guards or administrators, or was used for storing valuable goods or perishable foodstuffs. Next to this unit is a room accessed via the courtyard (again perhaps for the han keeper or personnel). In the far western corner is a room which is entered from the bath suite (see below). This room is a bit of a mystery. It is lit by a window opening at the top of a specially-designed vault in the north-south direction. It is very dark here, and in view of its proximity to the water services of the bath suite of rooms, it is possible that this was a latrine or a private bathing space.

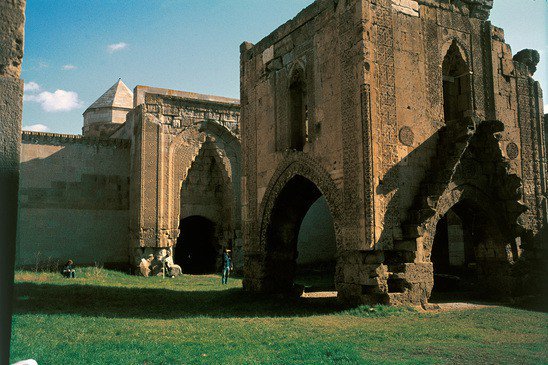

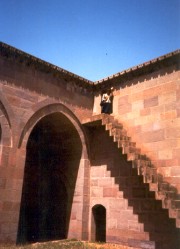

The entrance iwan opens onto a vast square courtyard. The courtyard is larger than the covered section, and both entrances are on axis. It is built on a slight incline from the south to the north to aid in drainage, as is the case in many Seljuk hans. Units of various sizes line both sides of this wide courtyard. A single flight of 18 stone steps at the southeast corner of the courtyard leads to the roof.

Kiosk mosque: Upon entering the courtyard, all eyes are drawn to the powerful giant dragon ribbon motive is seen above the arches of the south and west arches the kiosk mosque which stands in the middle of the courtyard, raised on four square piers joined by pointed arches. The surfaces of the piers are richly-decorated and provide a powerful sculptural effect and include octagons with central rosettes filled with different decorative ornamentation: stars, pinwheels and spirals. But it is those two abstractly-rendered dragon heads which meet and face each other, snarling with their jaws agape revealing sharp teeth, that capture the imagination of all and are some of the most powerful Seljuk sculptural motifs ever created.

The entrance to the mosque faces the main door of the courtyard. The mosque is square in plan, measuring 7.90m on each side. It is two storeys high, with a double corbelled staircase built flush into the northern side, leading up to the muezzins platform and the undecorated prayer room. The steps of the double stone staircase leading to the mosque are formed as a triangle formed by six lines of muqarnas, and have rosettes underneath the steps. The door of the mosque is surmounted by an 8-pointed star vault. The door opening is set inside the wall surface of the mosque and is surrounded by two borders with half-stars and medallions of 10-pointed stars. There are spiral decorations on the surface of the arch and linear decorations composed of rosettes at the corners, surmounted by five rows of muqarnas over a flat marble lintel. The lower stones are smooth-cut limestone and the upper stones are of granite with some marble pieces interspersed among them.

The interior prayer space is square, and covered by a barrel vault, and lit by two windows on the east and west sides. These windows are surrounded by two decorated borders (with stars, vegetal elements, rumi split-leaves and mesh elements) and surmounted by five lines of muqarnas. The mihrab is on the southern side and has four decorated borders with half stars and 10-sided pointed polygons, and surmounted by five rows of muqarnas. Another small niche is located inside the main mihrab niche, and has three rows of muqarnas, completed by an engraved braid decoration. An interior stairway inside the wall in the northwest corner once gave access to the roof of the mosque.

Eastern side (to the left upon entering): The eastern side of the courtyard is comprised of an open arcade of two rows of seven units covered with barrel vaults heading directly into the courtyard. There are six support lines connected to each other by two pointed arches borne on two piers in each section. This area probably served as both a loading area and stables, and was certainly heavily-used in the summer months.

Western side (to the right upon entering): The west wing has a complex layout, consisting of a double set of units: an open arcade of one row of seven vaults connected to the wall behind it by six piers with arches. Behind this wall is a row of closed rooms covered by barrel vaults.

Bath: The northernmost (closest to the han entry) vault on the west side gives access to a cluster of rooms which serve as the bath of the han. It is of irregular plan, comprising a suite of five interconnected rooms covered with domes and vaults. The bath is accessed by a low-arched doorway. The first room is the dressing room, which is covered with a pointed barrel vault and receives daylight via the slit window in the center of the vault. The second room frigidarim (cold) room, which is square and covered with a dome set on triangular pendentives. Three oculi on the dome base illuminate the space. Next is the tepidarium (warm) domed bathing area with basins, with a stone slab and a water tap. This room is followed on the west by two interconnected rooms comprising the caldarium (hot) sections. The fifth room is the room in the northwest corner, which was accessed from the caldarium. As stated above, this dark room was either the latrines or a private bathing room. The cistern of the bath house, heated from below, is rectangular in shape covered by a barrel vault. It was discovered, along with the furnace, during the restoration, and traces of pipes can be seen in some of the locations of the bath. The window on the southwest wall of the private bathing chamber connects to the water tank. On the exterior, the round-arched opening at the western corner of the southwest facade is the stokehole of the furnace for the bath behind it.

The other six rooms to the south of the bath (towards the covered section) were entered via the courtyard arcade and were used for lodging. The last two rooms are more secluded, with the one to the far south entered internally from the room next to it. In view of this, it is feasible that these two rooms were used for lodging of important guests such as Baybars and Alaeddin Keykubad, who must have visited this han often on his numerous trips between the two capital cities of Konya and Kayseri. The guards would have been in the front room protecting the internal entrance to the room in the corner. A similar situation is seen in the Karatay Han.

The exterior walls of the courtyard are braced by eight support towers, one half octagonal on the east and west sides, full octagons in the corners, on the north side, and on both sides of the protruding crown door. There are consoles made of large, smooth-cut stones above the support tower at the northwest corner, as well as a piece of an inscription belonging to one of the master builders. A projecting set of stars on the western side of the north wall gives access to the roof of the courtyard. Rainspouts direct the water collected on the roof to the exterior in various directions. Some of the waterspouts in the courtyard are in the shape of lions heads.

Covered section: Walk across the vast courtyard and enter the monumental crown door with a high arch which leads directly into the covered section. The entry crown door is offset to the east, and projects slightly from the main wall. The crown door displays alternating blocks of stones of two different colors, with the outer sections engraved in the form of descending lotus blossoms. It is framed by four borders, each with a different decoration. Elements include braids, T-shaped elements, 20-sided polygons, intersecting crosses and half-stars. The pointed arch of the door is surmounted by nine rows of muqarnas. The door is framed by pillars on each side with a decoration of knots, and capitals cut in the shape of a 24-sided cube. Each corner of the arch above the crown door includes a rosette with a mesh pattern, one of which has been damaged and the other destroyed. Each of the lateral sides of the portal has a niche topped with three rows of muqarnas and framed with a border of geometric elements. The form and decoration of this door is typical of the traditional Seljuk design, and closely resembles the crown door of the Karatay and Ağizkara Hans.

The large covered section is entirely covered in vaults and measures 42.10 long and 29.15m wide. It consists of one principal central nave, covered by a pointed vault in the north-south direction. It is 5.95m wide, and is higher than the other naves. There are two symmetrical lateral naves, each with seven cross-vaults in the east-west direction covered with pointed barrel vaults. The vaults at the junction point with the central nave connect to form a transept. They are carried by six lines of support vaults supported by 24 piers. The supporting arches, placed transversally at the level of the piers of the central nave, also support the central nave.

The area had a raised loading platform to separate the animals from the humans, functioning much like a haha wall in a garden. The animals remained in the space closest to the side walls, and the middle was reserved for the travelers and communal functions. These loading platforms are located in the section between the two piers of the outermost lateral naves on both sides of the middle nave.

The covered section is lit by slit windows on the east and west walls opening onto each horizontal cross-nave, except for the third one from the entrance. In addition, two slit windows in the south wall illuminate the central nave directly. Even more light enters the space from the lantern dome, which is located in the section between the third and fourth piers of the central nave. The lantern dome is surmounted by a cone on the exterior. Its oculus measures 6 m in width. The transition of the lantern dome is made by corner pendentives formed by muqarnas. Circular medallions with different geometric decorations can be seen on the surfaces of each pendentive. The area above the pendentives is decorated with a line of lotus blossoms on the lower section, a line of naskh calligraphy, and finally, a double line of muqarnas, all connected to the lantern dome. Under the muqarnas at the base of the dome is an inscription citing the first four verses of the al-Fatih sura of the Qur'an. There are slit windows above the dome drum in all four directions to provide light to the interior of the covered section. An unusual rumi (split-leaf) decoration in the shape of a shield is located on the east side of the arch carrying the lantern dome of the covered section. The reason for placing such a symbol at a place barely discernible by anyone remains a question.

EXTERIOR

The exterior walls of the covered section are reinforced by two round support towers on the east and west exterior walls, and one on the southern wall. In addition to these round towers, polygonal towers are located on the southeast and southwest corners. The round-arched opening at the western corner of the southwest facade is the stokehole of the furnace for the hammam behind it. The support towers are not set opposite the arch lines of the interior.

BUILDING MATERIALS

The building is built mostly of smooth-cut tufa stones. The walls are made of smooth-cut limestone, and blocks of white limestone and marble can be seen in some sections. There are lion-faced water spouts on the walls. Mason marks can be seen on some of the stones of the exterior walls.

DECORATION

All eyes were on this elaborately decorated han from well down the road. Seljuk architecture prides itself on its attention-grabbing main portals, and this one does not disappoint. This han displays some of the most elaborate decoration seen on any Seljuk building, notably on the crown doors and on the mosque. The decoration of the mosque shows expert stone carving, and is no doubt the work of many masters on the project. It comprises geometrical motives, meanders, polygons and rosettes is extremely precise and of fine workmanship. There is a magnificent Greek key decoration on the door to the covered section. Decorative elements include arabesques, crescents, dragons, trelliswork, swastikas, Syrian knots, meanders, arched bricks, lambrequins and rope work.

As mentioned above, the mosque arches are decorated with a stunning, stylized ribbon ending with confronting dragon's heads. The dragon is a symbol of wealth and bounty, and is frequently mentioned in astronomy and cosmology texts of the 13th century. A similar ribbon of dragons can be seen above the door of the Baghdad Talisman Gate (1222), destroyed in 1917 but known via excellent photographs taken by Sarre and Herzfeld, and its presence here shows indicates that this symbol had significance in Anatolia as well.

The lion-headed gargoyles on outer walls are striking examples of realistic, yet stylized, stone carving. Their purpose was to drain water down from the roof, but they are also set to frame the entrances of the most secure rooms of the han.

DIMENSIONS

Total area: 3900m2

Area of hall: 1290 m2

Area of courtyard: 2100m2

It is somewhat smaller that the Sultan Han Aksaray.

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

The han was well-restored in 1951, 1964 and 2009 and is in good

condition. It is now run as a cultural site by the Turkish government and can be

visited (guardian's offices are next door). The roof and waterproofing were left

unfinished in the 1964 renovation, and, as a result, the walls and the crown

doors became constantly damp, causing surface loss of the stones. The damaged

stones were replaced in the 2009 restoration. Unfortunately, electric wiring has

been laid in many sections of the han which has damaged some of the decoration,

and the lighting poles placed in the courtyard, as well as the hardscaping,

distract from the visual authenticity of the original aspect of the courtyard.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı Publications, 2007, pp. 460-461; 463.

Akok, Mahmut. Kayseride Tuzhisarı Sultanhanı, Köşk Medrese ve Alaca Mescit Diye Tanınan Üç Selçuklu Mimari Eserin Rölövesi, Türk Arkeoloji Dergisi, XVII/2, 1968, pp. 5-41.

Aqsarayi. Kerimuddin Mahmud-i Aksarayi. Selçuki Devletleri Tarihi, 1943, p. 137.

Aslanapa, Oktay, Anadolu'da İlk Türk Mimarisi, Başlangıcı ve Gelişmesi. Ankara: Atatürk Kültür Merkezi Yayını, 1991.

Bayburtluoğlu, Z. Anadoluda Selçuklu dönemi yapi sanatçilar. Ankara,1993, p. 146-147.

Bektaş, C. Selçuklu Kervansaraylari, Korumalari ve Kullanilmalari Üzerine Bir Öneri = A proposal regarding the Seljuk caravanserais, their protection and use, Istanbul, 1999, pp. 114-121.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 2, pp. 252-263.

Blessing, Patricia. Rebuilding Anatolia after the Mongol Conquest: Islamic Architecture in the Lands of Rum, 1240-1330. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2014. (Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies; 17), p. 174.

Çayırdağ, M. Kayseri Tahrihi Araştirmalari. Kayseri, 2001, p. 35.

Cholet, Armand Pierre de. Voyage en Turquie dAsie. Paris, 1892, p. 67.

Eravşar, O. Anatolia-Syria Caravan Road and Menzil Caravanserais in the 13th century. ARAM, University of Oxford Oriental Institute, 2007.

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, p. 49, pp. 418-433.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961. Vol. 1, pp. 90-97, no. 27; vol. 3, pp. 142-147.

Erketlioğlu, Halit. Kayseri Kitabeleri. Kayseri, 2001, p. 48.

Gabriel, A. Monuments turcs d'Anatolie, I, II. Paris: Ed. De Boccard, 1931, 1934, pp. 93-98, pl. XXVIII, XXIX, XXX, fig 60-63.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 525.

Hillenbrand, R. (ed.). The Art of the Saljuqs in Iran and Anatolia. Proceedings of a Symposium held in Edinburgh in 1982, 1994, fig. 6.44, p. 552; 6.45, p. 349; plate 250, p. 347; plate 251, p. 348.

Jerphanion, G. de. Mélanges dArchéologie anatolienne. Mélanges de lUniversité Saint-Joseph, tome 13. Beirut, 1928, photo 1, fig. 4.

Karpuz, Haşim and Ahmet Kuş, Ibrahim Dıvarcı, I. and Feyzi Şimşek. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, vol. 1, pp. 473-474.

Kayseri Taşinmaz Kültür Varliklari Envanteri, vol. 2 (2009). Kayseri, p. 865-869.

Kinneir, J.M. Journey through Asia Minor, 1818, p. 562.

Mordtmann, A.D and Babinger, F. Anatolien: Skizzen und Reisebriefe aus Kleinasien, 1850-1859. Frankfurt, 1995.

Nahmer, Ernst von der. Vom Mittelmeer zum Pontus. Berlin, 1904, p. 195.

Osten, Hans Henning von der. Explorations in Hittite Asia Minor. Chicago: Oriental Institute Communications (8), 1929. P. 139, Fig. 143. (shows a picture of the Kiosk mosque and says it is One of the most beautiful and imposing Seljuk ruins in Anatolia.)

Özbek, Yıldıray. Tuzhisar Sultan Hanı, Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansarayları. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı, 2007 pp. 174-193 (includes bibliography).

Özergin M. K. Anadolu Selçklu Çağinda Anadolu Yollari [doctoral thesis] 1959, p. 79.

Özergin, M. Kemal. Anadoluda Selçuklu Kervansarayları, Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 162, n. 116.

Pergoletti, Francesco Balducci. La Pratica della Mercatura. ed. Allan Evans. Cambridge, MA., 1936, pp. 28-29.

Rice, Tamara Talbot. The Seljuks in Asia Minor, 1961, p. 206.

Sarre, F. and E. Herzfeld. Archeaologische Reise im Euphrat- und Tigris - Gebeit. Berlin, 1911-20.

Sümer, F. Yabunlu Pazari, an Important International Fair during the Saljuk Period. Istanbul, 1985, p. 91.

Tozer, H. F. Turkish Armenia and Eastern Asia Minor. London, 1881, p. 161.

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 418 photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 433; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 423; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

|

|

arch on western side of portal |

|

eastern courtyard cells |

Iwan of western courtyard cells

|

|

carving on the interior face of entry portal |

photo by John Ingham, 1961

|

|

restoration and original stonework of exterior facade |

arch on eastern side of portal |

|

|

|

|

kiosk mosque, seen from southwest |

detail of dragon heads at summit of mosque arches |

|

lion's head waterspout sculpture on side of western courtyard door

|

portal to covered section |

|

detail of arcs of iwan of western side |

detail of upper edge carving of courtyard walls

|

|

|

|

| photo taken in 1884 by J. H. Haynes during the Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor (Photographs of Asia Minor, #4776. Division of Rare Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library) | photo taken in 1884 by J. H. Haynes during the Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor (Photographs of Asia Minor, #4776. Division of Rare Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library) |

|

dome in covered section Photo by Erdmann (#144) |

detail of dome drum in covered section Photo by Erdmann (#143) |

|

naves on left side of covered section Photo by Erdmann (#146) |

detail of kiosk mosque decoration Photo by Semra Ögel in Erdmann (#153) |

|

mihrab of kiosk mosque Photo by Erdmann (#154) |

side niches on right side of entry portal Photo by Erdmann (#156)

|

|

courtyard kiosk mosque Photo by Erdmann (#152) |

central nave of covered section Photo by Erdmann (#142) |

|

door to covered section Photo by Erdmann (#147) |

stone bearing the name of the possible architect: "Master Yadigar fecit" transcription by Halit Erketlioğlu (Kayseri Kitabeleri, 2001, p. 48)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

for a series of photos of the han taken in 1961 and 1963 by John Ingham, click below:

The poet and historian Muhsin Ilyas Subaşi relates

the following anecdote relative to the Kayseri Sultan Han in his book on the

history of Kayseri (Dünden Bugüne Kayseri, Kayseri: Kivilcim Yayinevi,

2003; p. 92-94.) He has also written a poem to the han.

bellowed the Sultan to his Grand Vizier. And so in this way was the order

given to the Grand Vizier to oversee the construction of a series of caravansarais between the

larger cities of the kingdom, in order to ensure the safety and comfort of the

travelers on the roads in the lands under his charge.

One spring evening, the Sultan Alaeddin Keykubad gathered his viziers

together in his palace at Keykubadiyye. He explained to them the responsibilities

he expected of them concerning the services and operations of these hans.

|

SULTANHANI

MUHSİN İLYAS SUBAŞI

-to Katharine Branning

How many caravans have entered your doors with anticipation

How many voyagers have left their dreams in the heart of your courtyard

The stars kiss your forehead each night

What stories do the roads passing in front of you tell?

Homesickness and the melancholy of exile

Are loaded on the backs of your caravans each and every day of the year

The past and the future hide in the shadows of your monumental portal

Which welcomes and bids adieu to a thousand desires each day...

The Seljuks placed their very souls in your domes

Travelers have filled your halls with their trusting faith

So it was that your destiny grew,

But now, your visitors are none!

SULTANHANI

-Katharine Branning Hanımefendiye;

Kaç kervan umutla girer kapından,

Seyyahlar gönlünde hülyaya dalar.

Yıldızlar her gece öper alnından,

Ne söyler önünden geçen bu yollar?

Sıla özlemini, gurbet hüznünü,

Yüklenir sırtına yılın her günü,

Saklarken taç kapın yarını-dünü,

Her gün bin umutla boşalır, dolar

Selçuklu kubbene gönlünü koymuş,

Yolcular sofranda umuda doymuş,

Senin de kaderin demek ki buymuş,

Artık ne gelenin, ne gidenin var!..

MUHSİN İLYAS SUBAŞI

©2001-2025, Katharine Branning; All Rights Reserved.